Hawaiian coffee farmers have a message for President Donald Trump: Steep tariffs on major exporters such as Brazil will end up hurting them, too.

Hawaii at first glance might seem the obvious beneficiary of tariffs on coffee. It is the only state in the country where the tropical goods grow, with the vast majority of java imbibed by Americans imported from South America and Vietnam. Higher priced foreign imports should, in theory, make the island state's products comparatively more affordable. But growers say the opposite is true: rising prices across the board will hit consumers already struggling with inflation, curbing demand on everything from popular everyday roasts available at grocery stores to luxury Kona beans.

While the discourse around trade and Trump's “Buy American” mantra could draw attention to Hawaiian goods, the upshot for the state's farmers is that “tariffs will probably will hurt us as much as it would hurt the mainland roasters,” said Suzanne Shriner, the vice president of the Kona Coffee Farmers Association and the president of Lions Gate Farms.

Brazil and Vietnam are the world's top producers of java, and Trump has threatened a 50% and 20% levy on those countries, respectively, though Vietnamese officials have said negotiations are ongoing. Brazil, for its part, is weighing countermeasures and could ask for a reduction in the levies.

But if tariffs hold, even at a lower rate, they would be a blow to US consumers and companies that have already faced surging costs over the last year as poor weather impacted global coffee production. Americans' beloved morning cup of joe could get even more expensive as the cost of tariffs start getting passed down to consumers, and that could risk a ripple effect of decreased consumption.

“Any time you drive up costs to the point where buyers reduce their demand, if people leave the coffee market in the sense that they'll switch to an energy drink versus a cup of coffee, that's going to harm us,” said Shriner.

Starbucks Corp. could take about a 1.4% earnings hit if tariffs on Brazil increase from the current 10% to 50%, according to TD Cowen analyst Andrew Charles. who estimates that more than 20% of the roaster's North American beans come from Brazil. Starbucks had boosted lobbying spending earlier this year to the second-highest quarterly amount on record, noting tariff-related issues.

Trump has said his tariff campaign is aimed at rewriting trade practices he thinks are unfair to the US and encouraging a reshoring of production, from cars to metals mining.

Coffee, however, is not an imported commodity that can easily be replaced.

“Unlike other cases where tariffs may address unfair practices or incentivize domestic producers, coffee simply cannot be grown in most of the United States,” National Coffee Association president Bill Murray wrote in a letter to the US Trade Representative requesting an exemption from tariffs back in March.

Little Room to Expand

Coffee is more popular in the US than even bottled water, with two-thirds of Americans drinking it every day. Those drinkers average three cups daily, according to the National Coffee Association.

