EKI Energy Services, a prosaic-sounding firm in a niche corner of the energy market, was looking to raise just a couple of million dollars in its initial public offering on the Bombay Stock Exchange last year.

But soon after the IPO, the company's shares shot up 10,000 per cent, taking the valuation of the company from about $10 million to $1 billion.

By December, it was the year's best-performing stock in India's broadest index, making its founder a millionaire hundreds of times over.

That kind of moonshot market performance is rare but not entirely unheard of in India, particularly among small, thinly traded companies.

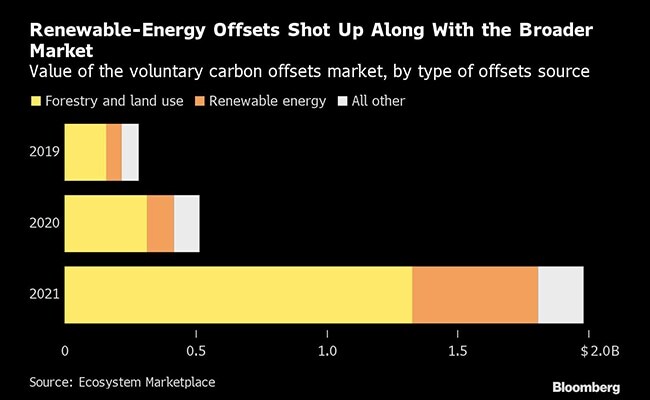

For EKI, there was something else at work. It's the first listed carbon offsets company, and the market price of those offsets — which comprise most of the firm's assets — was soaring.

Their value is now in question, and as doubt grows, EKI's shares have fallen 48 per cent from their peak. The worth of a carbon offset hinges on its usefulness in cutting worldwide emissions and not all are equally helpful.

On the lightly regulated voluntary carbon market, the majority, including most of those developed by EKI, may not help the fight against global warming at all.

These are offsets tied to renewable energy schemes — wind and solar farms, mostly — developed by well-resourced groups like the Adani Group in India, according to data compiled by the Berkeley Carbon Trading Project.

Renewable energy used to be a risky investment. Carbon offsets gave developers an extra revenue stream, designed to make the difference between an unattractive project and a profitable one.

In theory, the carbon payments were necessary to get more renewable energy into the mix, providing an additional environmental benefit.

But now renewable energy is in high demand. In most countries, projects can be profitable on their own, and the world's largest certification bodies — Verra and Gold Standard — only accept them from least-developed countries:

The credits aren't critical to financial viability, they're just icing on the cake. Most fail to meet the standard of “additionality,” according to a 2016 study for the European Commission, which means companies shouldn't be able to use them to cancel out their own pollution.

Absent that, there's no other reason to buy them.

“We are very bearish on renewable energy carbon credits,” said Kyle Harrison, a carbon markets analyst at BNEF, pointing out that they no longer get a seal of approval from the top independent verification bodies.

“They are still in high demand today, but in the coming years and the long term there's a big risk to buying or selling them.”

This has posed an existential challenge to EKI's business model, as well as the voluntary carbon markets and the companies that have been using these kinds of credits to make their net-zero claims.

Though EKI founder Manish Dabkara disagrees with most of the criticism, he conceded that his company must adjust.

It sees its salvation in a different kind of credit, tied to natural carbon sinks like mangrove forests. In 2021, EKI entered into a joint venture with Shell Plc to develop those kinds of “nature-based” projects in India, a tie-up worth $1.6 billion, according to local media reports.

“We are trying to get ourselves future-ready,” Dabkara said. “So that we'll not go out of our leadership role.”

Dabkara's background is in engineering and energy management. He founded EKI in 2008, offering energy audits and, eventually, consulting services.

At the time, the market for carbon offsets was much smaller. Dabkara didn't think it would stay that way, and EKI started building its inventory.

When demand spiked, the firm found it was sitting on a gold mine.

Today, EKI buys and sells credits and helps developers get their projects certified. After the IPO, the company opened an office in Turkey, boosted staff to more than 250 people, and added the World Bank and the Adani Group to a client list with over 3,000 names.

EKI has captured almost all business in India, Dabkara said. India generates more credits than the US and China, its closest competitors.

At the firm's headquarters in the city of Indore, Dabkara said that selling renewables credits doesn't necessarily amount to greenwashing.

Since the voluntary market has climbed in value, he said, critics and competitors have a financial incentive to tear down EKI, which also goes by the name Enking International.

“Different people have different ideologies,” he said in a lengthy interview, peppering his answers with data from PowerPoint slides. “In our industry, it is very, very tough, because there is no regulatory body nor any common consensus.”

Dabkara said developing countries like India have yet to decarbonize their power grids, meaning the firm's credits are still effective in the fight to lower emissions.

EKI used to register its wind projects with Verra, but since the standards tightened, EKI has found another organization, the three-year-old Global Carbon Council in Qatar, that has found a niche registering the projects the others won't.

“We need to demonstrate the additionality, why we need carbon credit revenue. In the case of renewable energy projects, it is very clear that we do prove financial additionality,” Dabkara said.

