After cutting interest rates by more than a percentage point, Federal Reserve officials are now wondering where to stop – and finding there's more disagreement than ever.

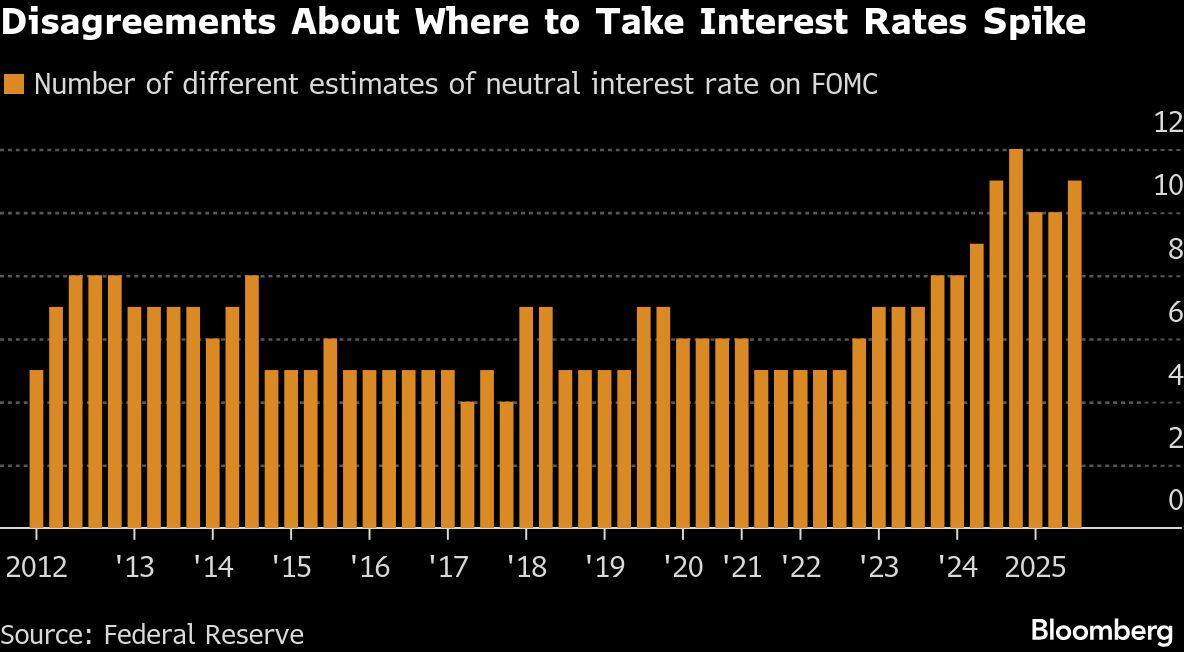

In the past year or so, prescriptions for where rates should end up have diverged by the most since at least 2012, when US central bankers started publishing their estimates.

That's feeding into an unusually public split over whether to deliver another cut next week, and what comes after that.

Fed Chair Jerome Powell has acknowledged “strongly differing views” across the rate-setting committee about which of their two goals – stable prices and maximum employment – to prioritize.

It boils down to a question of whether the economy needs a touch more gas to shore up job markets, or whether policymakers should take their foot off the pedal because inflation is above-target and tariffs could push it higher still.

But that raises another question — one that's more abstract but increasingly important to the whole debate: what rate of interest would neither stimulate the economy nor squeeze it? This is the presumed endpoint of the cutting cycle. It's known as the “neutral” rate. And right now the collective Fed is struggling to figure out what it is.

‘All Over the Place'

