Just over a week ago, I valued Zomato ahead of its market debut, and as with almost every valuation that I do on this forum, I heard from many of you. Some of you felt that I was being far too generous in my assumptions about market share and profitability, for a company with no history of making money, and that I was overvaluing the company. Many others argued that I was understating the growth in the Indian food market and the company's potential to enter new markets, and thus undervaluing the company, a point that the market made even more emphatically by pricing the stock at about three times my estimated value. A few of you posited that I was missing the point entirely, and that Zomato is a trader's game, and that there are plenty of reasons for traders to be optimistic about its future prospects. In this article, rather than impose my story (and value) on you, I offer a template for telling your own story about Zomato, and arriving at your own estimate of value.

The Prelude

After I posted my valuation last week, I did find some of the portrayals of my article to be a little unsettling. Some started by describing me as some kind of valuation luminary, and then proceeding to describe what I did to arrive at value as the result of deeply insightful research. Let me dispel both delusions. First, there is nothing in valuation that merits the use of “expert” or “guru” as a descriptor, since it is for the most part, common sense, layered with a few valuation basics. Second, while valuation practitioners have created their own buzzwords to create an aura of mystery, and added complexities, often with no reason other than to intimidate outsiders, I believe that anyone should be able to value a company, as I hope to show later in this article. There was also some who misread my article to imply that I disliked Zomato as a company, or that I was trying to talk others out of investing in the company. Neither assertion is true, and since they relate to what I view as fundamental truths about investing, let me elaborate:

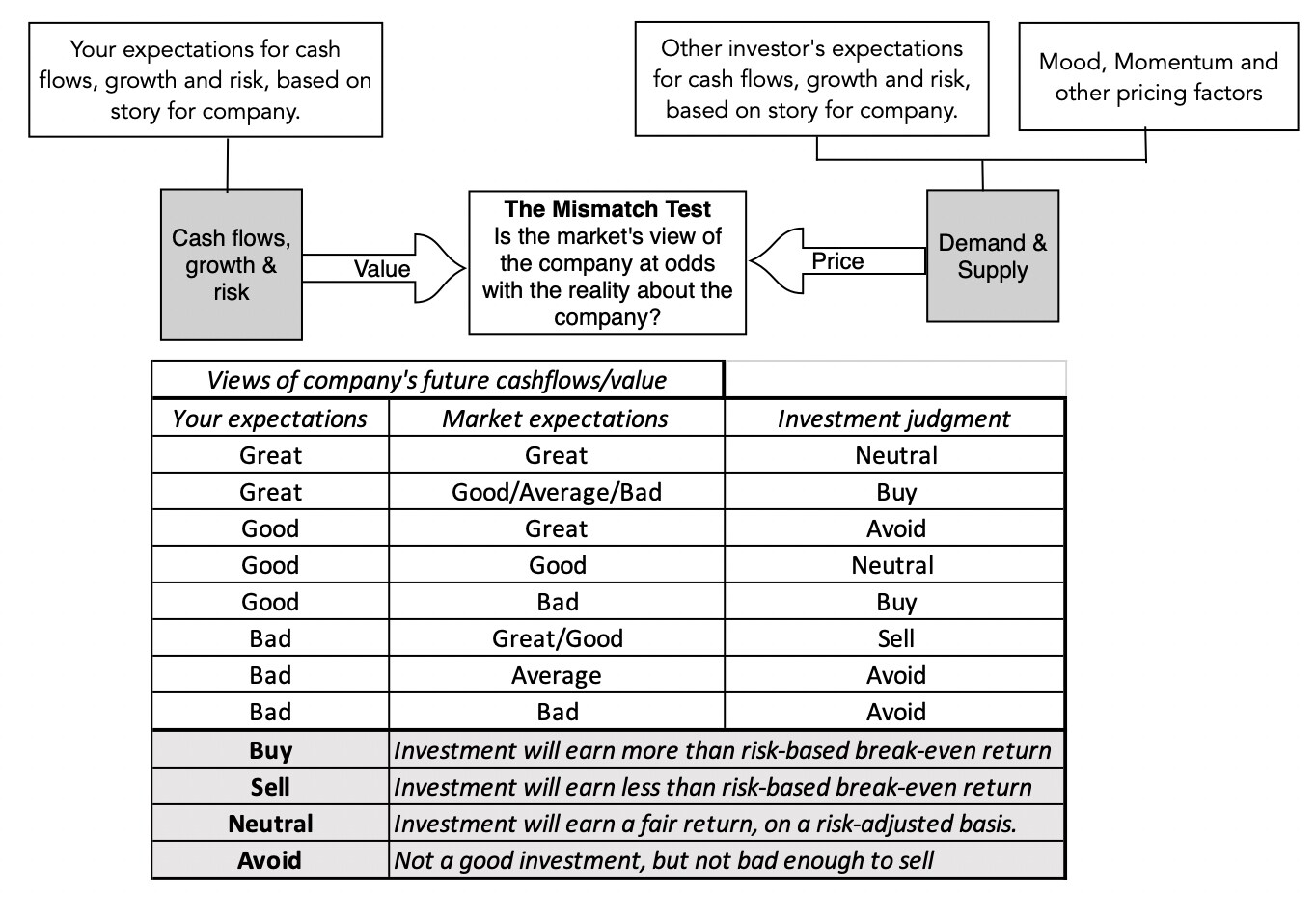

1. Good Company versus Good Investment: While it is true that, at least in my assessment, Zomato is overpriced, making it a bad investment, it does not follow that it is a bad company. I have written about the contrast between good investments and good companies before, but the picture below captures the essence:

In short, your assessment of whether a company is good, average or bad is based upon how you see their business model playing out in future earnings and cash flows, but your assessment of whether it is a good investment depends upon whether your expectations for the company are more positive or negative than the market expectations for that company. My story for Zomato is a very positive one, where the company not only maintains its market share of a growing Indian market, but preserves its profitability, in the face of competition. That is one reason that I emphasized that unlike some, who have concluded that its money-losing status and big ambitions make it a "bad" company, my conclusion is that it is a good company. That said, the market seems to be pricing in the expectation that it will be a great company, and in my view, that judgment is premature.

2. Taking ownership of investment decisions: I value companies for an audience of one, and that audience member is forgiving and understanding, because I see him in the mirror every day. It has always been my belief that as investors, each of us needs to take ownership of our investment decisions, and that buying or selling a company because someone else is doing so, even if that person has legendary investment credentials, is a dereliction of investment due diligence. Thus, if you find Zomato to be cheap and buy it, I have no desire to talk you out of your decision, since it is your money that you are investing, and that decision should be based upon your assessment of the company's prospects, not mine.

If investing is all about market price and how it relates to your assessment of value, it follows that there will never be consensus, and that disagreement is not only part and parcel of the process, but a healthy component in good valuation.

Valuation Storytelling: The Feedback Loop

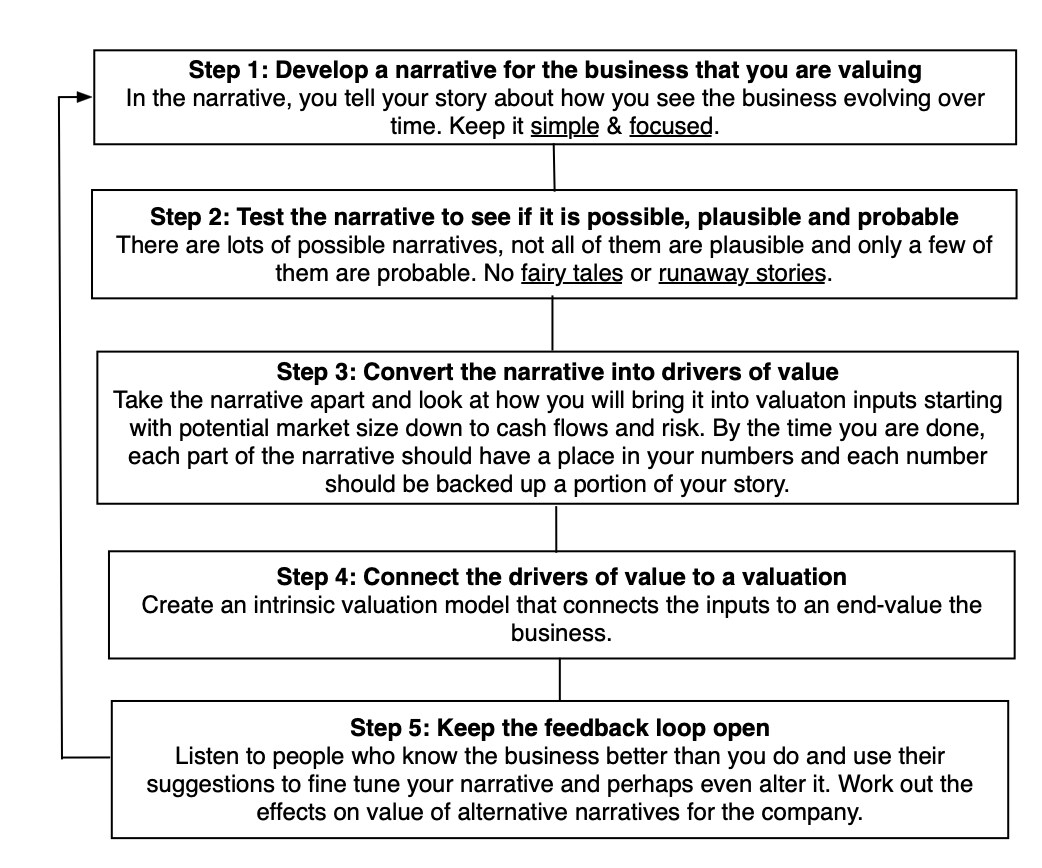

In my valuation of Zomato, I laid out the story that I was telling about the company and how it played out in valuation numbers. It is part of a broader theme that I have harped on for years, which is that a good valuation is a bridge between story and numbers, and in my book on how to build that bridge, I talked about a five-step process:

In my last article on Zomato, you saw much of this process play out, but I want to focus on the fifth step, i.e., keeping the feedback loop open, and what it requires:

1. Talk to a diverse audience: We live in a world of specialization, in almost every aspect of life, and that trend comes with mixed blessings. On the plus side, we now have experts who have spent their entire lives delving into an extraordinarily narrow slice of a discipline, often at the expense of the rest of that discipline. On the minus side, this expertise creates tunnel vision, where these experts often lose the forest for the trees. To make things worse, we have created workplaces, where these specialists often interact only with each other, making their isolation almost complete. I am lucky that I am able to interact with people with very different backgrounds (bankers, VCs, founders, CFOs, regulators), from different geographies and with very different perspectives, through my teaching and writing, and my suggestion is that you hang out less with people who think just like you do (often because they have the same training and credentials) and more with people who do not.