For now, EKI has no intention of abandoning renewables. Staff often travel to shrubby pockets of India to negotiate deals with developers and owners of wind or solar farms.

One of those projects is a wind farm near the town of Tonk Khurd, a few hours drive from EKI's headquarters.

On a recent visit, EKI employees donned hard hats, trudged through muddy bushes and climbed into the bowels of a mill to inspect the infrastructure.

It was built in 2016 by the Malpani Group, a Maharashtra conglomerate that also operates water parks, boarding schools and hotels.

Prafulla Khinvasara, who runs Malpani's renewables business, said the wind project has generated about 150,000 credits so far, and that they were always part of the plan to make the wind farm financially viable.

The wind farm was registered by Verra, but by today's standards, it wouldn't qualify, said Verra spokesperson Steven Zwick. “India is not a least-developed country, and the economics of renewable energy have changed,” he said.

How EKI manages this moment will ripple through the market for so-called voluntary offsets, which Morgan Stanley estimates could reach $35 billion by the end of the decade.

Of almost 500 million carbon credits supplied globally last year, EKI contributed around 90 million — most of them in renewables.

In Indore, a rebranding is afoot. The firm's logo no longer features a wind farm, opting instead for an abstract swirl of colors representing the earth, oceans and sky.

Giant photos of forests are silkscreened onto the walls of EKI's open-concept office.

The company has also started looking for other ways to shore up credits: A subsidiary of EKI recently opened a plant in the state of Maharashtra that can produce a few million energy-efficient cookstoves a year.

Despite those adjustments, a yo-yoing market for credits — and greater scrutiny over the integrity of what's being sold — has cast a cloud over EKI's business model.

Since the stock peaked in January, carbon credit prices have dropped, and the market now values EKI around 44 billion rupees ($542 million).

Dabkara and his family own nearly 75 per cent of the company. Next Orbit Ventures Fund and Maven India Fund hold about 9 per cent combined. Neither firm responded to requests to comment for this story.

The market for carbon offsets has also caught the attention of regulators and legislators.

While some carbon markets are regulated, like California's Compliance Offset Program or Alberta's Emission Offset System, the voluntary market is governed by no single authority.

Smaller and more freewheeling, it offers companies and others cheaper credits they can use to claim climate progress, with little scrutiny or oversight.

A Credit Suisse report recently described the voluntary market as a “wild west” filled with credits of “potentially questionable environmental integrity.”

Regulators are looking for a way in. A global securities watchdog raised concerns at COP27 about double counting of credits and lack of standardization for measuring emissions.

The US Securities and Exchange Commission recently proposed requiring companies to disclose information about carbon offsets if they are used to reach emissions goals.

“Now, investors are coming into the carbon credit market who are much more used to a financial services type model,” said Vaughan Lindsay, chief executive of global carbon credit consultancy Climate Impact Partners. “They want a model where there's a regulator over carbon credits as a commoditized item.”

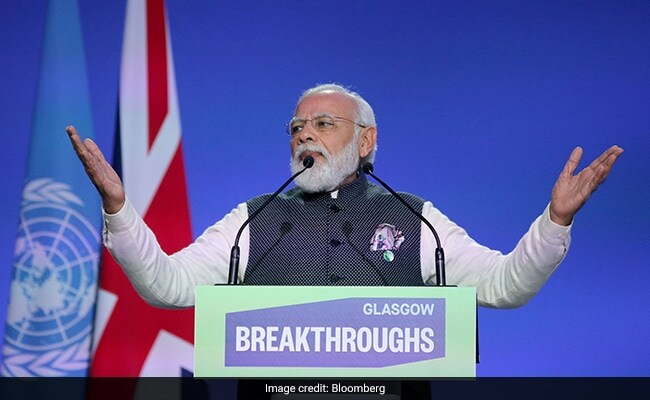

Governments may also have a vested interest. Prime Minister Narendra Modi is pushing a 2070 net-zero goal, and his Power Minister, Raj Kumar Singh, has said the country will limit exports of credits to prioritize its own climate goals, the Press Trust of India reported last month.

Only when India has the credits it needs can firms sell to customers abroad, he said.

As of now, increased regulation and new restrictions are purely hypothetical. For EKI and other, smaller firms in the business, the question is how quickly they can build up a stock of new credits and sell their existing inventory.

Nature-based projects require greater up-front investment of resources and India's environmental and zoning laws can be messy.

Many of EKI's projects will take around five years before they generate credits, the same time frame for its joint venture with Shell, which declined to comment for this story.

EKI is debt-light and has continued to expand into countries like Ghana, where renewables credits are less controversial.

Dabkara is confident that's plenty of time.

For many organizations, buying credits on the voluntary market is the easiest, cheapest way to meet their climate goals.

And as long as EKI can find an organization to certify its projects, the company can sell them. In his opinion, he said, “it's a win-win situation for everyone.”

(Except for the headline, this story has not been edited by NDTV staff and is published from a syndicated feed.)

Essential Business Intelligence, Continuous LIVE TV, Sharp Market Insights, Practical Personal Finance Advice and Latest Stories — On NDTV Profit.