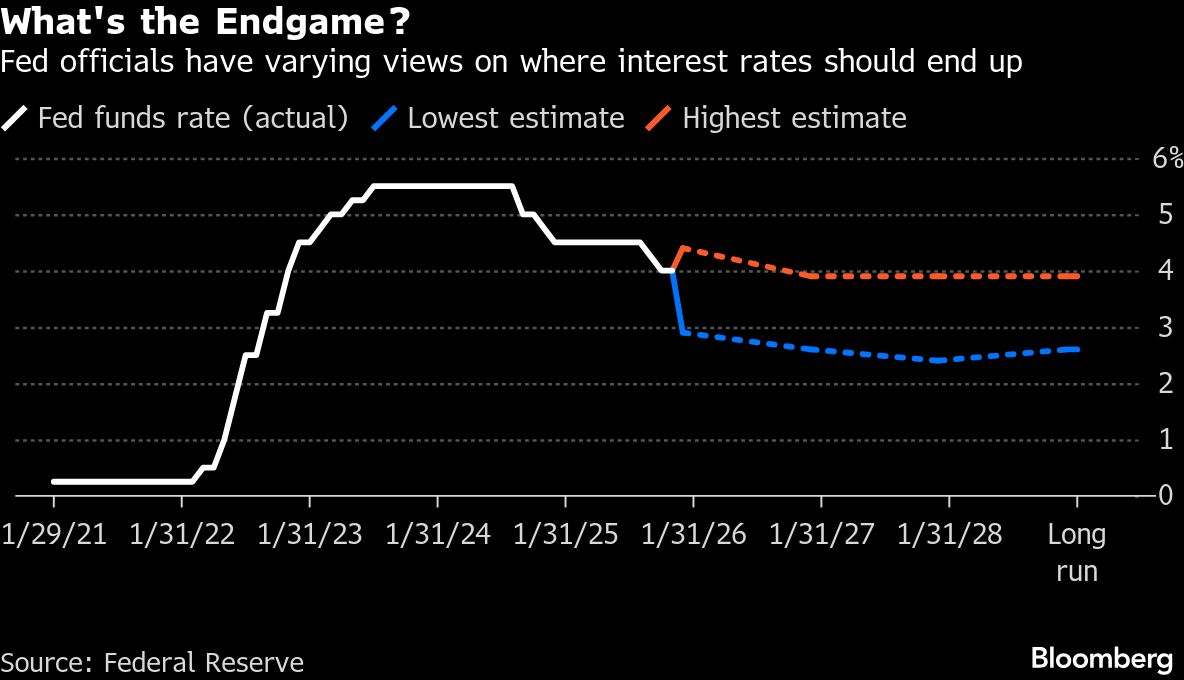

In September, the last time they published projections, 19 officials came up with 11 different estimates, ranging from 2.6% to 3.9% — the latter number being roughly where rates are now. “We have people all over the place,” says Stephen Stanley, chief US economist for Santander. “There's always a degree of disagreement on that, but the current range is wider.”

Stanley also thinks the estimates are becoming more important, as the Fed's benchmark arrives at the upper edge of that range. “It starts to become potentially a binding constraint for some of the more hawkish Fed members,” he says. “It definitely means that each successive cut becomes harder and harder.”

All of this is borne out in some recent Fedspeak. Philadelphia Fed President Anna Paulson explained on Nov. 20 why the twin risks of higher inflation and unemployment, combined with rates that may already be near neutral, have left her heading into the December meeting with caution.

“Monetary policy has to walk a fine line,” she said. “Each rate cut brings us closer to the level where policy flips from restraining activity a bit to the place where it starts to provide a boost.”

The neutral rate of interest is also known as r-star, based on the mathematical notation used to represent it in models, or the natural rate. It can't be directly observed, only inferred, and has generated intense debate for more than a century.

Some economists, including John Maynard Keynes, have questioned whether it's really a useful tool at all — but few modern central bankers would agree. The idea is at the “heart of monetary theory and practice,” according to New York Fed chief John Williams, a specialist on the topic.

He's argued that failure on the part of policymakers to diagnose shifts in the natural or neutral rates of interest and unemployment can have profound consequences, citing the spike in inflation expectations in the 1960s and ‘70s.

The neutral rates are widely seen as driven by long-term shifts in things like demographics, technology, productivity and debt burdens, which affect patterns of savings and investment.

Which Direction?

At the Fed, alongside the lack of consensus on where they are right now, there's also disagreement about which way they're headed. Minneapolis Fed President Neel Kashkari predicts that widespread adoption of artificial intelligence will lead to faster productivity growth, pushing the neutral interest rate up as new investment opportunities boost demand for capital.

Fed Governor Stephen Miran, President Donald Trump's latest appointment to the central bank, says present-day policies should also play a part in the debate.

In his first policy speech after joining the Fed, Miran made the case that Trump's tariffs, immigration curbs and tax cuts have combined to drive the neutral rate lower, even if only temporarily — so the Fed should ease policy sharply to avoid hurting the economy.

Williams last month expressed doubts about allowing short-term changes into the calculation. He argues that global trends such as aging populations are holding estimates of the rate at historically low levels.

New York Fed chief John Williams

For a decade or so before the pandemic, when inflation was subdued and interest rates near zero, policymakers seemed to more or less agree where neutral was. But the surge in prices since then – as well as the uncertainty over trade and immigration, and what AI will do to the economy — have left some analysts wondering if diverging estimates are the new normal.

What's more, the Fed is set for a change of leadership in 2026, with Trump vowing to pick a new chair who's committed to lower interest rates, and the president may have other opportunities to staff the central bank with his allies. The new policymakers are expected to argue for cheaper money, like Miran has, and may also estimate that neutral is lower right now.

‘Only a Tool'

Since the neutral rate of interest is for economists what “dark matter” is to astronomers — something that can't be seen directly — there are policymakers who prefer to judge it, in Powell's words, “by its works.”

St. Louis Fed President Alberto Musalem says low default rates show financial conditions remain supportive for the economy. His Cleveland Fed counterpart, Beth Hammack, says narrow credit spreads imply monetary policy is “only barely restrictive if at all.”

Drawing clues from financial markets, though, isn't a straightforward task. Some Fed officials see the yield on 10-year Treasury bonds, which has been hovering around 4%, as evidence that financial conditions aren't holding the economy back.

Others say that those measures reflect expectations about the economy's path, as well as strong global demand for safe assets, meaning they're of little use when trying to estimate neutral rates.

With so much uncertainty around the outlook, divisions over the neutral rate aren't likely to disappear when Fed officials reveal their latest estimates next week.

Meanwhile, it'll be more concrete things – “the labor data and the price data” — that drive actual policy calls, according to Patrick Harker, who headed the Philadelphia Fed until he retired this year.

The neutral rate is “a useful conceptual tool, but it's only a tool. It doesn't drive policy decisions,” Harker says. “I don't ever remember a case where everybody sat around and the entire conversation was, what is r-star?”

Essential Business Intelligence, Continuous LIVE TV, Sharp Market Insights, Practical Personal Finance Advice and Latest Stories — On NDTV Profit.