Abdallah Arara has raised 11 children and worked 400 head of sheep on the same plot of land five miles east of Jerusalem for most of the past 45 years. His parents arrived in the early 1950s after Israeli troops forced them out of the Negev, a desert further south.

Now, his family may be forced to move again.

“At any minute, the Israelis will come and evict us,” said Arara, 60, one of several thousand members of the Jahalin Bedouin tribe, who live among the rocky hills and dunes on the road to Jericho from Jerusalem in the Israeli-occupied West Bank.

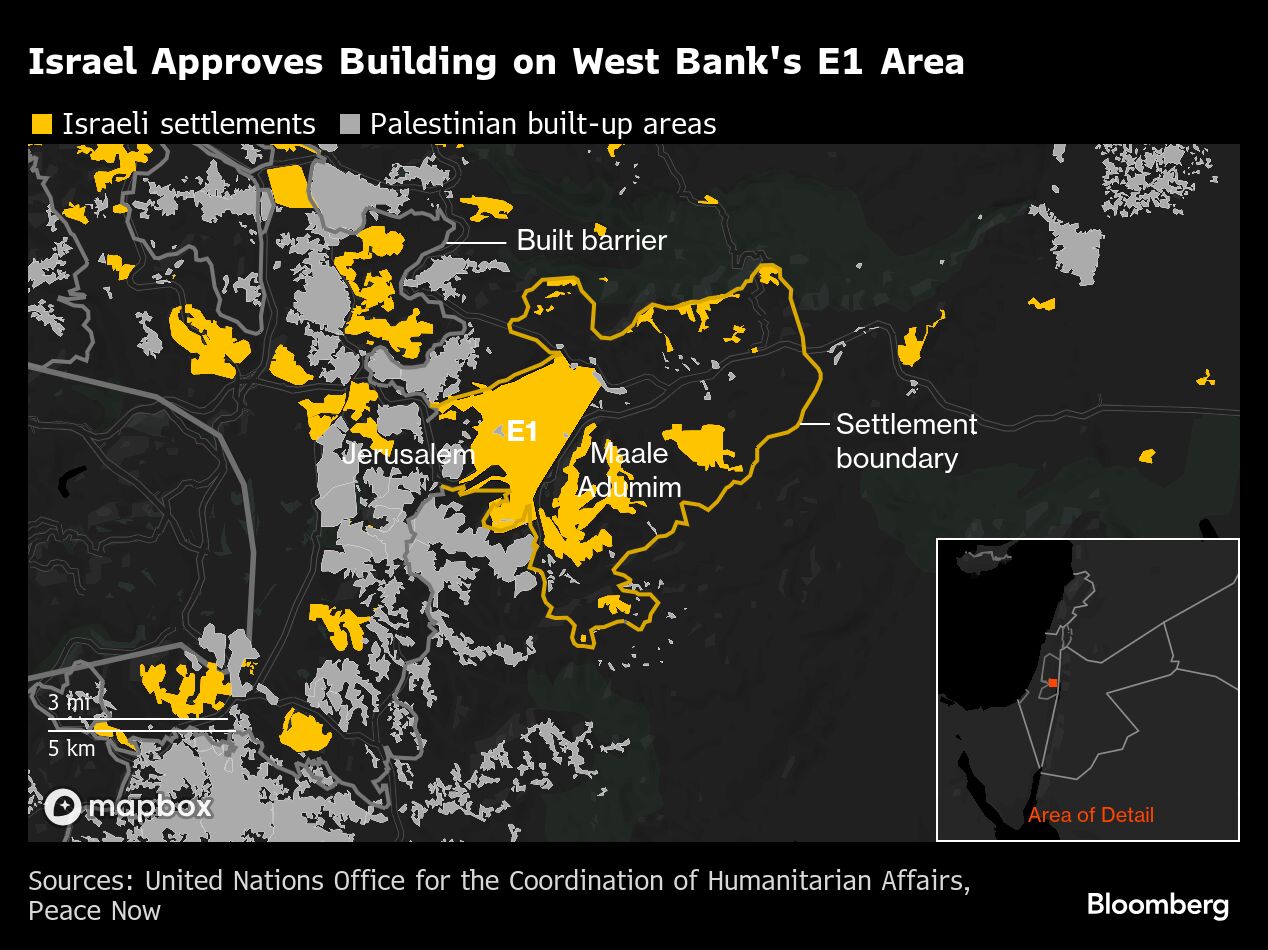

His fears stem from the Israeli government's decision last week to approve the building of 3,400 housing units in the mostly empty area known as E-1 between Jerusalem and the Jewish settlement of Maale Adumim. That's where Arara and the rest of the Bedouin live.

