- Trump threatened 100% tariffs on China from November 1, risking renewed trade tensions

- Global debt hit nearly $338 trillion in the first half of the year, a record high

- IMF warns of tech market fragility, comparing current valuations to the 2000 dot-com bubble

The world economy has so far withstood the biggest barrage of US tariffs since the 1930s as American consumers continued to spend, companies absorbed higher costs and an AI boom fueled a new breed of animal spirits.

But President Donald Trump's latest threat to impose massive tariffs on China products has stoked renewed fears of another shock for the global economy, compounding warnings of surging government debt and a bubble in technology stocks.

Those concerns will dominate this week's gathering of finance ministers and central bankers, who are descending on Washington for the International Monetary Fund and World Bank's annual meetings. The US's $20 billion lifeline to help shore up Argentina's peso and proposals to deploy frozen Russian assets for Ukraine will also be high on the agenda of meetings on the sidelines.

Policymakers are convening against a background of fresh trade tensions between the world's two largest economies and political instability in countries from France to Japan.

Last time they were in DC, back in April, the economic outlook was much darker. Trump's announcement of “Liberation Day” tariffs sent shudders through financial markets and worried policymakers about a global downturn marked by trade retaliation, surging inflation and a drought in investment.

Over the last six months, though, most surprises have been on the upside, especially in the world's largest economy.

US gross domestic product grew in the second quarter at the fastest pace in nearly two years. Even after Trump's fresh tariff threats hammered markets on Friday, the S&P 500 Index has surged 32% since an April low. Underpinning both stocks and the real economy: artificial intelligence and record investment in data centers needed to power cloud computing.

Companies have thus far navigated the tariff disruptions by fattening inventories over the short run and accepting thinner margins instead of passing the costs of higher duties to consumers.

“This resilience has been welcome but I don't think it's sustainable,” Karen Dynan, an economics professor at Harvard University and nonresident senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, said during a briefing last week. “We are going to see a slowing of the global economy.”

On Friday, the US president said he would hit China with an additional 100% tariff from Nov. 1 — acknowledging he could retreat from the escalation if the Chinese backed down from threatened restrictions on rare earths.

Bloomberg Economics' latest forecasts call for a slowdown in global economic growth next year. The economists see a 3.2% increase in real gross domestic product in 2025, unchanged from last year, and a 2.9% gain next year.

Surging Debt

Surging debt for both advanced and emerging economies is set to feature prominently during the Washington discussions. Global debt rose by more than $21 trillion in the first half to a record of almost $338 trillion, a scale of increase similar to that seen during the pandemic, according to the Institute of International Finance.

The Trump administration's efforts to shore up Argentina's economy before midterm elections later this month will also be a key topic. The IMF agreed to lend more money to Argentina in April, but only over widespread internal objections. The fund's managing director, Kristalina Georgieva, has been involved in recent talks with US and Argentinian officials.

US payroll growth has proven to be far less robust than expected as companies slowed their hiring — the country's manufacturing sector outright shed jobs for four straight months. A measure of China's factory activity in September extended its stretch of declines to a sixth month — the longest slump since 2019. Germany's economy contracted by much more than initially estimated during the second quarter, and its export-dependent auto factories are reeling.

