About two years after the market regulator barred Ruchi Soya Ltd. for rigging castor seed futures, its lenders may recover only half their loans as India's largest edible oil maker is sold under the new bankruptcy law.

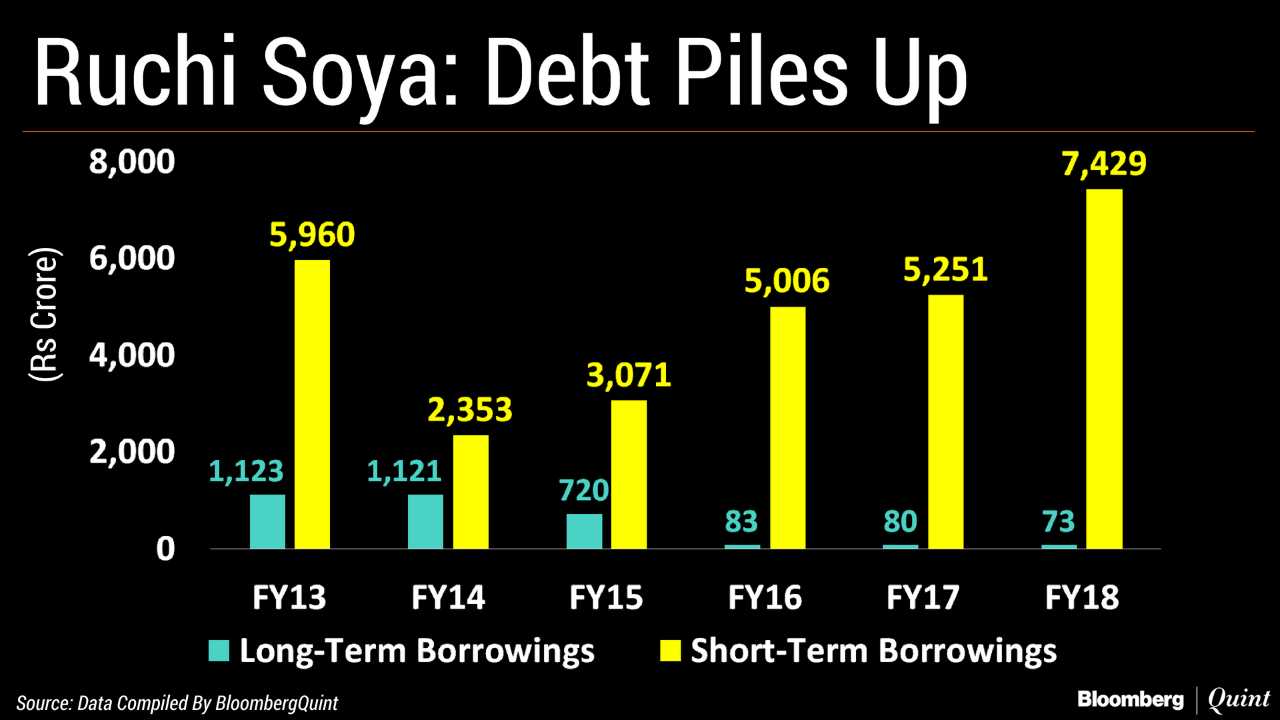

More than a financial loss, the ban was a tipping point for the company. Its troubles began much earlier in 2011. They stemmed from unfavourable duty structures for its largest edible oil refining business, and two successive below-average monsoons that hurt seed extraction—the second-biggest revenue contributor. Being a supplier to makers of refined oil to shampoos, the company had a long working capital cycle, leaving it short of cash. Short-term borrowings to tide over the crunch eventually left it under a pile of debt.

As it failed to repay more than Rs 9,000-crore loans, the central bank named Ruchi Soya in the second list of accounts identified for insolvency resolution under India's new bankruptcy law last year. Adani Wilmar Ltd., a Gautam Adani-group company, emerged the highest bidder with an offer of Rs 6,014 crore—Rs 4,300 crore to repay lenders led by State Bank of India and an equity infusion of Rs 1,714 crore, BloombergQuint reported earlier. That's a sixth of the peak market valuation of about Rs 36,000 crore of the edible oil maker.

Castor Seed Futures Manipulation

Ruchi Soya in 2015 bet on castor seeds as prices rose as high as Rs 5,000 a quintal. The company didn't hedge the exposure and a 40 percent crash after the new crop arrived and weak global demand left it with cash losses in the quarter ended March 2016. That led CARE Ratings to downgrade its bank facilities.

At the same time, it came under the Securities and Exchange Board of India's scanner for allegedly manipulating castor seed futures. The February 2016 contract for castor seed fell by 20 percent in January, and Ruchi Soya and its group entities allegedly had a large portion of the open interest, according to SEBI's probe, which forced the National Commodity and Derivatives Exchange to suspend trading in the commodity.