The move came after three decades of delays caused by concern for the rights of the Bedouin and because E-1 — which abuts Jerusalem and connects the northern and southern parts of the West Bank — is considered critical for the viability of a Palestinian state. In the event of an Israeli takeover, it would split the Palestinian-held parts of the territory in two.

That's the point, according to Israeli Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich, who said the decision to build there “practically erases the two-state delusion and consolidates the Jewish people's hold on the heart of the Land of Israel.”

Since being announced, Israel's push into the E-1 area has been condemned by several countries. A group of more than 20 governments — including the UK, Australia and Canada — slammed the move as “unacceptable and a violation of international law.” The Organization of Islamic Cooperation called it an “illegal attempt to alter the geographic and demographic landscape of the occupied Palestinian territory.”

The decision illustrates a shift in Israeli policy to one more openly in favor of West Bank expansion. For years, settlers were marginal, even extremist figures, with some of their theorists and leaders banned from elections. But as Israeli society has grown more religious and nationalistic they've become increasingly influential. Today, numerous government ministers — Smotrich included — live in settlements that most of the world considers illegal.

Meanwhile the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, never calm, is in a particularly aggressive phase. The war in Gaza, the smaller of the two Palestinian territories, has raged for almost two years — ever since Hamas militants launched a deadly attack on Israel from the enclave in October 2023. Israeli troops are currently preparing an assault on Gaza City, the de facto capital, in a final push to destroy the Iran-backed group.

The West Bank has at the same time seen an upturn in settler violence against Palestinians, while Israeli soldiers have intensified ground raids and airstrikes in the hunt for militants. On top of that, European powers including the UK and France have joined Arab nations like Saudi Arabia in saying they would support the recognition of a Palestinian state, with French President Emmanuel Macron saying this week that “lasting peace will be brought about by a sovereign Palestinian State.”

The government of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu — the most right-wing in the country's history — has vowed to expand the 550,000-strong Jewish settler population. That includes the E-1 extension to Maale Adumim, a town of more than 40,000 Israeli Jews, by building homes for another 15,000 people.

(Source: Bloomberg)

“I was born here and I want to make sure that the younger generation can continue to live and thrive here,” said Guy Yifrah, 43, the mayor of Maale Adumim. “We haven't built a new neighborhood in 20 years and we need 800 new units each year just to accommodate natural growth.”

Yifrah, like most Israelis, opposes a Palestinian state, saying the 2023 attack by Hamas showed that Israel needs broader boundaries to survive in an area populated by groups that would see it destroyed. But he took issue with the argument that building in E-1 would drive a stake through the heart of the concept.

E-1, he notes, is only 12 square kilometers (4.6 square miles) large, leaving a further 20 km between the area and the Jordanian border over which a road could be built to connect the northern West Bank to the south. Others counter that the relevant terrain is steep and treacherous, making road building extremely difficult.

For many on both sides of the dispute, the issue of E-1 is more about its proximity to Jerusalem. Palestinians say their state must have part of Jerusalem as its capital; Israel says all of united Jerusalem is its eternal capital.

“The real significance of E-1 is to stop the nonsense idea that Jerusalem can be the capital of a Palestinian state,” said Israel Ganz, who heads the Jewish settler movement in the West Bank and presides over the Binyamin regional council of several dozen settlements not far from Maale Adumim.

On Tuesday evening, he and his council held a gala dinner to celebrate the announcement of 17 new settlements in his region. Netanyahu was the guest of honor.

“I promised 25 years ago that we would deepen our roots, and we have done so, together,” Israel's longest-serving leader told the gathering. “I said we would prevent the establishment of a Palestinian state, and we are doing that, together. I said that we would build and hold fast to our land, our homeland, and we are doing it. And this is not the end – this is the beginning.”

Netanyahu's stance has shifted, given he appeared to embrace the prospect of a Palestinian state for several years. In 2011, he said in a speech to the US Congress that “a Palestinian state must be big enough to be viable, independent and prosperous.”

Recently, and especially following the 2023 attack by Hamas, he's abandoned that idea, arguing that the Palestinian movement is in the grip of extremists like Hamas, designated a terrorist organization by the US and many other governments.

At the dinner, Ganz told Netanyahu what he's been saying for years — Israel should extend its sovereignty over some 70% of the West Bank, leaving the rest for Palestinians to oversee basic services and the economy, with security in the hands of Israel.

In E-1, Arara, the Bedouin, was asked whether he believed the move to build more Jewish housing might somehow be stopped. No, he said. “This is a government of settlers.”

Essential Business Intelligence, Continuous LIVE TV, Sharp Market Insights, Practical Personal Finance Advice and Latest Stories — On NDTV Profit.