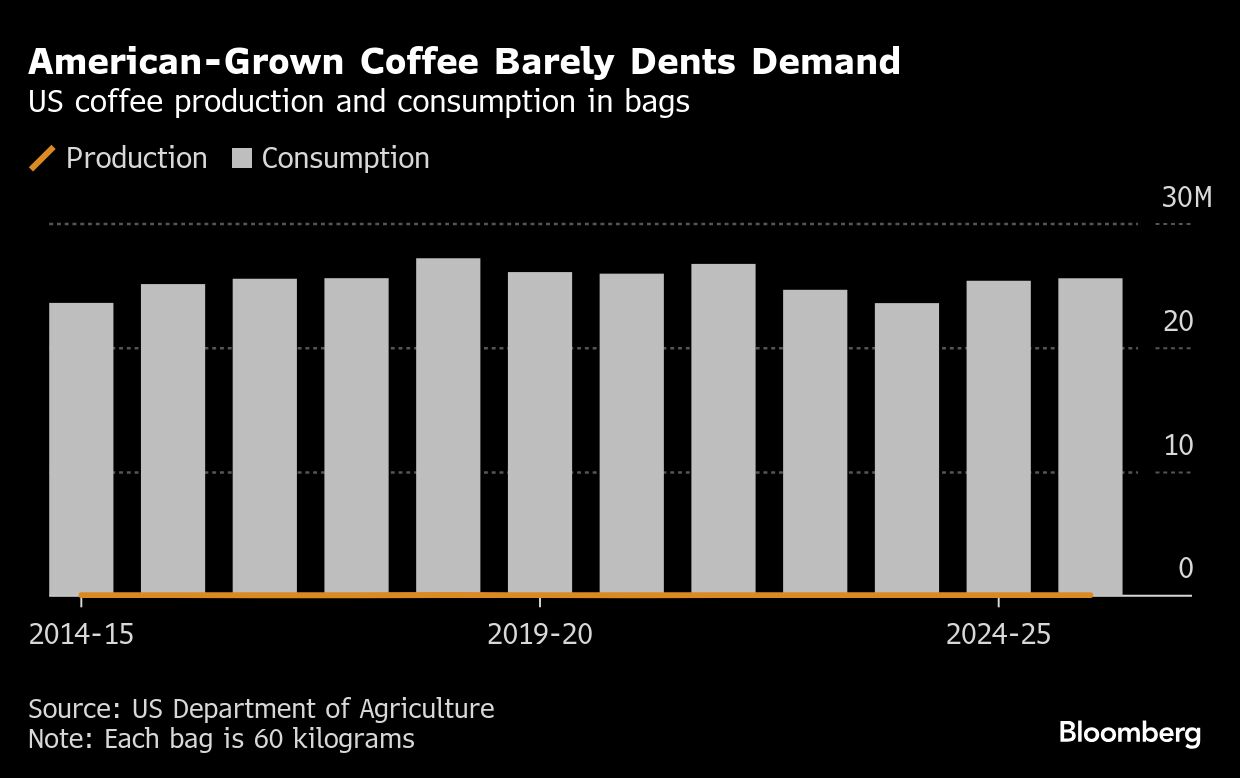

The US imported more than 450,000 tons of unroasted coffee from Brazil in 2024, valued at nearly $2 billion, according to the US Department of Agriculture. Hawaii is seen producing just 12,040 tons of coffee cherries in the 2024-2025 season, a figure that will shrink once the cherries are processed into beans, USDA data shows.

Such production “is not anywhere near the scale required” to meet US demand, Murray said in the letter. The association declined to comment on the latest Brazil tariffs.

Hawaiian farmers don't see much room to expand production significantly, constrained by land, labor and climate. But demand has plenty of space to drop, especially if consumers decide that their “affordable luxury” isn't cost-effective anymore.

“If they like drinking their Starbucks and then they come to Hawaii and they're like, ‘Oh, I'll get the good stuff,' that's awesome. But if we price them out of a coffee at home, then we're going to price them out of exotic coffees too,” said Adam Potter, who owns or manages about 18,000 cocoa trees on the Big Island and farms another 3,000 coffee trees.

Economists and consumers have been bracing for higher prices stemming from Trump's tariff campaign. So far, the impact has been relatively muted, though June's consumer price index, which excludes the volatile food and energy categories, showed some companies are starting to pass on higher import costs.

Hawaiian coffee farmers received about $21.90 per pound for green coffee in the 2024-2025 marketing year, according to the USDA. By the time that makes it to consumers, the best quality beans can cost even more. A pound of roasted coffee from Ka'awaloa Trail Farm in Big Island's famed Kona coffee-growing region retails for $60. Even at a current record high in data going back to 1980, a pound of ground roast coffee in the US averaged just over $8 a pound, according to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics.

“If the price of, let's say, Maxwell House, doubles at the grocery store, I don't think people are going to be like, ‘Oh, now I'm going to buy Kona coffee,'” said Tony Tate, who along with his partner runs Ka'awaloa, a 7-acre coffee and cacao farm.

‘Bad News'

The chocolate industry has also been pushing for an exemption from tariffs. Hawaii's cocoa production is barely existent, not even topping 50 tons of dry beans in 2022. The US imported nearly 200,000 tons of cocoa beans last year — and that's already after a significant drop due to lower global production, according to the US Department of Agriculture.

Hershey Co. said in May that it would seek an exemption, citing as much as $20 million in tariff costs during the second quarter. Unmitigated impacts could rise to $100 million later in the year after working through existing inventories, the company said.

A tariff would have to be “so high, like hundreds of percent, to make it start to be competitive — and then there'd be no chocolate,” said Mānoa Chocolate founder Dylan Butterbaugh. The company uses both Hawaiian and imported beans to produce about 50 tons of chocolate each year.

Lonohana Estate Chocolate's plans to expand are also being stymied. The Honolulu-based company already grows raw cacao and churns out cocoa liquor every day, and is trying to take on the next step of processing — extracting butter and powder from the liquid. But Trump's levies on China, the only country currently making new machines in the necessary size, have complicated the project, said founder Seneca Klassen.

“Not only has the machinery come up in price, the instability of the marketplace has to be priced into financing,” he said. “Everything gets more expensive, everything gets less reliable. It's just bad news for business.”

Essential Business Intelligence, Continuous LIVE TV, Sharp Market Insights, Practical Personal Finance Advice and Latest Stories — On NDTV Profit.