The SEBI investigation revealed that Ruchi Soya had transferred Rs 76.77 crore in January that year to at least five entities also holding significant positions in castor seed contracts. Finding Ruchi Soya guilty of market rigging, the regulator barred the company from the securities market.

The financial impact from its exposure to the contract wasn't big. But Ruchi Soya failed to recover from the setback as it came on the back of its mounting debt.

Duty Double Whammy

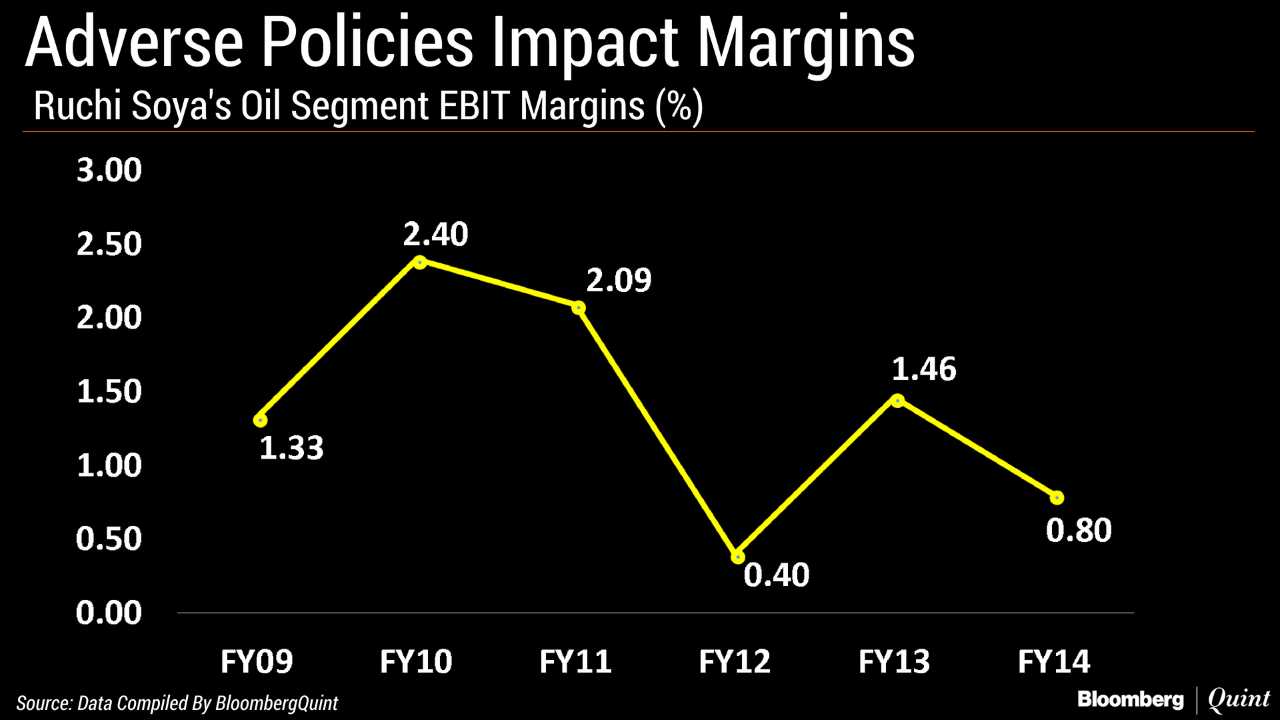

Ruchi Soya imports crude palm oil and sells the refined product that's used in everything from cooking oil to shampoos—a business that contributes more than 70 percent of its sales. Being an agro-processing company, it operates on thin margins. So, an unfavourable duty structure in domestic and international markets hurt the company even more.

Indonesia, the largest producer, in October 2011 made it cheaper to export the refined plam oil than the crude product. The South East Asian nation:

- Increased the export duty on crude palm oil by 150 basis points to 16.5 percent.

- Reduced the levy on refined bulk and consumer packed oil by 700 basis points to 8 percent and 800 basis to 2 percent, respectively. (100 basis points = one percentage point.)

In India, that increased the landed cost of crude palm oil imported from Indonesia and made refined oil cheaper. As a result, domestic refiners suffered in the second half of the financial year through March 2012.

The Indian government came to their rescue by increasing the import duty on refined oil to create a level-playing field in July 2012. But six months later, that benefit was largely undone. India increased the import duty on crude palm oil without raising the levy on refined oil—making the latter cheaper. That created cost pressures in a highly competitive domestic industry, Ruchi Soya had then said.