2. Transparency over opacity: You have all heard the old saying about economists (and market gurus) needing three hands, because they constantly seem to have two of them busy, with their "on the one hand, and the other" prevarications about the future, that leave listeners confused about what they are predicting. I start with my valuation classes with the motto that I would rather be transparently wrong than opaquely right. Consequently, when I value companies, I try to take a stand on value, and be open about process, data and mechanics, so that anyone can not only replicate what I did, but also find their own points of disagreement, and reflect those changes in their own assessed values. I am also well aware of the risk that by putting out valuation details, I will be proven wrong in the future, but I like the accountability that comes with disclosure. In commenting on my Zomato valuation, some of you pointed to how wrong I have been in valuing Uber and Tesla in the past, and while that is fair game, I have made peace (really) with my mistakes.

3. Listen to those who disagree with you: I try to listen to those who disagree with me on any forum, whether it be social media or snail mail, for a very selfish reason. On every company that I value, I know that there are people out there who know more than I do about some aspect of the company (its products, market or competition) that I am valuing, and I can learn from them. With Zomato, for instance, I have learned about online food delivery and restaurants in India in the two weeks since I posted my Zomato valuation. I have some understanding of why Zomato Pro has not caught on as quickly as the company thought it would, why some of you prefer Swiggy, and even what you like to order from restaurants. (Biryani seems to a much bigger draw, for Indian diners, than it was in the days that I was growing up in India.)

4. Be willing to change: The three most freeing words in investing and valuation are “I was wrong”, and I would be lying if I said they comes easily to me. That said, I find it easier to say those words now that I have had practice, and while some view this as an admission of weakness, saying it releases you to tell a better, and sometimes different, story. Bill Gurley's critique of my narrow definitions of total market in my first Uber valuation significantly changed not only my valuation of that company, but has played a role in how I estimate total market size and value sharing economy companies.

The feedback that I have received on Zomato has already had tangible effects on my valuation. For instance, some of you noted that the corporate tax rate in India is 25%, not 30%, and while the Indian tax code with its predilection to add in surcharges that seem to last forever, and exceptions, still leaves me confused, I will concede on this point (pushing up my value per share marginally from Rs 41/share to about Rs 43/share). I have had pushback on my story's focus on Indian food delivery, with some pointing to the potential for Zomato to expand its market globally, and others to the expansion possibilities in Indian grocery deliveries and from cloud kitchens. While I believe that the networking advantage that works to Zomato's benefits will stymie them if they try to expand to large foreign markets and that the grocery delivery market, at least for the moment, offers too small a slice of revenues to be a game-changer for the company, those are legitimate points.

A DIY Valuation Of Zomato

If, as you read my Zomato valuation, you found yourself disagreeing with me, I would like to offer you a way of valuing the company, with your disagreements incorporated into the value. Put simply, I will take care of the background work and the valuation mechanics, if you can supply the story. So, if you are ready, let's go!

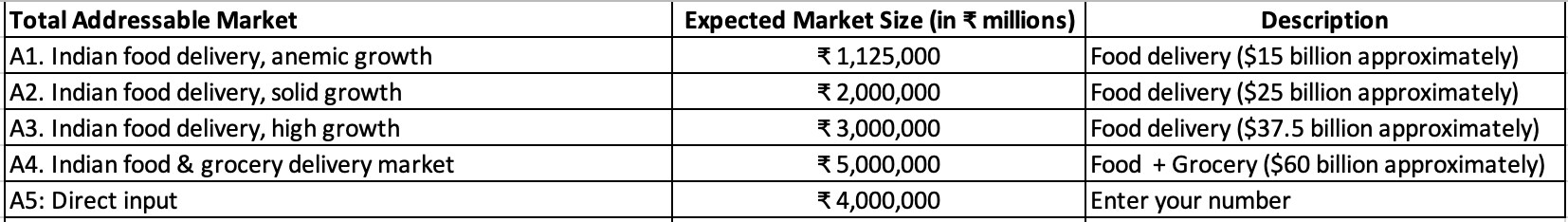

1. Total Addressable Market And Scaling Growth

The first and biggest part of the Zomato story is the total market that it can go after, since it defines how big a story you can tell, and by extension, how big your value can be. In my valuation, I assumed that Zomato's primary revenues would continue to come from customers ordering food from restaurants for pickup and delivery, and that notwithstanding its global ambitions, India will remain its main market. That assumption led to my base case estimate of about Rs 2,00,000 lakh crore (just over $25 billion) for the total market. This was the assumption that got the most pushback, on two fronts, first that I was ignoring the possibility that Zomato's global reach could expand that market and second that adding grocery deliveries could make the market bigger. Some also mentioned the potential for growth from cloud kitchens, i.e., restaurants (small and large) that offer food only for delivery. So, with no further ado, here are your choices:

For pessimists about Indian growth and eating habits, I offer the possibility that the total market will grow to only Rs 1,12,500 crore ($15 billion) in ten years. For optimists, allowing for more growth in the Indian market or adding global growth makes the market bigger, and adding grocery deliveries to the total market more than doubles the market. In addition, you can make a judgment on whether the growth will be front ended (more growth in the early years) or spread evenly over time:

This choice will be tied to how quickly you think that the Indian economy and food delivery market will develop over time.

