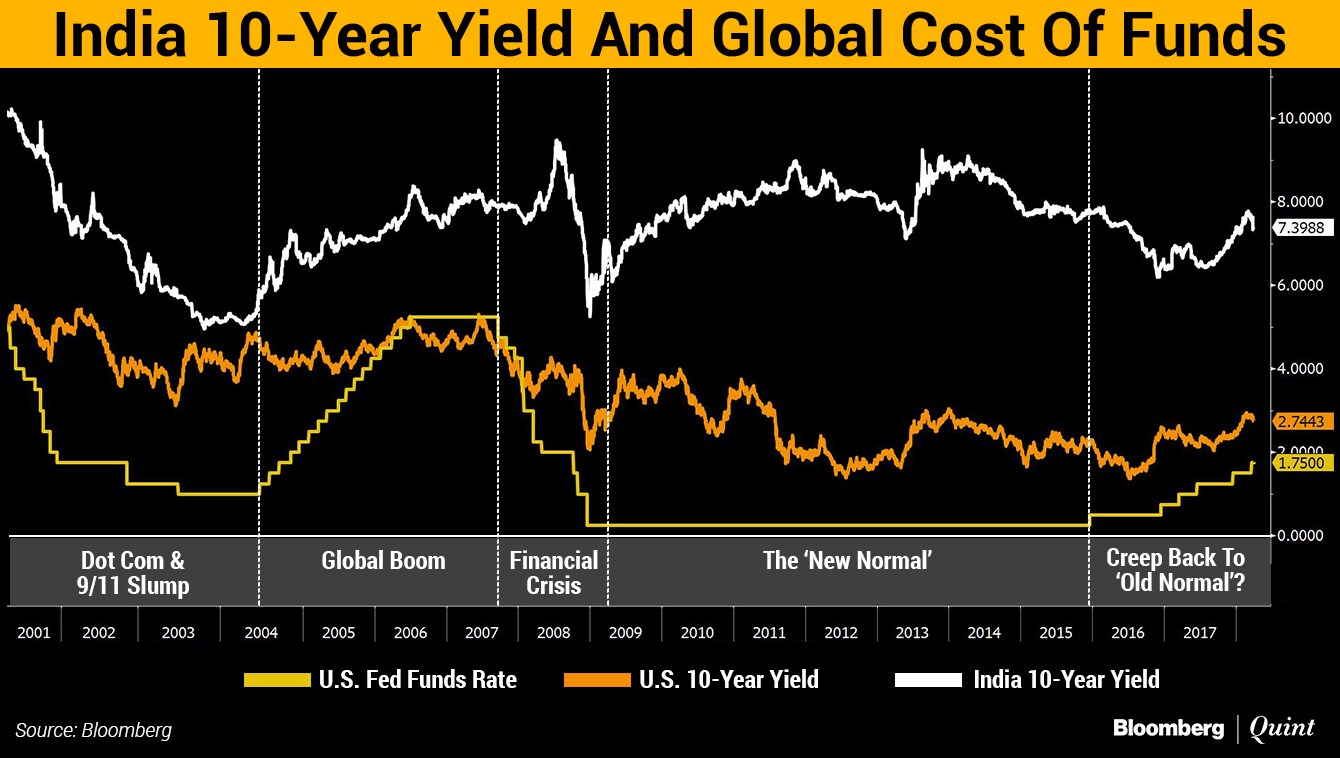

The United States Federal Reserve's overnight rate is currently at 1.50-1.75 percent, rising from near-zero in the fourth quarter of 2015 - nine quarters ago. The Fed is expected to raise rates three more times in 2018, and then twice in 2019. As per this guidance, the Fed overnight rate may be in the range to 2.75 percent and 3.00 percent by the end of 2019.

As such, a long-range, ‘normal', U.S. Fed rate is difficult to assign.

- During the period 1990-2000 the Fed rate moved between 3 percent and 6 percent, with the average being 5 percent.

- Between 1980 and 1990, the rate had swung wildly between 20 percent and 5.6 percent, averaging around 8-9 percent.

