Gyati/Manas/Guwahati (Assam); Attapadi, Palakkad (Kerala); Sirumugai/ Thadagam, Coimbatore (Tamil Nadu): "O mor hai hastir kanyare (O daughter of the elephant)”--Leena Mahato often hums this Assamese folk anthem about a Brahmin's wife who is expelled from home but finds shelter among elephants and is crowned the queen of the herd. Leena's mother comes from the Rabha tribe of the northeast, known for its skilled mahouts, and she grew up on stories of the close bond between elephants and men.

Clad in a grey mekhala-chador (an Assamese saree ensemble), 32-year-old Leena knows that this idyllic world is long gone, as living space runs out for India's largest mammal and a growing human tide decimates and invades its habitat. India's human-population density rose 116 percent over 40 years, from 177 persons per sq km in 1971 to 382 in 2011: It is also home to 27,312 Asiatic elephants, the world's largest population, although this is down by half from over 50,000 elephants in the early 20th century, said Raman Sukumar, Asian elephant ecologist and a specialist on human-elephant conflict.

In northern Assam's Chirang district, rice is cultivated, villages expand and roads are built in land where elephants, until recently, roamed relatively free. Until 2011, 35.28 percent of Assam was covered under tropical forests. By 2016, this came down to 20 percent. Trying to scrape a living from the land, Leena's husband Raju, a farmer, regards elephants as no more than pests.

“They are constantly raiding my 8-acre paddy field,” he complained. "We have tried everything from firecrackers to solar-powered fences. The only thing that remains is to either kill the elephants or kill ourselves." Indeed, as IndiaSpend travelled through the elephant corridor of upper Assam, farmers poisoned elephants or linked solar-powered fences--meant to stun but not kill elephants--to high-tension electric lines to make sure they died.

These stories are repeated across India wherever human settlements are perched on the edges of forests, in states rich and poor, such as Kerala, Tamil Nadu and Jharkhand.

India has lost nearly 2,330 elephants or 10 percent of the population since the last elephant census in 2012. From around 30,000 in 2012, the figure dropped to 27,312 in 2017. Electrocution, train accidents, poaching and poisoning caused nearly 77 percent of elephant deaths (500 of 655) between 2012 and 2017, according to 2012 census data. The rest died as habitats were lost.

As their habitat diminishes, elephants get pushed into increasingly smaller areas and reduced access to food, which affects reproduction rates and spurs conflict with humans. Elephant herds migrate 350-500 sq km annually through swathes of forests and grasslands known as elephant corridors, which link their habitats.

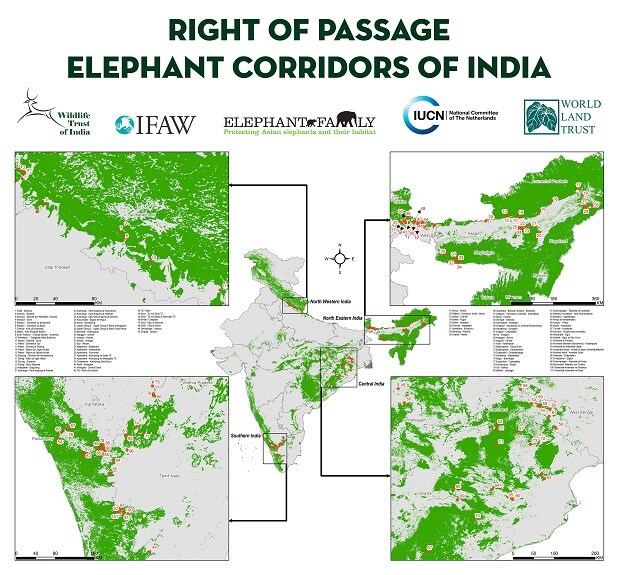

There are 101 elephant corridors across India, of which 70 percent are regularly used--primarily in south India, West Bengal and the northeast--and 25 percent occasionally used, according to this August 2017 report. National or state highways cut across two-thirds of these corridors, and 74 percent are 1 km or less in width, up from 46 percent with this width in 2005.

