(Bloomberg Opinion) -- In the new Cold War building between authoritarian states and democracies, petroleum appears to be the most potent weapon.

Russian President Vladimir Putin and Saudi Arabian Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman last week celebrated their recent output cuts, which have pushed up crude by 23% since the end of June. Costlier oil means more money for Moscow's war machine and Riyadh's construction boom, but higher gas prices for US consumers. Spying an opportunity to raise the salience of the yuan, China has meanwhile shifted almost all of its Russian crude imports into its own currency and pressed Riyadh to do the same.

The battle lines have been drawn, and President Joe Biden's climate-conscious administration threatens to be brought down by an alliance of oil-stained autocrats.

Not so fast. One of the risks of chemical weapons is that they can blow back on your own side, and it's no different when the chemical is a hydrocarbon molecule. Those thinking an oil-price war can operate as a smart bomb targeting open societies and sparing authoritarians might be surprised by the outcome.

That's because China — the biggest source of additional oil demand in recent decades, accounting for about three-quarters of marginal growth in 2023 — is at a crucial moment in its energy transition. Its gasoline demand will peak this year, according to China Petroleum & Chemical Corp., the massive state-controlled refiner known as Sinopec. Road fuel as a whole will follow next year, BloombergNEF forecasts.

Every dollar that Russia and Saudi Arabia add to the price of oil now will lead to a faster drop in long-term demand from their most important market, as well as the nation set to take its crude-consumption baton: India. Climate activists should be thanking Moscow and Riyadh. Exporters' misguided swagger will do as much to reduce the world's carbon footprint as a library-full of earnest ESG reports.

There's a simple rule of thumb to understand the short-term economic impact of oil supply shocks (the situation where producers cut output below consumers' demand levels, as we're seeing right now): exporters get richer, and importers get poorer. That's what happened in the 1973 Arab oil embargo and the 1979 Iranian revolution.

