(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The UK has become stagnation nation with gross domestic product per head falling for seven consecutive quarters. It puts the government in an even tighter predicament as contraction in the third and fourth quarters confirmed that the economy is in recession, destroying one of Prime Minister Rishi Sunak's five tests. The March 6 budget from Chancellor of the Exchequer Jeremy Hunt may introduce public-sector spending reductions to fund tax cuts, but with limited fiscal room for maneuver, he — and the economy — could do with some help from the monetary side of the equation.

The message from this week's economic data is pretty gloomy. GDP shrank by 0.3% in the final three months of last year, after a 0.1% contraction in the previous quarter. For all of 2023, the economy grew just 0.1%; more worrying is 1% compression in the private sector in the final nine months of last year. There's little sign of respite with ongoing public-sector strikes, and Bloomberg Economics expects a further 0.1% contraction in the current quarter.

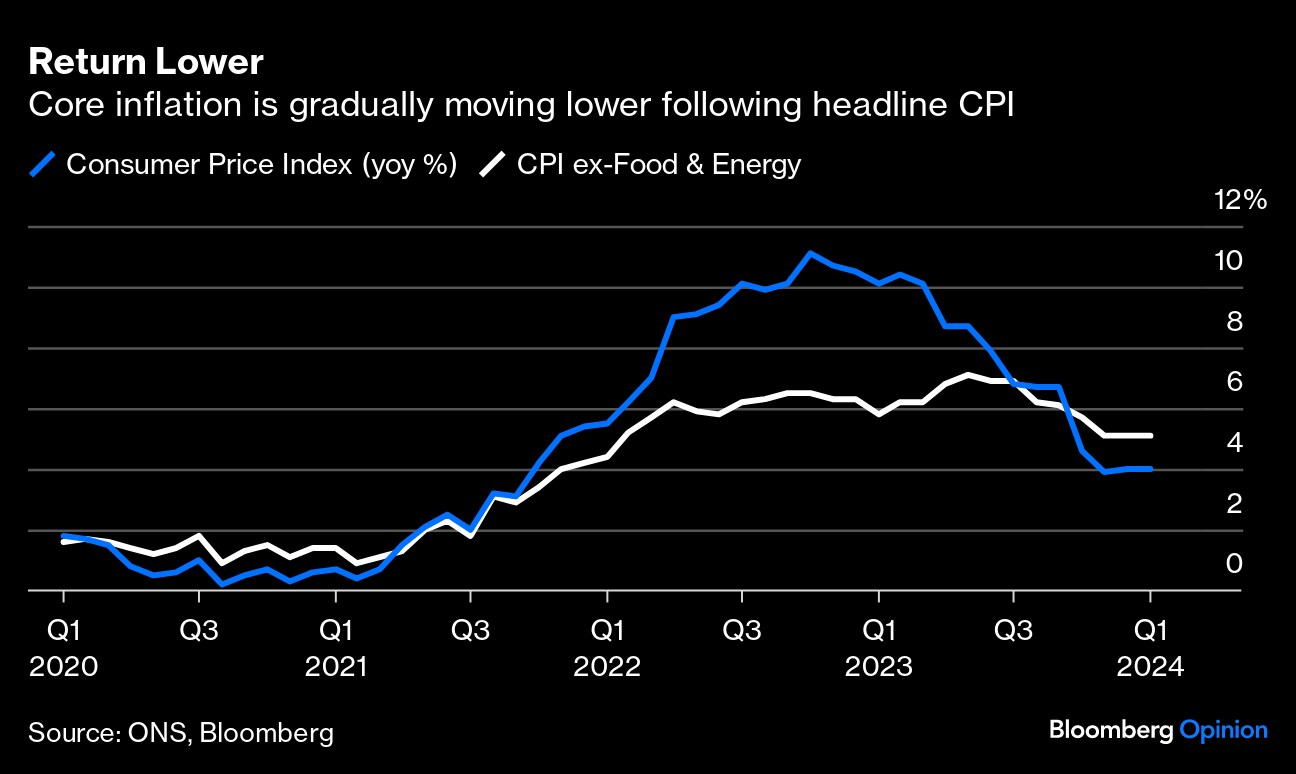

Inflation stayed at 4% in January, continuing the trend of consumer prices behaving better than the Bank of England had forecast, with core inflation also steady at 5.1%. The broader trend is unmistakably for slower price increases; while prices in the services sector prices did tick up one notch to 6.5%, that was also lower than estimates.

So far there's little evidence of cost-push inflation from the attacks on ships in the Red Sea. Food inflation slowed to a 7% annual pace from 8% previously. An even stronger signal is coming from food producer prices, which have stopped increasing and which typically lead supermarket prices by around six months. With drop of as much as 25% in energy prices expected due to the lowering of price caps in April and July, Bloomberg Economics expects headline inflation to fall below the 2% target this spring and head lower over the summer.