As a consequence of being squeezed out of their homes and migratory routes, India, home to the world's largest population of Asiatic elephants (27,312), also ranked first globally over five years to 2017 by elephant deaths, according to the Synchronized Elephant Population Estimation India.

We found in our investigations in three states that laws to protect elephant habitat and migratory corridors are being violated, there is only sporadic action to deal with frequent collisions on railway tracks and deliberate murder of the animals by poison or electrocution is becoming common.

In the latest incident, in Kamalanga village in Odisha's Dhenkanal district, seven elephants died of electrocution on October 26, 2018.

Odisha is not new to such slaughter: 109 elephants died of electrocution over nine years to 2018; that is 12 elephants a year or an elephant every month, according to the state forest department.

Two days after the Dhenkanal tragedy, chief minister Naveen Patnaik ordered a police inquiry (meanwhile, the National Green Tribunal imposed a fine of Rs 1 crore), dismissed an official and suspended six for “negligence”. But wildlife activists are sceptical of such inquiries and fines, as the elephant population falls.

Too little, but not too late . There are temples dedicated to elephants across India. But the only God our politicians now worship is money. If the enquiry is real, the trail will lead back to the Cam's office. But I'm not holding my breath @SanctuaryAsiahttps://t.co/EzftxFJtEk

Two elephants every sq km in Manas: Why coexistence is hard

In Assam, where our story begins, 38 elephants died in the first 10 months of 2018, according to Rathin Barman, joint director, Wildlife Trust of India, a nature conservation organisation. That is 47.5 percent of the elephants that die every year in India--about 80, as per the elephant census of 2017.

Forty elephants died of unnatural causes--electrocution, poisoning, collision with speeding trains, and accidents caused when the animals walked into ditches in tea estates and constructions sites and other man-made structures--between September and December 2017, said a December 2017 study by Aaranyak, a wildlife NGO based in Guwahati.

On October 27, 2018, the same day as the Dhenkanal tragedy, an elephant fell into a ditch and died in Thurajan tea estate in the Golghat district of upper Assam, and an adult elephant was found dead at Janjimukh in Jorhat.

Day of death for jumbos in #India: A calf died after falling in Dutch at Thurajan tea estate in #Assam's #Golagaht district while an adult was found dead at #Janjimukh; happened on the day 7 elephants were electrocuted in #Dhenkanal, #Odisha @abaruah64 @the_hindu pic.twitter.com/ndSsqzqjQA

"We have two elephants for every square kilometre in Manas in Assam,” said Hiranya Sharma, field director of Manas Tiger Reserve. “However, the settlements are designed in a way that the tea gardens and labour colonies lie between the forests and the water bodies. Elephants trample through all these to reach water. People feel they have no option but to try and eliminate the elephants to ensure their own survival.”

Between 2014 and 2015, the state also recorded 54 human deaths traceable to activities of wild elephants. Chirang, Sonitpur, Goalpara and Golaghat districts are the primary conflict zone in Assam, according to NK Vasu, principal chief conservator of forest and head of forest force, Assam.

Kerala tops the list of states with most elephant deaths

Kerala has the third largest elephant population in India as of 2017--3,054. But it is not even half the numbers it reported in 2012; in a space of five years the elephant population is down by 52.44 percent.

"With forests thinning out, elephants in most parts of the country are increasingly dispersing into areas with high density of human population," said Subin K Mohan, assistant professor at the College of Veterinary and Animal Sciences at Pookode in Kerala's Wayanad district.

The man-elephant conflict in the state has also proved brutal for humans: It killed 22 people in 2016-17, according to the Kerala Forest Department data. The state has handed out Rs 9.63 crore as compensation for these deaths.

"Before the floods in 2018, six people were killed by elephants in Kerala within two months,” said T Sankaran, a former official with Kerala Forest Department. “In what almost looks like revenge, an equal number of elephants were killed by electrocution from high-power fences installed by frustrated villagers across Kerala. They look at elephants not as magnificent creatures but as overgrown crop pests.”