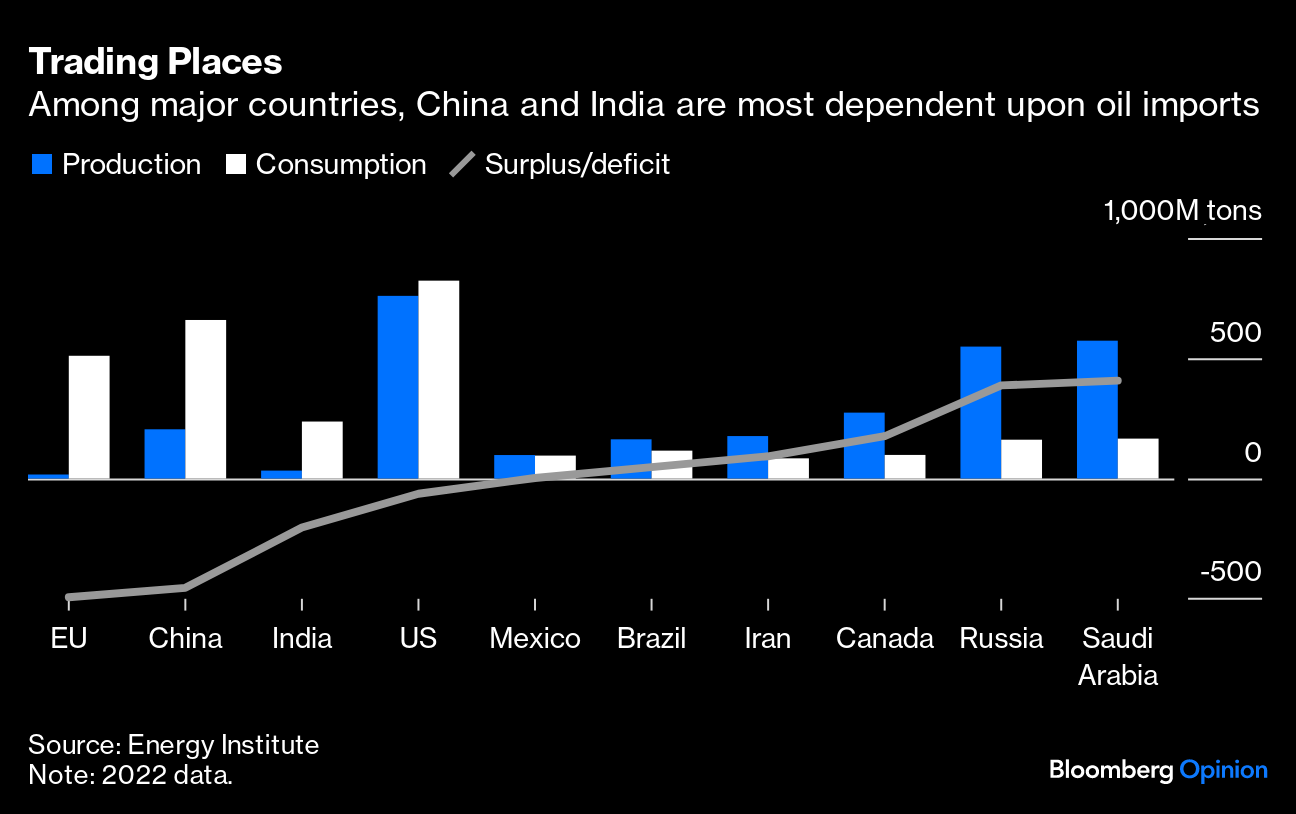

China overtook the US as the world's largest oil importer in 2017. Domestic wells now supply only about 30% of its needs, levels not much better than Europe's 22%(1). India, which both democratic and authoritarian blocs are keen to woo, is the second-largest net importer, and can supply only about 14% of its needs domestically. The US, on the other hand, has been a net exporter of petroleum for three years running.

Geological destiny means that strategic and climate considerations don't always work as you might expect. The US has struggled to cut oil demand because it's the world's biggest producer, a fact that risks blunting the decarbonization ambitions of its leaders. Meanwhile, China — whose coal-powered economy accounts for a third of the world's emissions — has been remarkably effective at reining in oil demand because rising oil imports hurt its energy security as well as its environment.

For China, this is a particularly bad moment to be applying leg-irons to growth. Its real estate industry, which comprises about 30% of the economy, is two years into a downturn that's cut prices by double-digit rates. Public debts are an estimated $23 trillion, about double the level relative to gross domestic product seen in the US on the eve of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. Attempts to stimulate the economy appear to be sputtering. Industrial profits have been running at their lowest level since the 2020 Covid-19 pandemic — something that's unlikely to be helped by higher prices for diesel and petrochemicals, key cost drivers for many businesses.

Meanwhile, sales of electric vehicles are booming. Seven out of the 10 best-selling cars in July came with a plug, and hit a 38% market share in August. Higher gasoline prices will only encourage more drivers to turn away from crude.

