From Wall Street to Washington, tariffs have been the subject of much anxious conversation in recent weeks. As Americans debate the wisdom of the administration's on-again, off-again trade barriers — the latest was a threat issued Tuesday to double tariffs on Canadian steel and aluminium, now apparently in limbo — a few broad points are worth bearing in mind.

One is that these measures are a tax on Americans. Foreign countries don't simply pay up; US companies do when they import a product. This means that the costs are ultimately borne by consumers and by companies that use imported inputs. The effect of those higher prices is to eat into household budgets, push down real wages and reduce economic growth.

Even if voters were willing to tolerate higher prices, moreover, tariffs will likely mean fewer American jobs. All else equal, as costs rise, demand subsides. Lower demand reduces output, which leads to less employment. If other nations retaliate — as most are planning — the effects will worsen, meaning yet higher prices and fewer jobs.

Nor will such protectionism revive American manufacturing. Tariffs reduce competition, making it easier for domestic companies to skate by with worse products and less efficiency. In the emblematic case, duties imposed on foreign cars in the 1970s and 1980s blinded US automakers to the need to innovate — both in vehicle design and production — and allowed Japanese competitors to race ahead.

History offers plenty of other reasons for caution. A previous round of tariffs on steel and aluminum in 2018 raised producer costs and consumer prices, impeded exports, and resulted in about 75,000 fewer manufacturing jobs. Each job “saved” in the targeted industries cost some $650,000. A similar dynamic prevailed for President Barack Obama's 2009 tariffs on Chinese tires and President George W. Bush's 2002 steel tariffs.

The current administration's plans — including a 25% tariff on most goods from Canada and Mexico, also in limbo, plus a 20% duty on those from China — could prove especially costly. One study found that they'd amount to a tax of more than $1,200 per year for typical US households. Growth might be reduced by 0.4% or more. As many as 400,000 jobs are at stake. And that's not including plans for a 25% tariff on imports from Europe and new duties on agriculture, cars, chips, copper, lumber, pharmaceuticals and more.

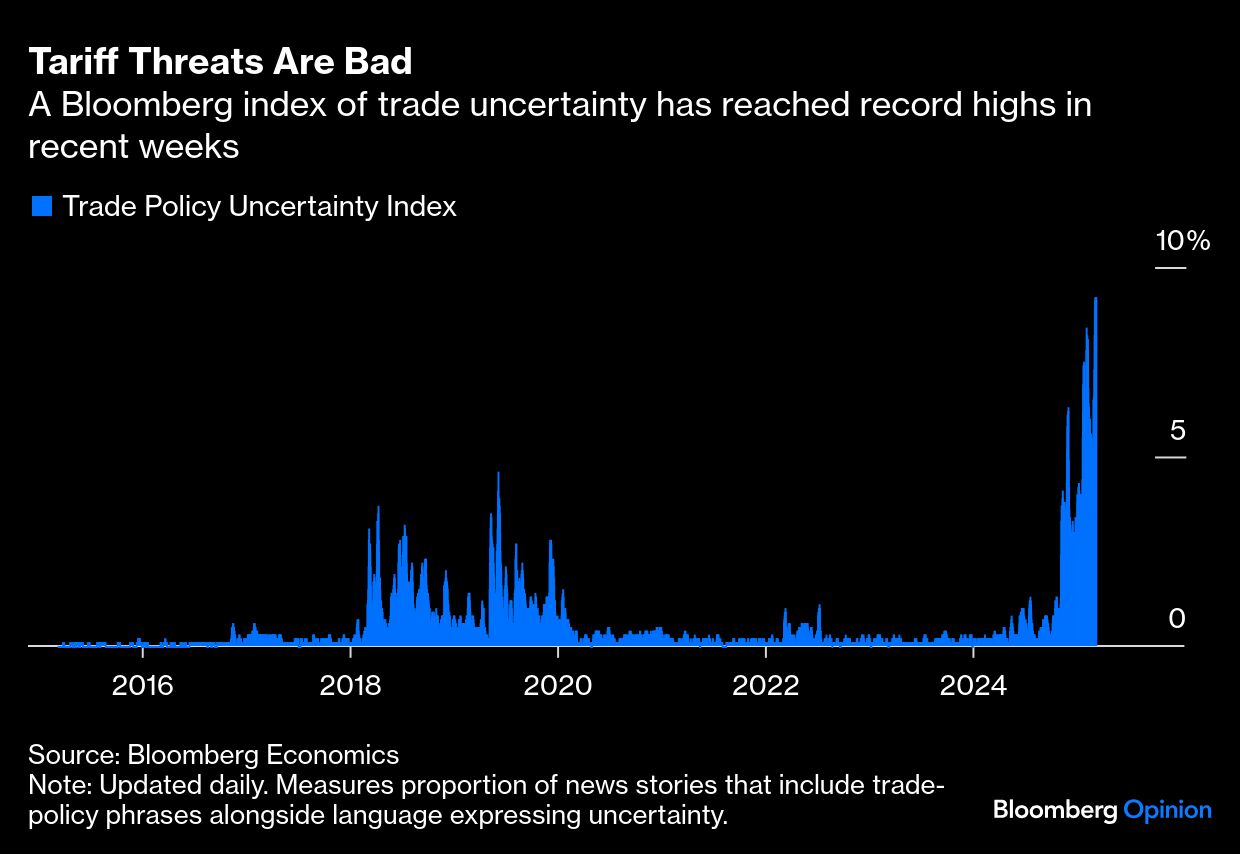

In addition to the immediate economic harm, these measures threaten to embroil the US in years of haggling, impose immense administrative costs, and further erode the rules-based global trading system that has facilitated broadly rising prosperity. The added uncertainty will only impede investment. That's to say nothing of the diplomatic damage caused by antagonising US allies.

More to the point: American companies should have nothing to fear from competition. The most successful US businesses didn't succeed because of tariffs. They succeeded by harnessing the entrepreneurial spirit, and by delivering better products and services at lower prices. Companies that demand protectionism are signaling that they can't compete without the government's help, which should be a big red flag.

Congress and the White House shouldn't be doling out favors to such companies. Instead, they should be adopting policies that incentivize investment and growth, encourage research and development, build a skilled and creative labor force, modernize infrastructure, and, yes, welcome more talented immigrants to work in the US and to start the next generation of great companies.

That's the American way — or, at least, it should be.

Essential Business Intelligence, Continuous LIVE TV, Sharp Market Insights, Practical Personal Finance Advice and Latest Stories — On NDTV Profit.