In the coming years, coffee from Brazil might start to taste a bit different.

The South American country is the world's biggest producer of arabica, a mild variety of coffee bean. But as climate change makes it harder to grow those beans, some farmers are investing in robusta, which produces a more bitter bean but can tolerate higher temperatures and is more resistant to diseases.

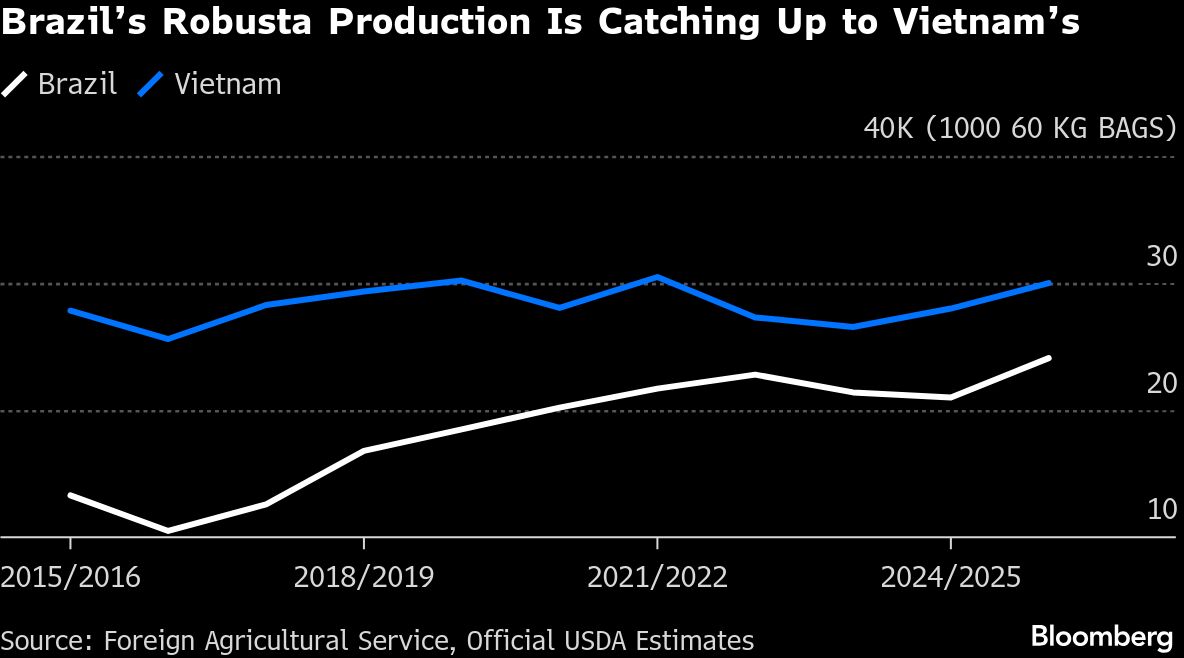

Brazil's traditional coffee growing regions, which largely produce arabica, have been beset by more intense and frequent droughts, and hotter temperatures. Arabica is still the country's main coffee export, but robusta production is now growing at a faster rate: by over 81% over the past 10 years, according to the United States Department of Agriculture, which tracks global coffee production.

For Brazil, robusta provides an opportunity to remain the world's largest coffee supplier in the future even as the effects of climate change intensify, says Fernando Maximiliano, Coffee Market Intelligence Manager at StoneX, a financial services company.

“It wasn't necessarily demand that resulted in the growth of robusta production,” he adds. “In reality, climate problems and losses in arabica were the main factors that contributed to stimulating robusta growth.”

For the past three years, arabica coffee production in Brazil has grown at a rate of around 2% to 2.5% annually, while robusta production has risen about 4.8% annually. This year's growing season, robusta hit a nearly 22% increase, a record harvest, according to StoneX. This means that robusta production has stood out for its ability to better cope with more adverse weather conditions and also for its profitability, analysts say.

