Indian policymakers and politicians need a lesson or two in team building. No. Not the corporate HR kind of. I think sports movies are the best teachers. Let us take Shah Rukh Khan's Chak De! India as an example.

The players knew how to play hockey, but the team kept losing because the pieces did not move together. There was no coordination, no shared strategy, and no alignment between what each player did and what the team needed. If there is one sector that shows a lack of coordination, which hurts, it is soybeans. Well, we can find many examples in India, but for now, let us talk soybeans.

Understanding The Ecosystem

Farmers grow soybeans and sell them to crushers. They process the beans into oil and meal; the meal, which makes up about two-thirds of the bean, is sold to feed manufacturers for use in poultry, dairy, and aquaculture feeds. The demand for soy meal drives the industry due to its highest share. With an 18–20% share of the output, the soy oil is either sold to refiners or refined in-house. A small share of the bean gets consumed or turned into products like tofu, tempeh, soy chunks and ready-to-cook items.

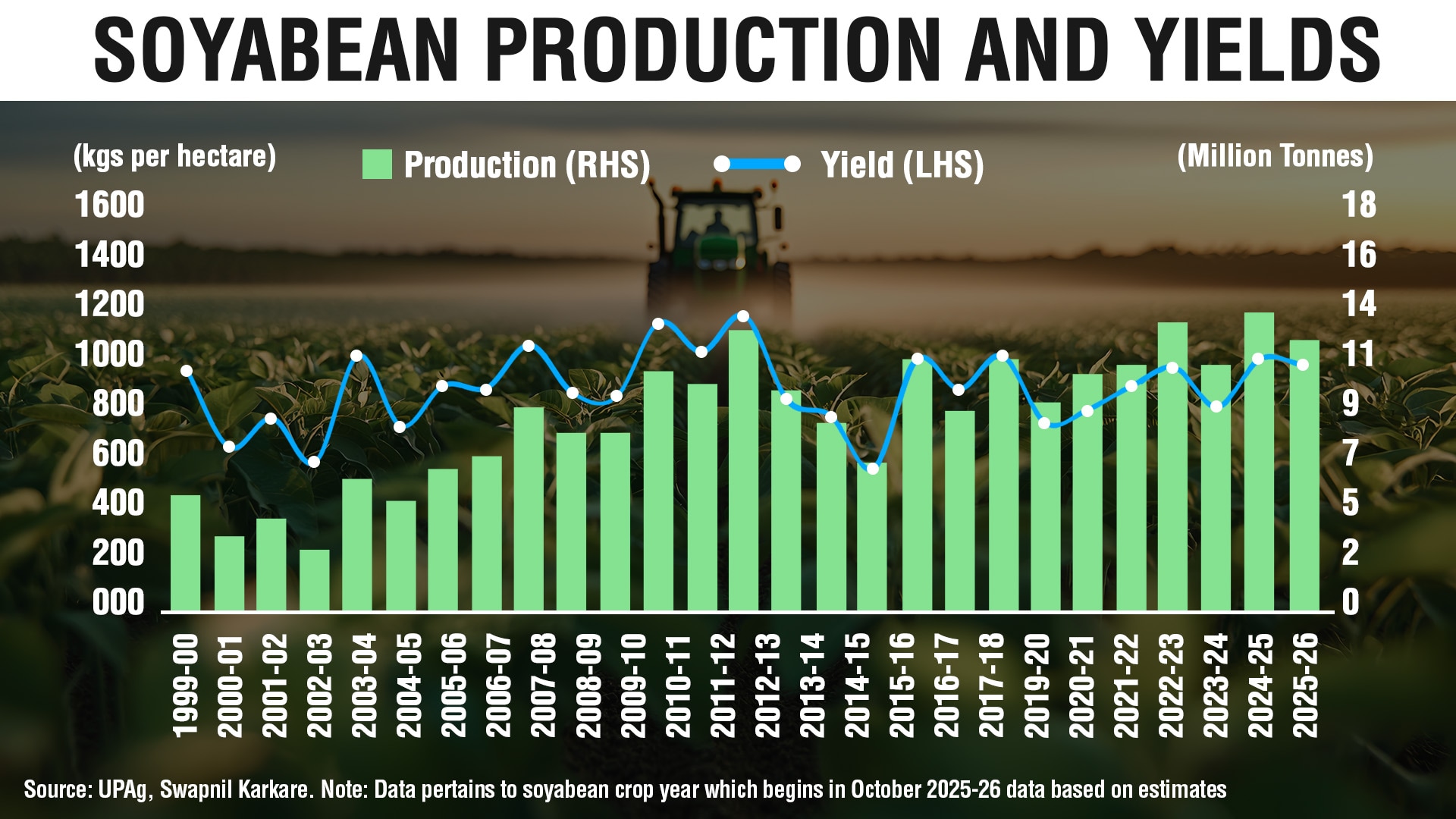

Globally, India ranks fifth in soybean production behind Brazil, the USA, Argentina, and China. India's production jumped sharply in the 2000s, rising from 5 million tonnes to nearly 15 million tonnes by 2012–13. But after that, it has plateaued, swinging between 12 and 15 million tonnes annually. Poor yields, limited acreage, and low oil recovery have kept soy meal and soy oil production stuck around 8-9 million tonnes and 1-2 million tonnes, respectively. Imports have filled the gap as demand increased.

A New Supplier In The Mix

We usually import soy oil from Argentina and Brazil. Together, they contribute to over half of the imports. But over the last few months, something unusual has happened. China has suddenly emerged as a major exporter of soy oil to India. Because China imported massive quantities of soybeans and produced more oil than it consumes, it has offloaded the surplus to other countries at deeper discounts. Exports in the first ten months of 2025 are nearly three times those of all of 2024.

Indian importers chose Chinese oil as it is $10–15 a tonne cheaper than South American oil and arrives within 10–12 days instead of 50–60. Experts say this trend may continue, as China has committed to buying substantial amounts of US soybeans under a trade deal through 2028. If China's economy slows, India could become its dumping ground, potentially making China the third-largest soy oil supplier to India.

Why Imports Are Rising Despite Low Domestic Prices?