2. Market Share

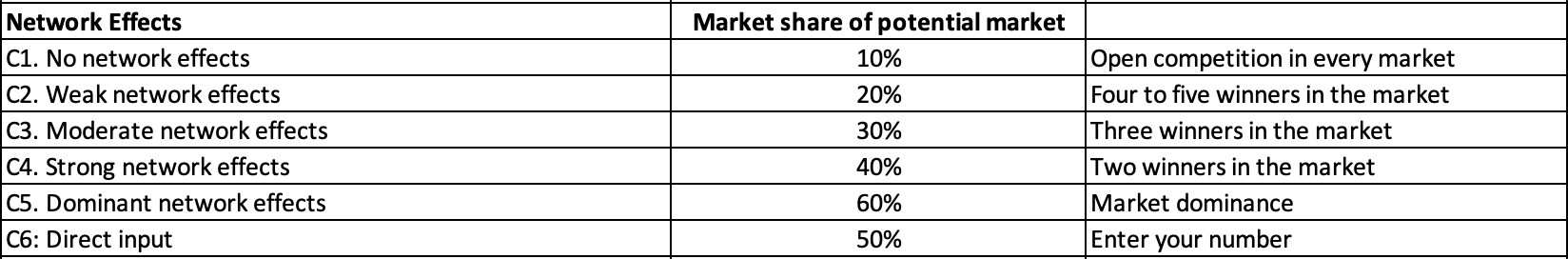

Zomato is currently one of the two largest companies in the Indian food delivery market, with a market share that is just above the the 40%. In my valuation, I assume that the food delivery market, following a pattern that seems to be forming globally, will remain dominated by a couple of players, and leave the market share at 40%. Many of you suggested that the Indian market's diversity, across regions and income classes, would result in a more splintered market, with lower market share, but a few argued that Zomato's capital raise would allow it to dominate the market, earning an even higher market share:

In making this judgment, keep in mind that the more expansively you define the total market, the more you may have to pull back on market share. Also, if you do choose a dominant market share (60% or higher), consider the potential for legal and regulatory pushback.

3. Revenue Slice

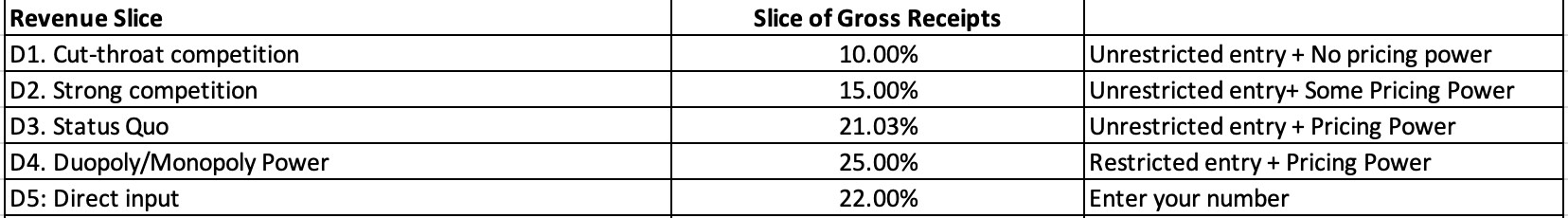

The driver for the online food delivery business remains the slice of the total food order that accrues to them as base revenues, and this slice is what has to use to pay delivery personnel, cover operating costs and be used to acquire new customers. In my base case valuation, I assumed that Zomato would get to keep the 22% of gross order value in the future, a little higher than its Covid-affected FY 2021 numbers and a little lower than its FY2020 numbers. As Zomato tries to maintain its leading market share of the Indian market, this number will be the one that will come under the most pressure, since an aggressive competitor (like Amazon Food) may be willing to settle for a lower percentage. Note that there is also the possibility that the Indian food delivery market will end up dominated by two or three companies, and that these companies could come to an implicit agreement to leave the GOV slice untouched. That would be unfair to restaurants, but will improve the bottom line for the online delivery companies:

In making a choice on revenue slice, recognize that it will be affected by your choices on market size and market share. Thus, if your total market is much bigger, because you have added in grocery deliveries, you should also be using a lower revenue slice, since grocery stores, with their lower profit margins, are reluctant to let delivery companies keep more than 10% of the order. In the US, for instance, large grocers have pushed back against Instacart's cut (about 9%) of gross order value, and have started their own delivery services.