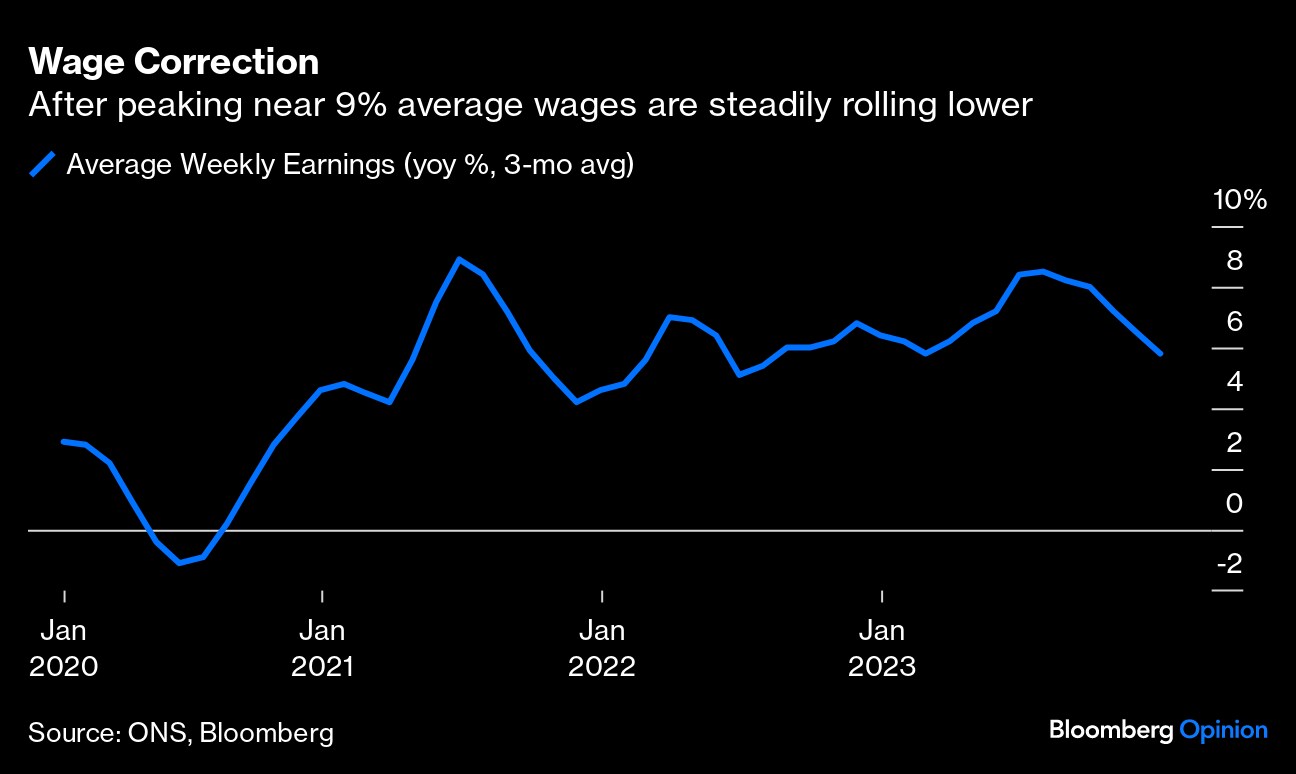

December's employment and wage data did blip above the BOE's February forecasts, but annualized wage growth of 5.8% was down from 6.5% in November, illustrating the downtrend has momentum. The respected KPMG/REC private-sector employment survey is flashing red, noting that "permanent staff appointments fell at a sharp and accelerated pace." Starting salary wage growth is the weakest for three years, while the overall pay survey is consistent with 3% pay growth, according to Bloomberg's Chief UK Economist Dan Hanson, who noted that it tends to lead official data by about nine months.

The quality of Office for National Statistics data is extremely patchy at present, with its labor-force survey still in reconstruction mode. A very low employment rate of 3.8% may not be sending accurate signals, with 22% of the workforce economically inactive. Several months of contraction in household consumption, which is highly sensitive to borrowing costs, is the most worrying aspect as consumer confidence remains very fragile.

BOE Governor Andrew Bailey downplayed the significance a mild recession in a speech on Monday. He says he sees signs of growth picking up — but he remains oblivious to the need to nurture those green shoots of recovery. Bailey, along with Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell, remains focused on the headline CPI rate as the lodestar for policy. Even after stressing at the Feb. 1 monetary policy review that "inflation is now falling rapidly. We are seeing evidence of this," in comments to the House of Lords Economics Affairs Committee on Wednesday Bailey reiterated that services inflation and wage increases are still too high for comfort.

But pressure is rightly building on the UK central bank to acknowledge the need to seriously consider a looser monetary policy than its current 5.25% official interest rate. Former BOE Chief Economist Andy Haldane told Sky News on Monday that he would have voted to cut interest rates at the end of last year. Real interest rates, after adjusting for 4% inflation, are the highest since before the global financial crisis and are set to go much higher which will crimp financial conditions further.

The earliest most economists expect any rate cut is at the next monetary policy review in May. This allows time to assess any new budget measures, and gauge the impact of wider pay-round effects, such as a 10% increase in the minimum wage.

What's important now for an economy dead in the water is that the central bank signals it will be easing monetary conditions in the not-too-distant future. Both the Fed and European Central Bank have stoked expectations for lower borrowing costs; after this week's economic evidence, the BOE is running out of excuses not to follow suit.

More From Bloomberg Opinion:

-

Inflation Selloff Is Wake-Up Call to Market: Mohamed A. El-Erian

-

First There Was Transitory. Now Comes Intransigent: John Authers

-

ECB, BOE Shouldn't Wait for Fed to Cut Rates: Marcus Ashworth

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Marcus Ashworth is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering European markets. Previously, he was chief markets strategist for Haitong Securities in London.

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com/opinion

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.

Essential Business Intelligence, Continuous LIVE TV, Sharp Market Insights, Practical Personal Finance Advice and Latest Stories — On NDTV Profit.