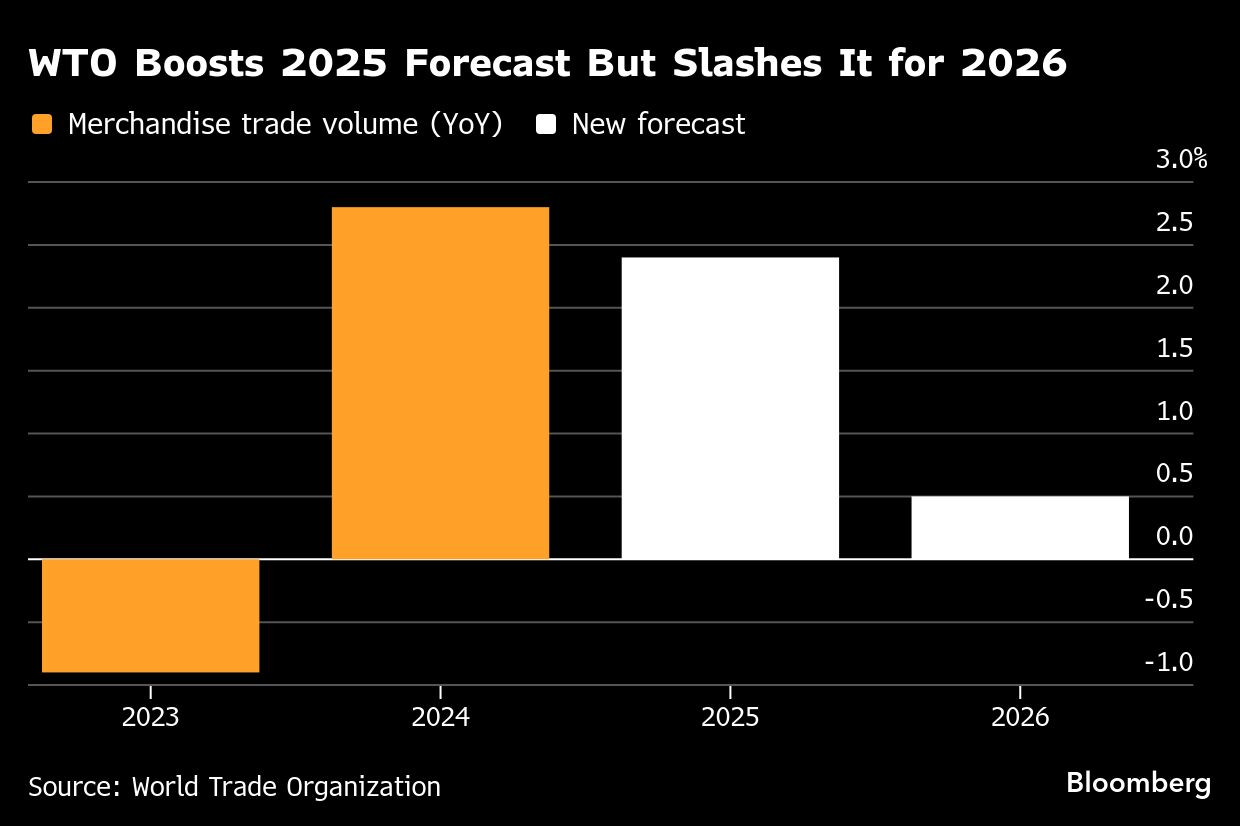

The growth of global goods trade is expected to slow significantly next year, reflecting a delayed drag from Trump's tariffs, the World Trade Organization said on Oct. 7. Merchandise trade volumes are forecast to rise just 0.5% in 2026, compared with 2.4% this year, according to the the Geneva-based forum.

“Headwinds to the global economy are stiffening,” said Frederic Neumann, chief Asia economist at HSBC Holdings Plc in Hong Kong. “While it's tempting to believe that global export volumes can remain unscathed by US tariffs, payback from earlier front loading appears inevitable.”

One of the biggest questions remains whether higher prices eventually derail the US consumer, with knock-on consequences for the world too. While the impact from tariffs on global economic activity has been smaller and shorter-lived than feared earlier this year, “there's another shoe to drop,” according to Nathan Sheets, global chief economist at Citigroup Inc.

“The tariffs are increasingly biting, which is likely to bring further softening in US consumption and import demand,” Sheets and colleagues wrote in a recent note, forecasting global growth will slow to below 2% in the second half and then bounce back to 2.5% next year.

Eurizon SLJ Capital Chief Executive Officer Stephen Jen says it may take six to eight quarters for the tariff shock to hurt consumption and push US economic growth toward zero, based on past import-price shocks.

“Tariff shocks have been amortised into half-a-dozen bits of 2% import price shocks, rather than a one-off 13% tsunami,” he wrote in a recent note.

Among those warning that the tariff shock is not yet over is Mike Brundidge, who runs Seattle-based Acme Food Sales Inc., which imports food such as canned tuna and coconut water from around the world for major US retail chains.

Until now he has absorbed some of the hit and passed along some costs to his consumers. But he cautions that higher prices are on the horizon.

“Very few things in life are certain but I can guarantee you prices on the shelf for the consumer in a grocery store are going up. There's just no way around it,” he said

Tech Fragility

Another near-term concern centers around a reversal of the AI exuberance.

“Today's valuations are heading toward levels we saw during the bullishness about the Internet 25 years ago,” IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva said in a speech on Wednesday, an apparent reference to the dot-com bubble that burst in 2000. “If a sharp correction were to occur, tighter financial conditions could drag down world growth, expose vulnerabilities, and make life especially tough for developing countries.”

In a scenario modeled by Oxford Economics, a US-focused tech slowdown would send the world's biggest economy inching toward a recession and drag global growth to 2% in 2026 instead of a baseline 2.5% — with the prospects for an even bigger hit.

Which is why economists are now increasingly eyeing the tech sector for fragilities, along with the continued uncertainty linked to tariffs. The AI frenzy doesn't necessarily lend itself to a longer-term growth engine, according to Alexis Crow, chief economist at PwC US.

“The verdict is still out as to whether or not this investment boom will lead to sustainable improvements in productivity and hence a significant up tick in growth,” she said.

Essential Business Intelligence, Continuous LIVE TV, Sharp Market Insights, Practical Personal Finance Advice and Latest Stories — On NDTV Profit.