In the small hamlet of Attapadi in Kerala's Palakkad district, spanning less than 900 sq km, five elephants have been killed in as many years due to electrocution from electric fences. This village is close to the Attapadi Reserve Forest. The Assam story plays out here too.

"Locals are supposed to use solar powered wires as fences--these emit a charge of not more than 5,000 Watt, enough to shock and scare the elephant back into the forest but not kill it,” said Sankaran. “However, elephants are creatures of high intellect. They break the fence with a wooden log or branch and march through. Frustrated villagers then connect solar fences to high-tension power lines. These emit about 12,000 Watt--enough to kill an adult elephant.”

Attapadi farmer V R Rajagopal, 63, who has been farming for over 33 years, had another insight into these deaths. "Till even a decade ago, there was not as much conflict in these parts,” he said. “It all started with the liquor ban. People started brewing liquor at home and elephants came, drawn by the smell. They rampage through farms, break into houses and look for liquor and food grains.”

Critical southern elephant corridor disrupted by construction

An elephant corridor is a continuous stretch of woodlands that the animals cross through while moving from one forest to another each time the season changes. This corridor connects various elephant habitats from the tip of the Western Ghats in the deep south of the Indian subcontinent to the lower reaches of the Himalayas in Uttarakhand and eastwards, all the way to Vietnam.

Human-elephant conflict develops when these elephant corridors give way to human settlement or agriculture. Common examples of the fragmentation of elephant corridors are coffee estates in south India, infrastructure projects and farms in Karnataka, and stone mines, railway tracks and tea estates in Assam.

Habitat fragmentation from human activities and unplanned development is one of the “greatest threats” to elephants in north-eastern and east-central India, said Sukumar, the elephant specialist.

Humans look at the conflict differently.

Take M Gopal, who owns about 5 acres of land at the foothills of the Western Ghats in Sirumugai in Coimbatore District. He cultivates bananas but harvests only half. Elephants ruin the rest, eating the stem and crushing the fruit, he said. Gopal is frustrated enough to quit agriculture.

"It takes me 10 to 12 months to get one harvest,” said Gopal. “Ideally, I should be getting a yield of at least 4,000-5,000 fruits from my land. However, my yield in the past two years has not gone beyond 1,200 to 1,500 fruits."

#BIGNEWS: Elephant menace continue in #Hassan. The jumbos have destroyed several acres of fields and the residents are also constantly living in fear. Residents allege their repeated complaints to forest officials have fallen on deaf ears. pic.twitter.com/QHVl69Reo2

Sometimes crops are ruined, and at other times, people die.

"My daughter never got to see her fifth birthday present,” recalled Latha Sivakumar, 26, a resident of Thadagam on the fringes of Coimbatore. “She had asked for a doll and I bought her one. Both my doll and the doll were trampled by elephants four days before her fifth birthday. The elephant herd was raiding our hut for the foodgrain we store at home after harvest."

When you will irritate wild animals they will fight back, never forget that jungle is their habitat and we have destroyed it.

There is thin line between bravery and stupidity its good that wild elephant didn't lose its calm.

Video Credits: Anonymous pic.twitter.com/TPv5ipHp6MBut elephant corridors have not only been obstructed by farmers. A systematic violation of laws has led to a mushrooming of buildings in the middle of migratory paths trod on by elephants for centuries.

Around 20 institutions built on a migratory corridor

Habitat fragmentation caused by structures obstructing elephant pathways are a problem across the country, especially in central-eastern and southern India.

Take for instance the Isha Yoga Foundation headquartered at the foothills of the Velliangiri near the southern Tamil Nadu city of Coimbatore. In July 2018, the government's auditor, the Comptroller and Auditor General of India, concluded that the foundation constructed various buildings between 1994 and 2008 on an area of 32,856 sq ft in Booluvapatti village without permission from the Hill Area Conservation Authority, a state-level body under the ministry of environment and forests which clears any developmental activity in the hill area.