4. Operating Margins And Pathway to Profitability

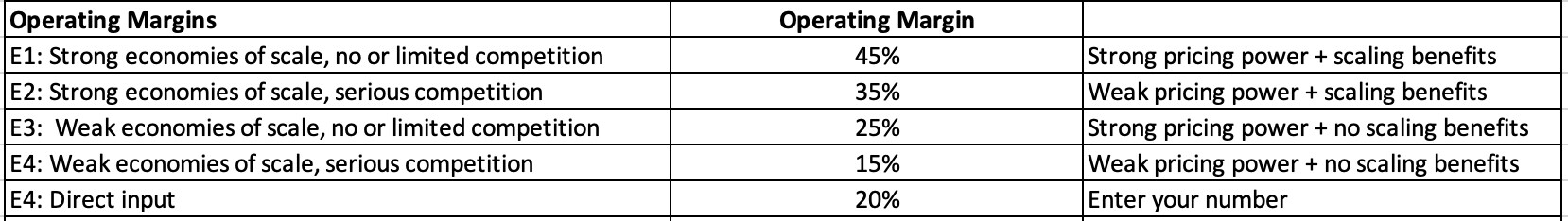

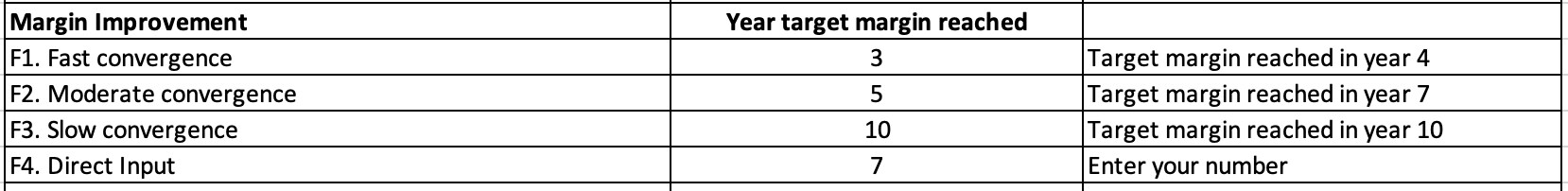

In my valuation of Zomato, I noted that one of the advantages of being an intermediary is that the gross and operating margins tend to be high, once growth subsides that the expenses (selling and advertising costs) associated with delivering that growth scale down. In my base case, I assumed a pre-tax target operating margin of 35%, but that margin will depend on how the competitive landscape evolves. If you have only two or three players, with a live-and-let-live attitude, margins will be high for all of the competitors, but if they continue to try to aggressively claw back from market share, through advertising and discounting, they will decline for all of the players.

In my Zomato valuation, I also assumed that the company would continue to lose money in the near term, but that operating margins would converge on the target value in year 7. This assumption implicitly stands in for your views on how smooth the pathway to profitability will be for Zomato, with rockier pathways leading to a longer time period before you reach the target margin:

Here again, the assumptions about margins will depend on the businesses that you believe that Zomato can enter, using its platform capabilities. In the last week, I have heard arguments that Zomato can go beyond food delivery into running cloud kitchens, enter the health/fitness market and even be a lender to restaurants. While all of these are possible, these are businesses with very different profitability profiles, and are unlikely to earn operating margins even remotely close to the margins that can be earned in the online food delivery business.

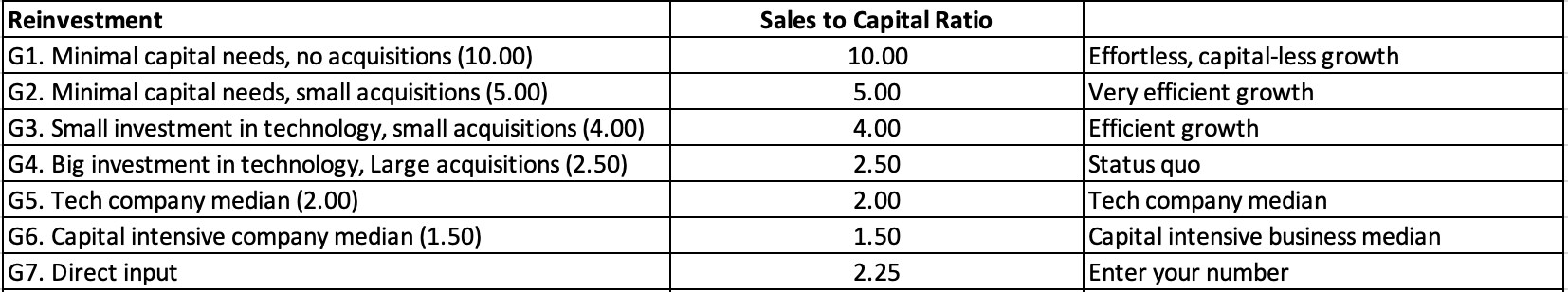

5. Reinvestment

The key ingredient connecting value to growth is the reinvestment needed to sustain that growth. Put simply, a company that has to reinvest large amounts to deliver a specific growth rate will have lower cash flows and be worth less than an another company with the same growth rate, but lower reinvestment needs. The input that I used in the Zomato valuation to bring in reinvestment is the sales to capital ratio, a metric measuring how much revenue is generated for each dollar of capital invested, with reinvestment defined broadly to include net capital expenditures (capital expenditures minus depreciation), working capital needs, technology investments in the platform and acquisitions, with a higher number reflecting more efficient reinvestment. In my story, I see a continuation of their historical pattern of reinvesting in acquisitions and technology, albeit with more efficient growth in the near term, as the company bounces back from the C effect; my sales to capital ratio for next year is 5.00, dropping to 3.00 in years 2-5, before settling into 2.50 in steady state. Here again, there is room for debate, since you could argue for less reinvestment in the future (than I am assuming), based upon past acquisitions paying off, or for more reinvestment, if the company tries to buy its way into new markets and businesses.

Since the sales to capital ratio is not one that is widely reported, you may find yourself lacking perspective on what comprises a high, low or typical number.