In warmer areas of Brazil where arabica can't grow, coffee producers are finding ways to produce robusta and mitigate the impact of hotter temperatures. Planting coffee trees under the shade of native trees and other species is one of these techniques.

“This way it will remain productive, it will stay a little more moist, so it won't degrade so easily,” Jonatas Machado, commercial director of Café Apuí, an agroforestry robusta coffee producer in the Amazon region.

A different bean

Vietnam is the world's biggest robusta producer, but Brazil is catching up, and it could surpass the Southeast Asian country due to a well-structured supply chain, according to analysts at Rabobank, a financial services company.

Robusta has a higher caffeine concentration and a stronger taste than arabica. But younger generations pay less attention to the type of coffee they drink or its roast, and tend to prefer customized options, adding in things like milks, creamers and syrups, which hide the flavor of the beans.

“They're not so much about the origins, the tasting notes,” said Matthew Barry, global insight manager for food, cooking and meals at market research firm Euromonitor International.

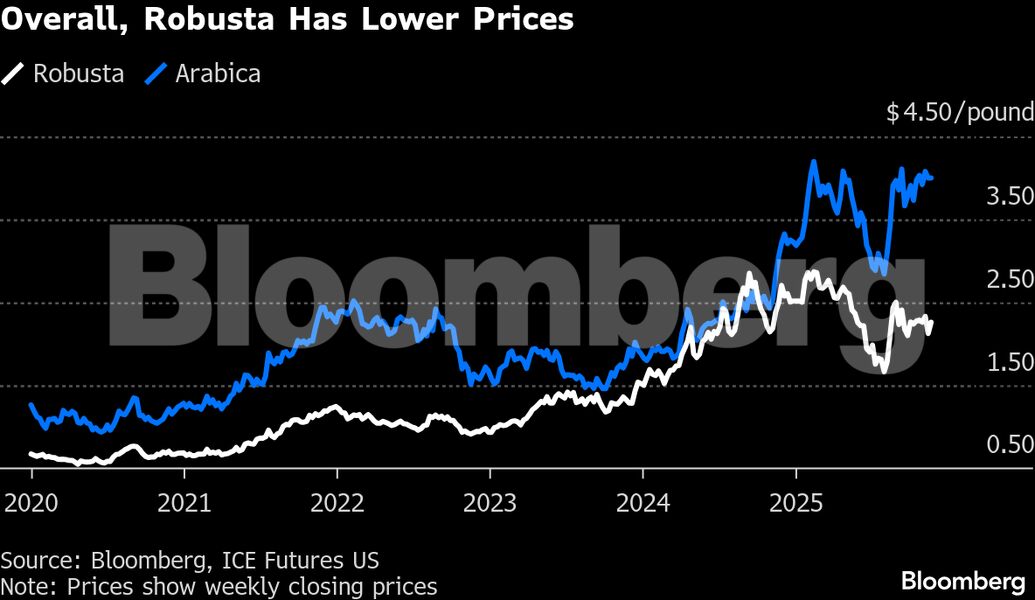

If coffee prices keep rising, consumers might also gravitate towards robusta, which costs less.

In Europe, the gap between robusta and arabica prices will likely be even wider in the coming years. A new law will require that imported commodities are certified to show they did not originate from recently deforested or degraded land, though its implementation date is still unclear. Instant coffee, which is mostly made with the robusta variety, is excluded from these rules. That carveout could increase the demand for robusta-based products, according to Rabobank.

The EU is the largest consumer of instant coffee, accounting for almost 50% of global revenue, according to Grand View Research, a business consulting firm.

While robusta tends to be cheaper than arabica, its prices have been reaching record highs.

These higher prices and the cultivars being almost twice as productive as arabica varietals have convinced a growing number of Brazilian coffee producers to invest in planting robusta, said Alexsandro Teixeira, coffee researcher at the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation.

Robusta producers are also improving the quality of their beans. That has made the varietal more attractive to consumers and led to an uptick in prices, he said.

Essential Business Intelligence, Continuous LIVE TV, Sharp Market Insights, Practical Personal Finance Advice and Latest Stories — On NDTV Profit.