The foundation falls in south-western Tamil Nadu's Booluvampatti-Attapadi corridor, home to more than 50 percent of plant species consumed by elephants, and a route that connects to Silent Valley National Park in neighbouring Kerala and the Kallar-Gandhapallam corridor which connects the elephant habitats between Kerala and Tamil Nadu.

Isha denied violations. "Isha Yoga Center does not lie on any forest land nor does it lie on any elephant corridor in the Coimbatore region as per studies by the Wildlife Trust of India, WWF or the Tamil Nadu Forest Department,” said P Sandeepan, a foundation volunteer since 2010.

There are about 20 other institutions on the elephants' migratory corridor including the Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeeth University, Marudhamalai temple, Karunya University, Karl Kubel Institute for Development Education, the Salim Ali Centre for Ornithology and Natural History, Tamil Nadu Agricultural University, Forest College and Research Institute, a Central Reserve Police Force training centre and many private schools and engineering colleges, according to data given to IndiaSpend by the Coimbatore Forest Division.

Apart from this, 190 brick kilns have mushroomed in the Thadagam valley in Coimbatore district alone, an elephant migratory corridor. There are 88 elephant corridors--20 in southern India--“being currently used” nationwide, according to a 2017 study “Right of Passage, Elephant Corridors of India”, released by the Wildlife Trust of India.

The foremost reason for habitat degradation, said Sukumar, is mining. “In most cases, restoration of forests does not take place after the mining activities are over,” he said, explaining that another consequence of corridor invasions is the growth of new plant species--often inedible to elephants--that crowd out previously edible plants.

While multiple factors endanger India's elephant population, there are innovative, though scattered, efforts being made to resolve the conflict. One of these is the use of a simple device to warn elephants off dangerous paths.

Some solutions: How Bengal, Assam try to prevent rail collisions

The Northeast Frontier Railway covering northern West Bengal, parts of eastern Bihar and the north-eastern states, cuts across 27 elephant corridors. In Assam and West Bengal--which have seen many elephant deaths on rail tracks--locals and officials have developed a unique buzzer that emits a buzzing sound.

A simple device, which costs around Rs 2,000 to assemble, amplifies the recorded sound of honeybees. Railway officials in consultation with the forest department have tested the device on elephants in the forests to check its efficacy before installing it in the migratory corridors of the division. The project was first implemented in 2017 in Assam between Kamakhya and Azara railway stations near Guwahati.

"The project was then taken to the railway line between Kalchini and Rajabhatkhawa situated just outside the Buxa Tiger Reserve in the Alipurduar district of West Bengal,” said Chandraveer Raman, divisional railway manager, Alipurduar division. “The result was immediate and elephants avoided the route once the buzzer was sounded. It is audible up to 600 metres and we start it only when a train is approaching at the same time that a herd is crossing.”

There has been only one elephant death at the crossing this year, said Raman. The 128-km railway line between New Jalpaiguri and New Alipurduar has been a graveyard for elephants with as many as 65 deaths since 2004.

In Coimbatore district too, several NGOs have come up with buzzers that sound an alarm when the elephant herd is as far as 10 km away. This gives villagers the time to get out of its path and also alerts the forest department which then deploys guards.

Experts stressed the need to involve local populations in framing wildlife policies. "More often than not, local communities will have a better understanding of living with elephants because it is a question of their survival," says wildlife expert Ravi Chellam. "While drafting policies, their inputs should be sought. Currently, most policy-making does not involve the local population sufficiently citing that it is a tedious and time-consuming process.”

For instance, if the Kattunayakans, a tribe in Tamil Nadu's Nilgiris district, were consulted, they would explain that the elephant has the primary right to the land and its resources.

"It is his (elephant's) land that I have encroached upon,” said Muthu Subramani, a Kattynayakan farmer who loses some of his plantain yield to elephants every year. “My share is only after he takes his due."

It is a sentiment that fewer Indians identify with each year.

(Rajeshwari Ganesan is an independent journalist and a wildlife enthusiast.)

Essential Business Intelligence, Continuous LIVE TV, Sharp Market Insights, Practical Personal Finance Advice and Latest Stories — On NDTV Profit.