6. Risk

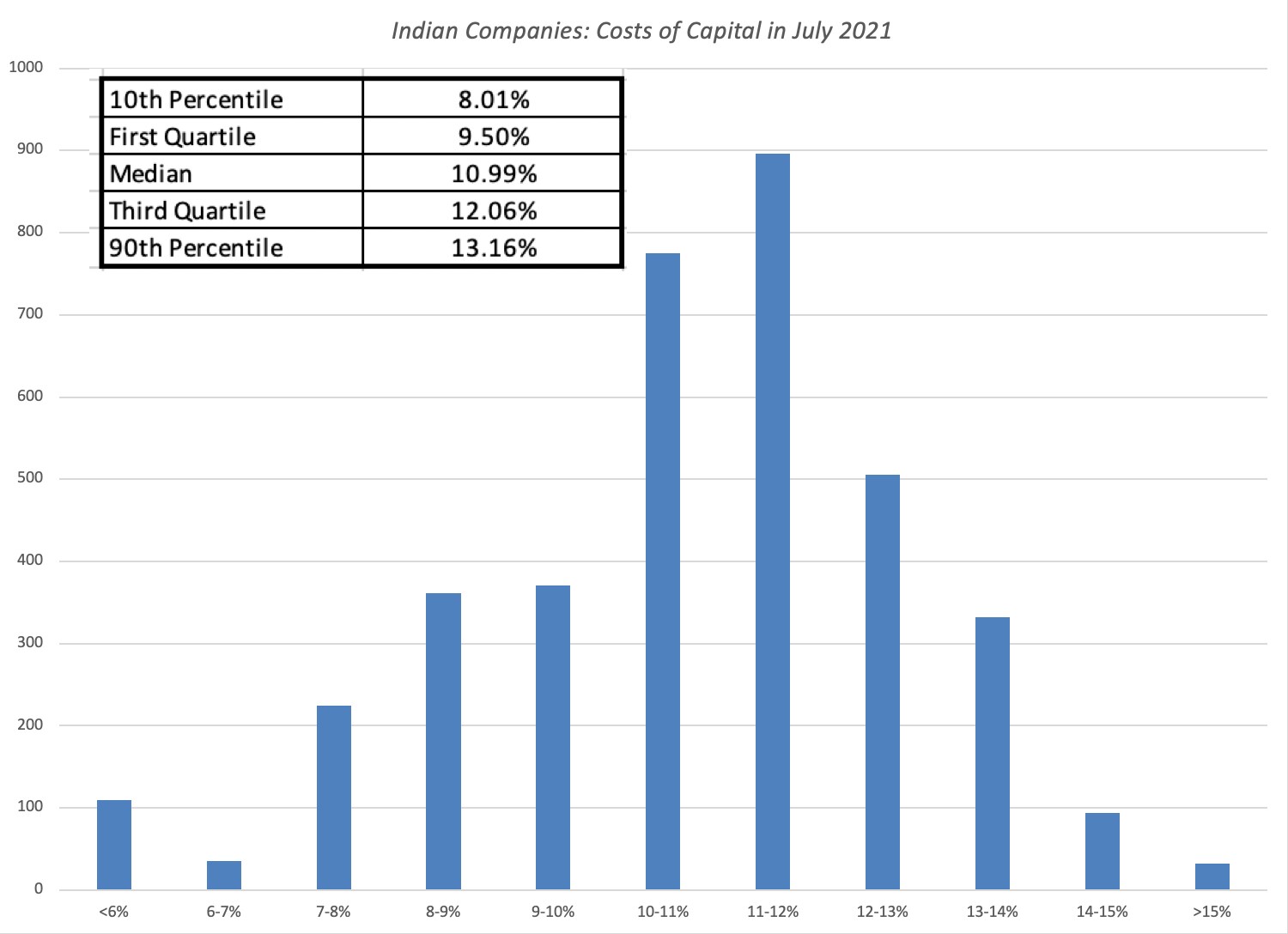

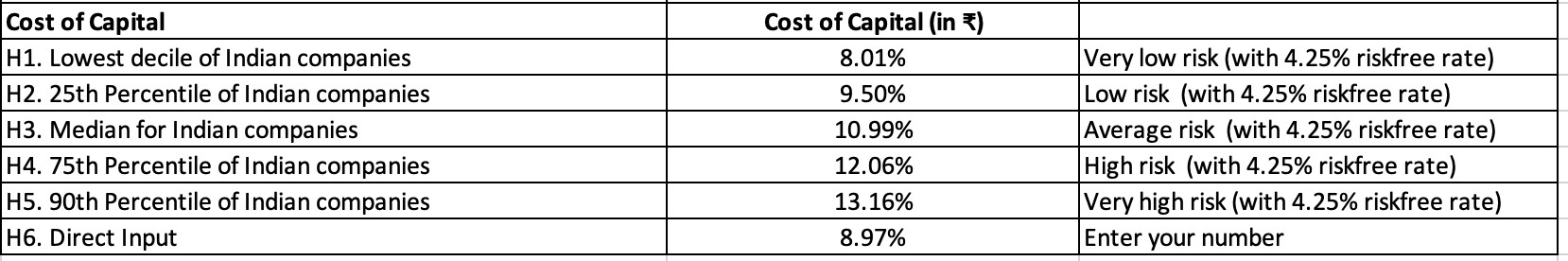

There are two risk parameters in intrinsic valuation, the cost of capital accounting for the risk or variability in expected cash flows and the failure probability incorporating the risk that your company will not make it as a going concern. In the Zomato valuation, I attached a 10% chance of failure, with the large cash balance (especially after the IPO) offsetting concerns from the company's money losing, cash burning status. For the cost of capital, I followed the traditional route of estimating the company's costs of equity (based upon its exposure to market risk) and after-tax cost of debt, to arrive at an initial cost of capital of 10.25%, which I lowered over time to 8.97%, with both numbers in Indian rupees. For those of you who may disagree with my estimates on these numbers, I will make the confession that in this valuation, this input is not on my top ten list of key inputs. To see why, consider this histogram of costs of capital (that I computed) for publicly traded Indian companies in July 2021:

Note that 80% of Indian companies have costs of capital between 8.01% and 13.16%, and that half have costs of capital between 9.50% and 12.06%. To estimate a cost of capital for Zomato, consider this simplistic (but effective) approach, based on these estimates:

Thus, if you feel that I have underestimated Zomato's risk in my valuation, consider going with an initial cost of capital of 12.06% (the third quartile), whereas if you believe that I have overestimated the risk, go with 9.50% (the first quartile). Then, move on to the inputs that really matter, since, in my view, this is not one of them.

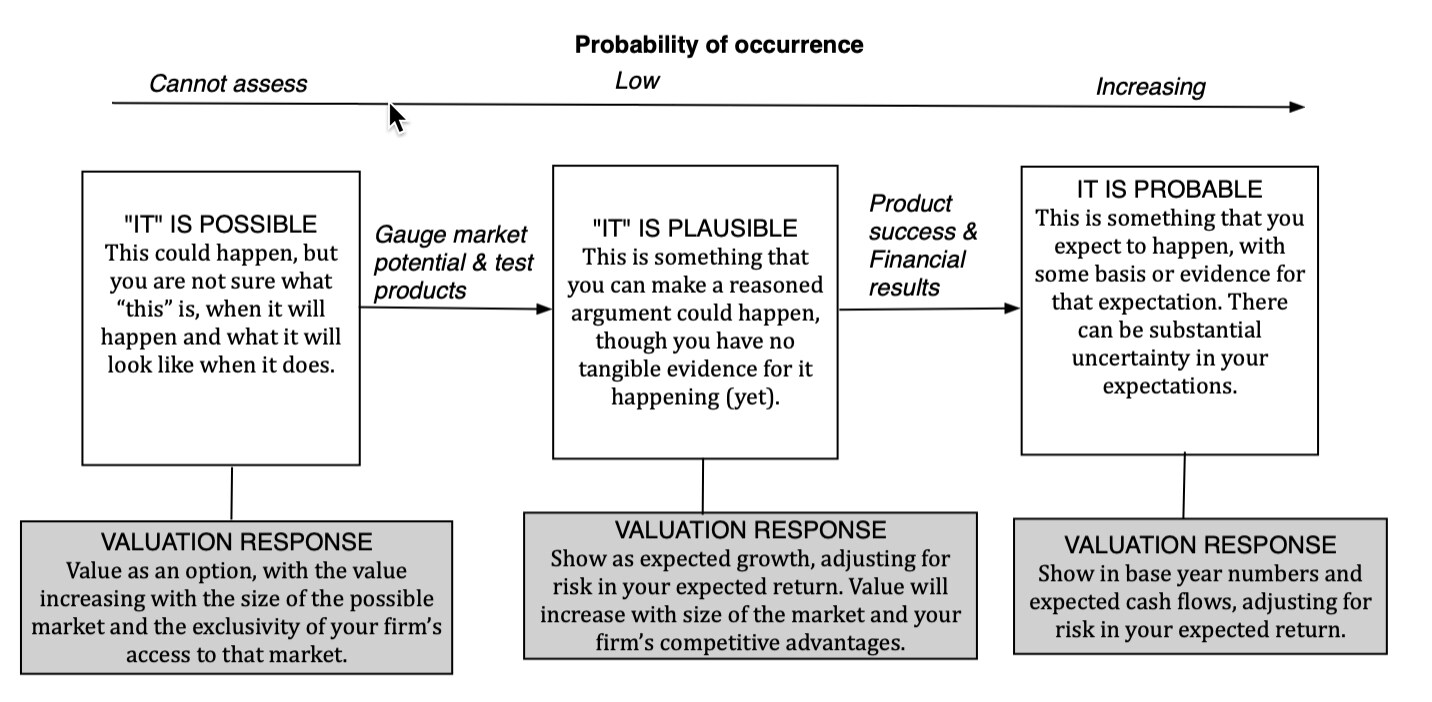

Possible, Plausible And Probable

A common pushback against storytelling is that it allows investors, analysts, and appraisers to let their imaginations run riot, creating fairy tale valuations. It is to counter that possibility that I argue that every valuation story has to go through a three-part test:

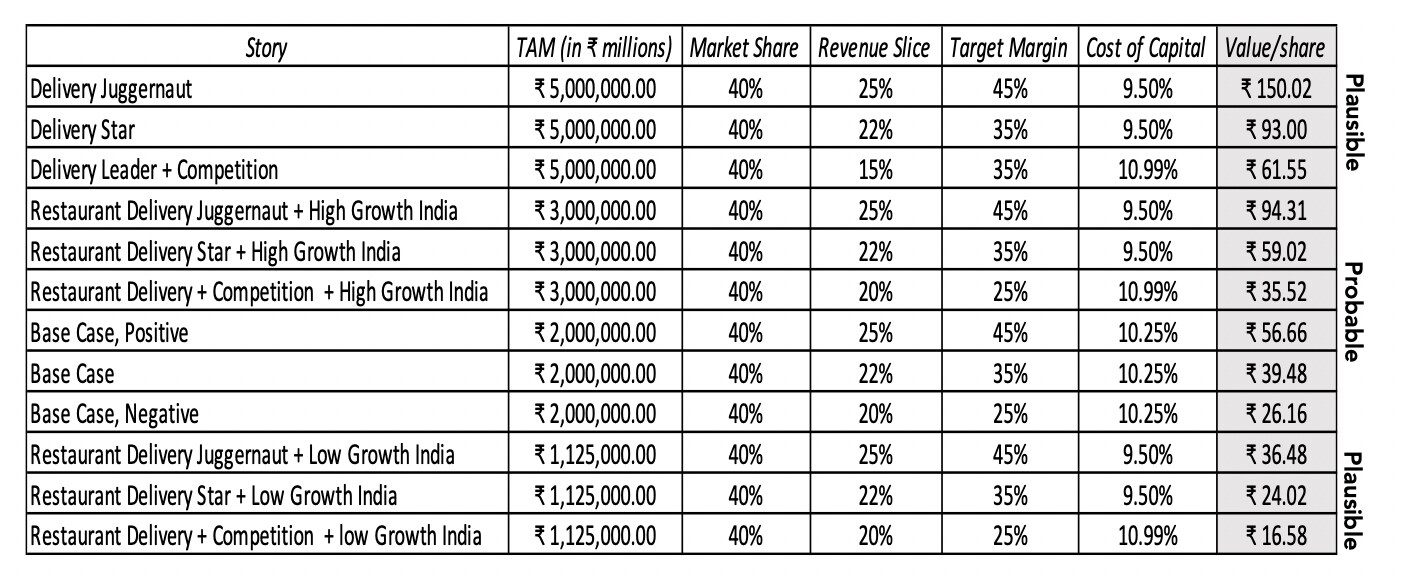

As you navigate your way through the choices, you may be tempted as an optimist to go with the most positive (for Zomato's value) choices on each variable (biggest market, highest market share, highest margin, lowest cost of capital) or the most negative (smallest market, lowest market share, lowest margin, highest cost of capital). In fact, the former is often labeled a ‘best case' and the latter a ‘worst case' valuation, when in fact, neither pass the possible/plausible/probable test, since assuming that you will go after the biggest market will mean accepting lower margins and higher reinvestment. Thus, I could tell you that the best case value is Rs 423 and that my worst-case value is Rs 0, but that would be both useless and misleading. That said, you can already see, no matter what your priors, that there is a whole range of stories for Zomato that pass the test, and that they can yield values per share that are very different:

The most upbeat story that passes the plausibility test, albeit barely, is the one where Zomato targets the food and grocery delivery markets, while maintaining its revenue slice at 25% and margins at 45% (duopoly levels) and a low-risk profile, and even with that unlikely combination of assumptions, the value per share is Rs 150, about 10% higher than its stock price of Rs 140, on August 2nd. Most of the plausible stories fall between Rs 30 and Rs 60, with your views about growth in the Indian economy & delivery market, revenue slice, margins, and risk determining where you fall in the spectrum. This table contains only a small subset of the stories that can be told about Zomato, and I would encourage you to try your hand at the DIY valuation. Once you are done, please go to this Google shared spreadsheet and stake out your value. In a world where we trust crowds to get things right on every aspect of our lives from what restaurant to eat at to what movies to watch, let's get a crowd valuation of Zomato going.

Playing The Zomato Game

I am sure that there are some of you are wondering whether any of this discussion matters, if the market pricing is based upon mood and momentum. After all, if enough buyers line up to buy Zomato shares, perhaps drawn to it by the success of others, there is no reason why the price cannot continue to rise, no matter what the value. I don't disagree with that sentiment, and it goes back to the contrast I draw not just between value and price, but between investing and trading. As an investor, I am having trouble finding a pathway to justify paying Rs 140 per share, for Zomato, even with the most upbeat stories that I come up with, for the company. That may of course reflect a failure of imagination on my part, and you may be able to find a narrative for the company that allows you to invest in the company. As a trader, the question of whether you should buy Zomato comes down squarely to how good you are at playing the momentum game, knowing when to get on, and more importantly, when to get off. For you, the value of Zomato may be irrelevant, and you will need a different set of metrics (charts, price and volume indicators) to make your decisions. I wish I could help you on that front, but trading is not my game, and I have neither the tools nor the inclination to play it. I wish you the best!

Watch here:

Spreadsheets

Aswath Damodaran is a Professor of Finance at the Stern School of Business at New York University. This article was originally published on his blog Musings on Markets.

The views expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of BloombergQuint or its editorial team.

Essential Business Intelligence, Continuous LIVE TV, Sharp Market Insights, Practical Personal Finance Advice and Latest Stories — On NDTV Profit.