Each decade experienced different economic events and situations and ended up having a unique range of interest rates, which were difficult to predict at the start of that decade. Of course, on an ex-post facto basis there are explanations for these trends.

On the flip side, it is also difficult to see the Fed rate rising to 5-6 percent in next 5-7 years, in the absence of either a 2003-2007 like global GDP boom or surging global inflation.

Even a rise in the U.S. Fed rate to 3 percent has significant implications for Indian monetary policy, limiting opportunities for the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) to cut interest rates.

Also Read: The Two Ends Of India's Inflation Debate

Focus Shift From Domestic To External Front

In the last three years, the MPC focused on domestic inflation for determining policy rate as well as providing guidance. To the extent that the U.S. Fed rate remained at or below 1 percent for most of this period, and India continued to attract reasonable foreign capital—supporting a strong Rupee—the external sector did not present a significant risk.

While inflation looks broadly moving along an expected trajectory currently, the MPC's focus may shift to the U.S. Fed rate, and other associated external factors, as the driving consideration for Indian interest rates. India is a net importer of capital and goods/commodities. To the extent that the global cost of funds rises, trade and financing channels are likely to import the higher cost of funds to India, causing some amount of inflationary pressure. A more direct impact of a U.S. rate hike may be on global re-allocation of portfolios, in response to the higher cost of dollar funding. For starters, there may be potential reduction/or incremental limited investment in emerging markets including India. This, in turn, may put some downward pressure on the domestic currency.

This is not to imply that Indian interest rates have a straightforward direct correlation with the U.S. Fed rate. There can be scenarios where Indian interest rates do not increase or decrease despite the change in the U.S. Fed rate. These scenarios include an enhanced attractiveness/demand for Indian bonds under situations of significant improvement in the Indian economy and or government finances. That's when the risk premium and the liquidity premium on Indian paper reduces.

In the absence of such developments, a rise in the U.S. Fed rate would most likely lead to an increase Indian rates over next two-three years.

Also Read: How Much Longer In The Goldilocks Zone?

Lessons from 2000-2017

The last time the U.S. Fed rate moved from 1 percent to 3 percent was from mid-2004 to mid-2005, during a global boom. In the corresponding period, the yield on U.S. Treasury securities of 10-year maturity (U.S. 10-year yield) hovered around 4.0 percent to 4.5 percent. However, the yield on Indian Government securities of 10-year maturity (India 10-year yield) spiked in the same period by 175 basis points to hit 7 percent. During this period the RBI repo rate remained at 6 percent. In March 2004, the RBI reduced the repo rate to 6 percent from 7 percent. Even after June 2005, the Fed rate continued to rise and by August 2006, it plateaued at 5.25 percent. During the same period, the India 10-year yield rose by a further 100 basis points. The RBI got into the action in October 2005 with a 25 basis points repo hike, and by October 2006 the repo rate had risen to 7.25 percent. October 2005 marked the beginning of an interest rate hike cycle which peaked in August 2008 with a 9 percent repo rate.

The factors behind the upswing in the India 10-year yield were i) a rise in the global cost of funds, and ii) rising domestic inflation expectations in the backdrop of a roaring economy. Given the boom and resultant—if not always justified—high-risk appetite, corporate and bank growth continued despite rising interest rates.

Also Read: Inflation Relief, IIP Boost May Not Be Enough For Monetary Policy Panel

Between October 2016 and February 2018, the India 10-year yield shot up by 125-150 basis points, attributable to the enhanced volatility in recent times. In the corresponding period, the U.S. Fed rate increased by approximately 100 basis points. The U.S. 10-Year G-Sec Yield remained more rangebound.