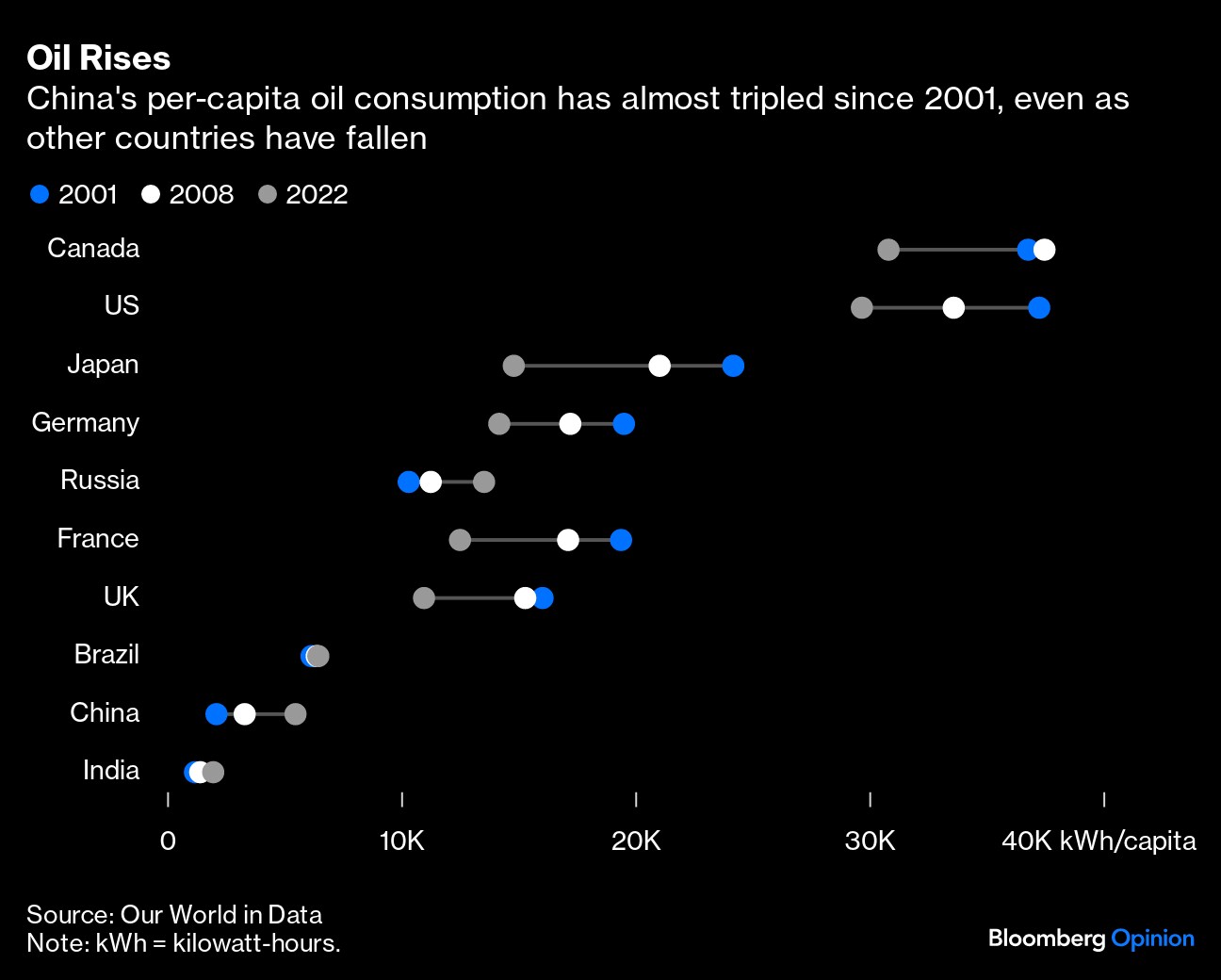

China does have a few strategic advantages over the US. Oil still comprises a smaller slice of energy demand than in developed countries, making price gains less of a burden on economic activity. That's changing, though — on a per-capita basis, China's consumption has nearly tripled since it joined the World Trade Organization in 2001, while many developed economies have seen the same measure fall by a third or more. It can buy Russian and Iranian crude at a discount, too, though prices will still rise in lockstep with the global benchmarks.

It also has a stockpile to fall back on. While Washington's Strategic Petroleum Reserve is running at its lowest levels since 1983 after the Biden administration's releases to stabilize the market in the wake of the Ukraine war, China's (whose actual volume is a closely-guarded secret) appears to be brimming at more than 1 billion barrels, about three times the size of the US inventory.

That won't be much comfort to exporters. If Beijing responds to higher prices by releasing barrels from its reserves, the effect will be to lower import demand and soften prices globally. That will dissipate the impact of Moscow and Riyadh's drive to force crude higher.

More From Bloomberg:

-

The ‘Peak Oil' Sequel Comes With a New Twist: John Authers

-

China Finds How to Lose Friends and Influence in Asia: Karishma Vaswani

-

How China's Downturn Could Save the World: David Fickling

(1) That's based on the continent, not the political entity. Exclude crude-rich Norway and the UK, and the European Union imports about 97% of its oil.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

David Fickling is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering energy and commodities. Previously, he worked for Bloomberg News, the Wall Street Journal and the Financial Times.

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com/opinion

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.

Essential Business Intelligence, Continuous LIVE TV, Sharp Market Insights, Practical Personal Finance Advice and Latest Stories — On NDTV Profit.