Historically, whenever Indonesia reduced export duties on refined palm oil, imports into India rose sharply as it was cheaper than importing crude palm oil and refining it, Hetal Gandhi, director at Crisil Research, told BloombergQuint. “Our industry interactions reveal low [Indonesian] export duties on refined palm oil impacted business models of Indian players who traded in refined oils, resulting in lower capacity utilisation.”

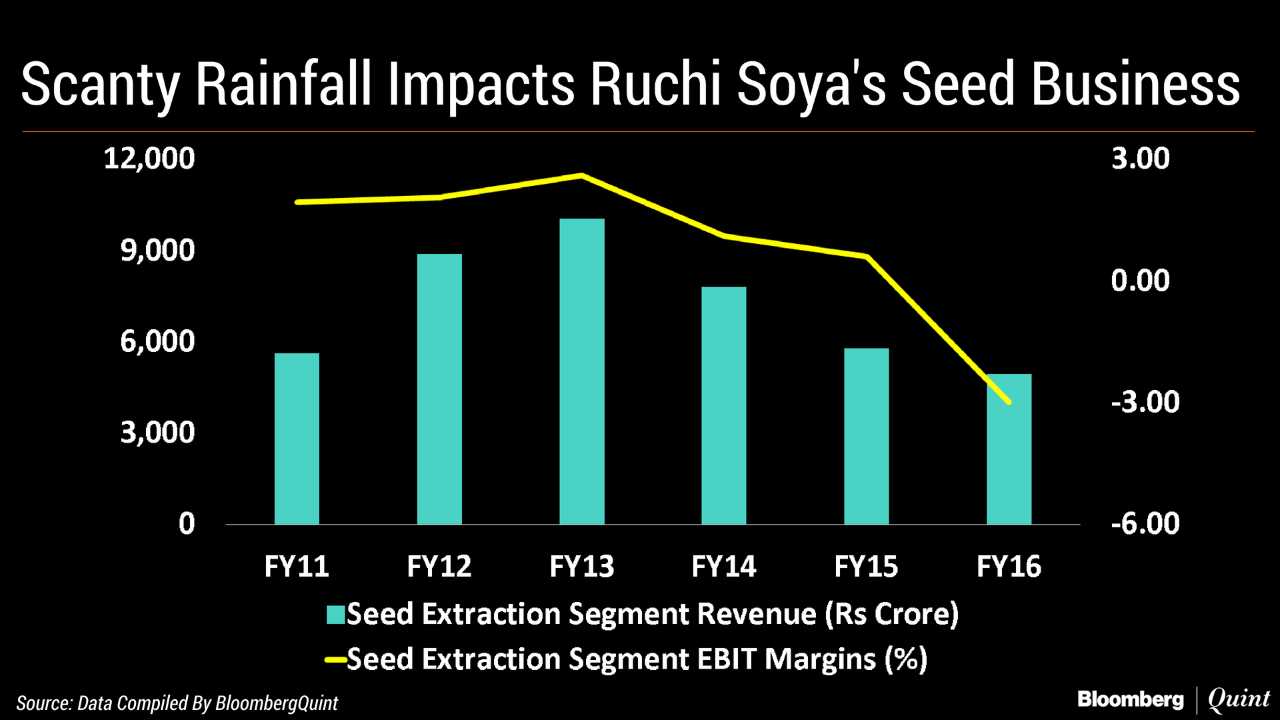

Unhelpful Rain Gods

India faced a drought-like situation with monsoon staying below normal in 2014 and 2015. Ruchi Soya's seed extraction business, which accounts for about 15 percent of its sales, bore the brunt as a rain shortfall destroyed crops and output fell. Adding to its woes, the production of its biggest seed export—soybean—remained healthy in overseas markets.

International prices of soybean declined because of healthy crop production in the U.S., Argentina and Brazil, Crisil's Gandhi said. “This coupled with low production of soybean crop owing to poor monsoons in India impacted competitiveness in the international market and consequently its exports.”

The Business Model

What made Ruchi Soya vulnerable to these changes was its business model. The company is a supplier to consumer goods makers and doesn't sell directly to consumers. That means payment period is relatively longer, elongating its working capital cycles. The company had to take on short-term debt to manage the shortfall.