The Rate Trajectory

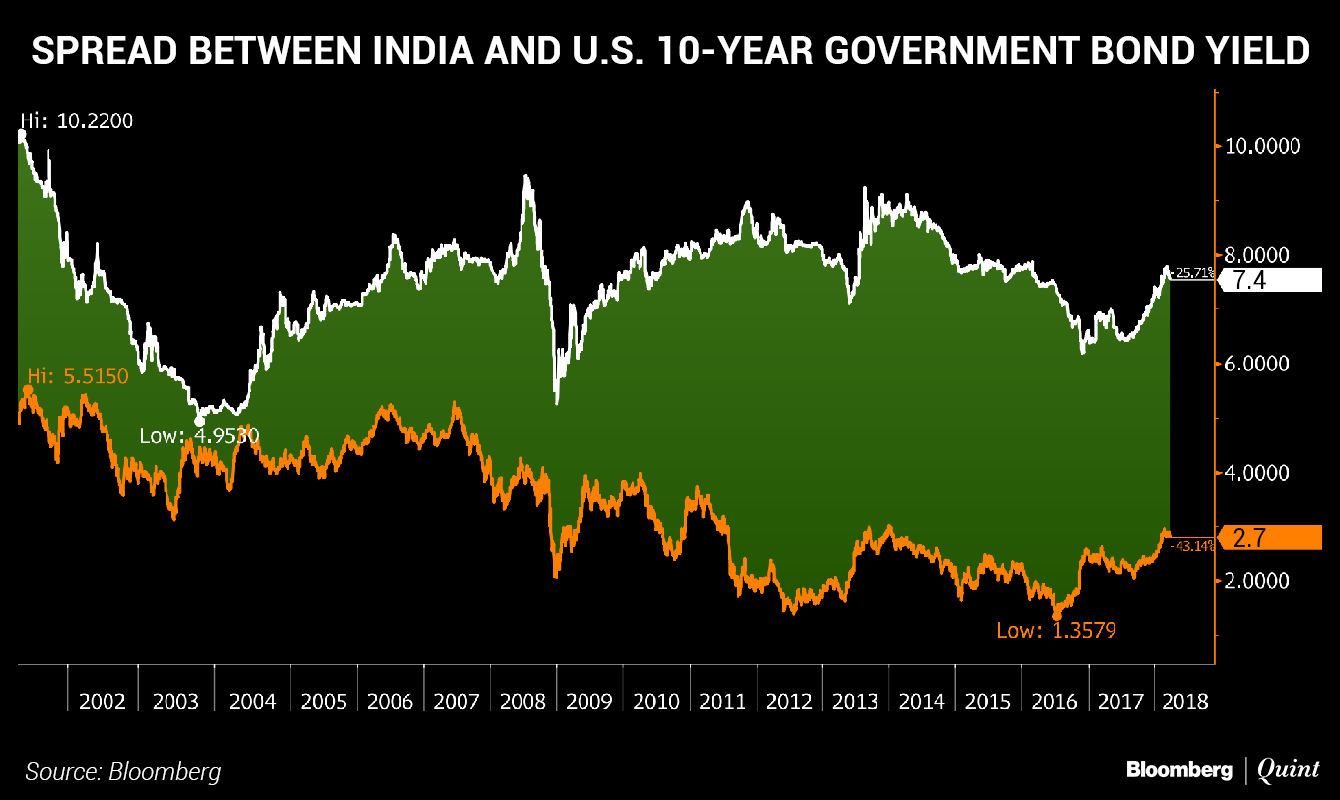

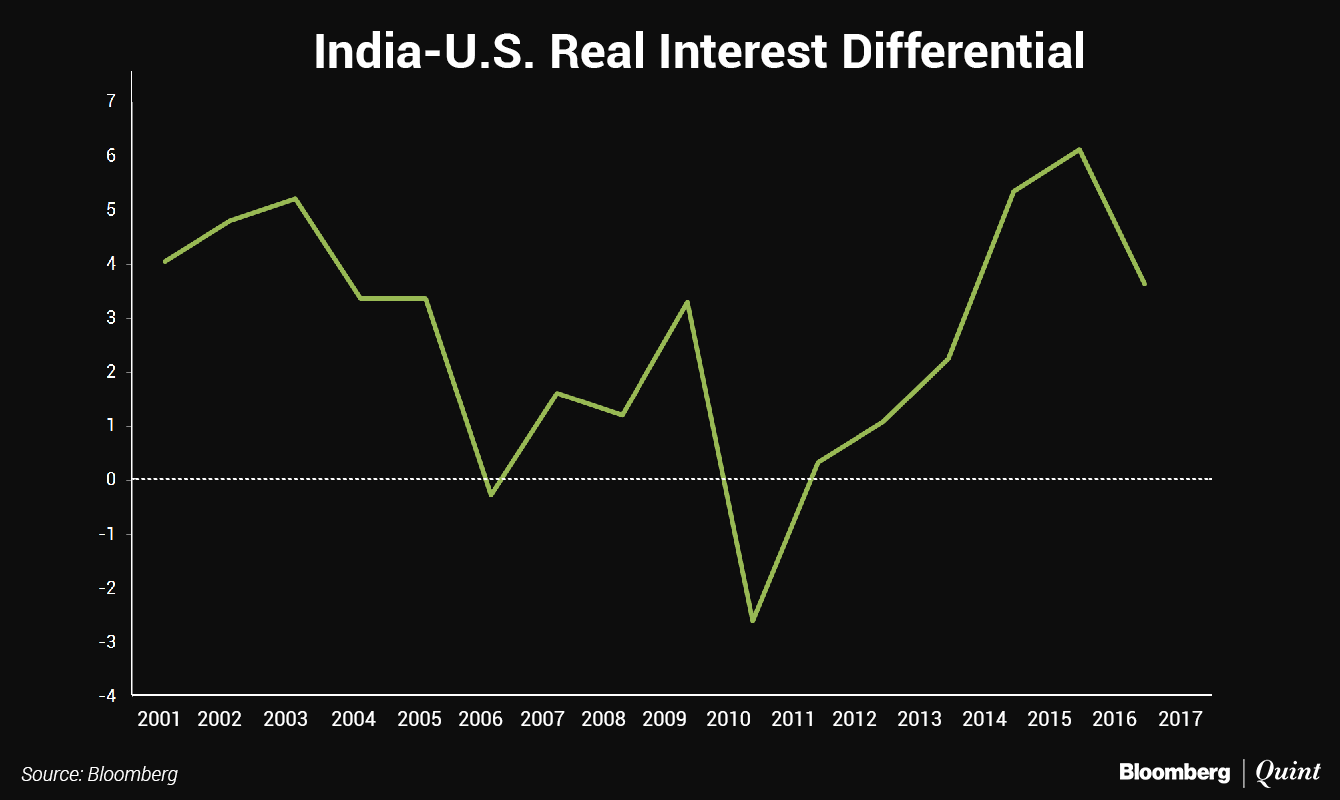

In the absence of an unanticipated slowdown in the U.S. economy or any other crisis, interest rates in the U.S. are likely to move up over next two to three years. To plot how interest rates may move in India, at the risk of simplification, we could use the historical real interest rate differential between Indian and U.S. rates as well as the historical spread between yields on India's and the United States' 10-year yield.

After the global financial crisis of 2008-09, the average spread has increased to a 5.5-6.0 percent range, from 3.5-4.0 percent in the pre-crisis period.

Meanwhile, the real interest rate differential has been in a higher range than the pre-crisis period.

If the U.S. Fed is moving towards a 3 percent rate by 2019, and simultaneously looking to nudge core inflation in the U.S. closer to its 2 percent target, we could expect the U.S. yield to move up as well. While there are many other factors that determine India's bond yield and, as a result, the central bank's policy rate, in the absence of dramatic improvement in India's fiscal and external position the range of the spread or risk premium to Indian government securities, over that of the United States, is unlikely to narrow significantly. Ceteris paribus (all other things being equal) a 3.5-4.0 percent U.S. 10-year yield in 2019 could mean that the India 10-year yield may be found in the range of 8.50-9 percent, from the current range of 7.25-7.75. A 50-75 basis points increase in the repo rate—as a proportionate response to a 75-125 basis spike in the yield over the next 7-8 quarters—may not be as far-fetched as it appears now.

Deep Narayan Mukherjee is a financial services professional and visiting faculty of finance at IIM Calcutta.

The views expressed here are those of the author's and do not necessarily represent the views of BloombergQuint or its editorial team.

Essential Business Intelligence, Continuous LIVE TV, Sharp Market Insights, Practical Personal Finance Advice and Latest Stories — On NDTV Profit.