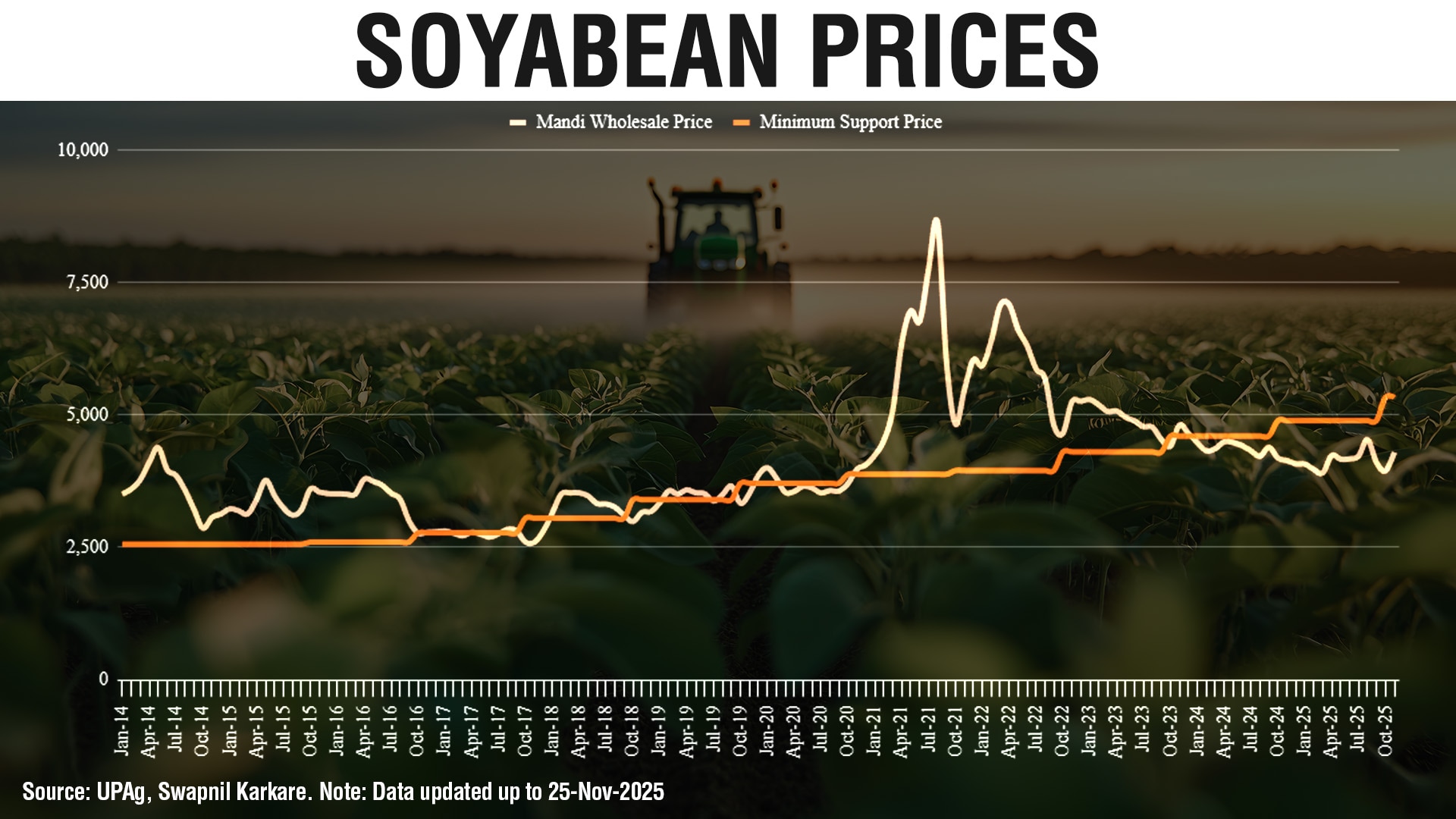

On paper, India should not be importing so much oil. Prices of soybeans in major producing regions of Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra and Rajasthan have remained lower than the minimum support price (MSP). Logically, cheaper soybeans should mean more crushing, more oil production, and lower imports. But the opposite is happening.

Feed makers have switched to a cheaper alternative to soy meal: DDGS (distillers' dried grains with solubles), a by-product of India's expanding ethanol industry that offers similar protein at a much lower cost. With soy meal demand falling, crushers have scaled back operations. Less crushing means less domestic oil and more imports.

Policies Are Made In Silos

The entire soyabean value chain: farmer → mandi → crusher → oil + meal → feed industry, is unaligned. India's policies have boosted soybean and ethanol production, but have failed to bring all pieces together. It shows that the policies on oilseeds, livestock feed, ethanol, and MSP don't speak to each other, just like the two forward position players from Chak De! India didn't pass the ball to each other. Each department has successfully delivered what it was asked to, but as a collective, we have failed.

Stepping Up The Ladder

Experience from Latin America shows what happens when countries remain as raw-material exporters. India cannot afford that trap; we must move up the ladder. India's IT industry shows how to achieve it. From a humble BPO industry, Indian IT has upgraded into a high-value Global Capability Centre (GCC). That's commendable.

Similarly, agriculture needs to be upgraded through boosting the food processing industry. For example, with abundant soybeans, we could become a global tofu producer and address protein deficiency at home. We must transform from a mere supplier of raw materials to the producer of high-value products. If we want to win the soybean game – or any farm or industrial game for that matter – we don't just need good players, we need a well-coordinated team.

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of NDTV Profit or its affiliates. Readers are advised to conduct their own research or consult a qualified professional before making any investment or business decisions. NDTV Profit does not guarantee the accuracy, completeness, or reliability of the information presented in this article.

Essential Business Intelligence, Continuous LIVE TV, Sharp Market Insights, Practical Personal Finance Advice and Latest Stories — On NDTV Profit.