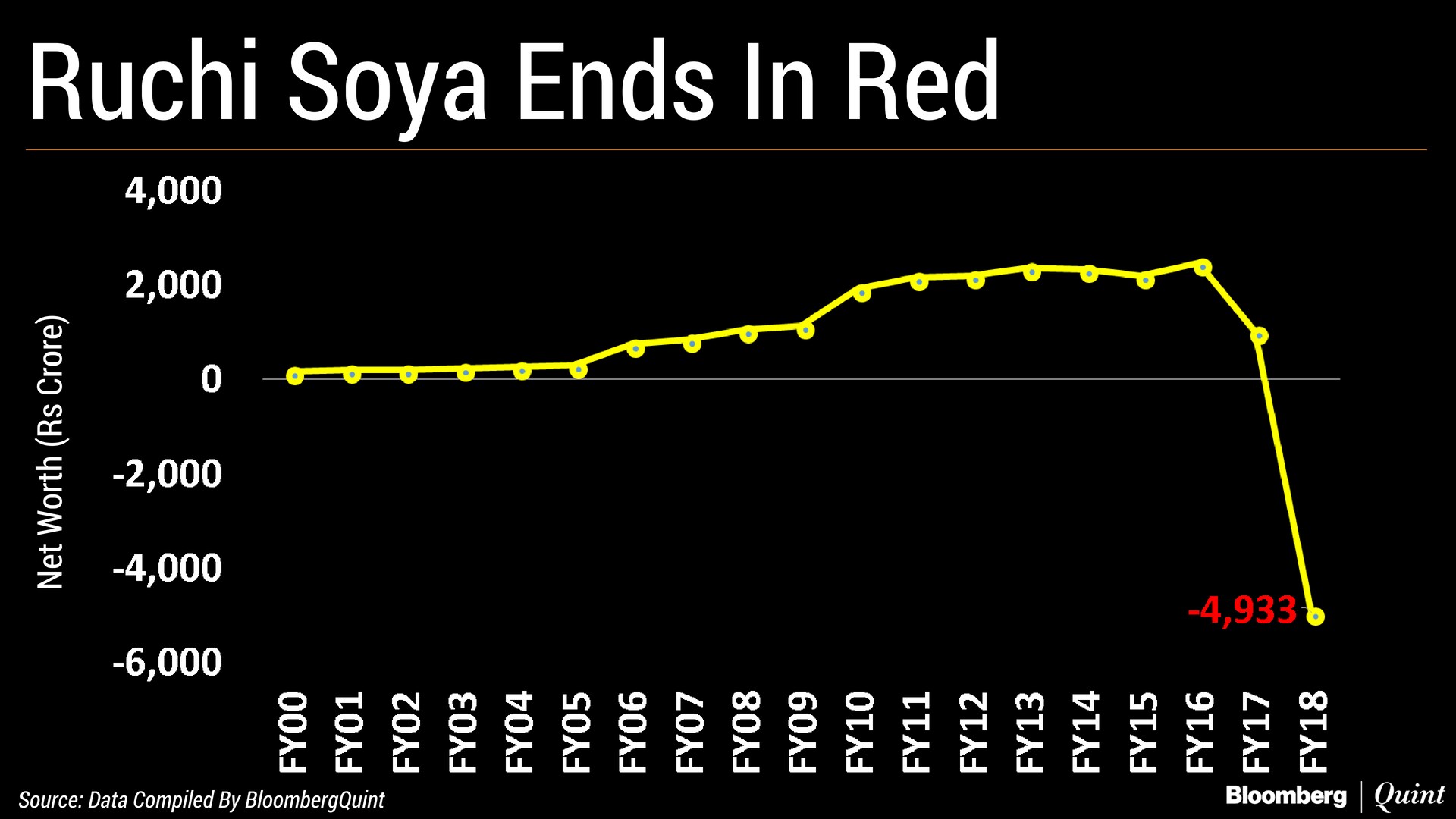

An increase in trade receivables days—a measure of how long invoices remain outstanding—in 2015 brought down cash flow from operations. Ruchi Soya fell into a continuous spiral of borrowing to pay outstanding short-term debt, Sameer Kalra, founder of Target Investing, told BloombergQuint. And the company eventually failed to pay debt as it couldn't recover its receivables. In the year ended March 2018, it wrote off close to Rs 5,000 crore worth of receivables. That turned the edible oil maker's net worth negative for the first time in 18 years.

After the Reserve Bank of India identified it among the largest bad loan cases, SBI-led lenders dragged the edible oil maker to the National Company Law Tribunal under the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code. Baba Ramdev-backed Patanjali Ayurved Ltd. and Adani Wilmar swooped in. While the Adani Group firm emerging as the highest bidder, Patanjali hasn't given up yet.

Kalra, whose clients may have an exposure to Ruchi Soya, still recommends a ‘Buy'. That's because he expects the successful bidder to shorten Ruchi Soya's working capital cycle—one of the biggest contributors to its downfall. Both Patanjali and Adani Wilmar are consumer-focused, he said.

Essential Business Intelligence, Continuous LIVE TV, Sharp Market Insights, Practical Personal Finance Advice and Latest Stories — On NDTV Profit.