In a world worried about looming food shortages triggered by the climate crisis, the collapse in rice prices — now approaching their lowest in 18 years — is evidence that interventions by governments and modern agricultural methods may save the day. The key is productivity: more food from fewer farmers.

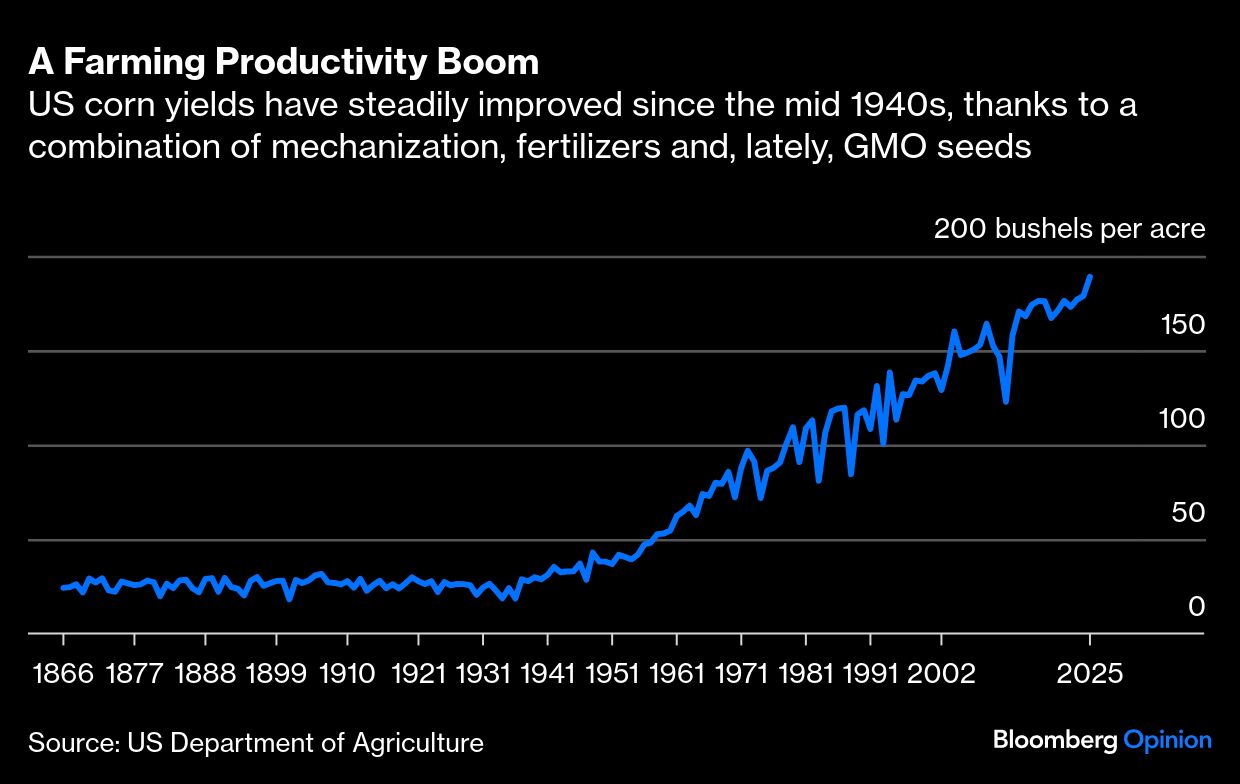

When we think about technological advances, what comes to mind are the internet, smartphones and now the arrival of artificial intelligence. But farming has enjoyed a dramatic and often overlooked productivity revolution: Over the last century, crop yields have exploded.

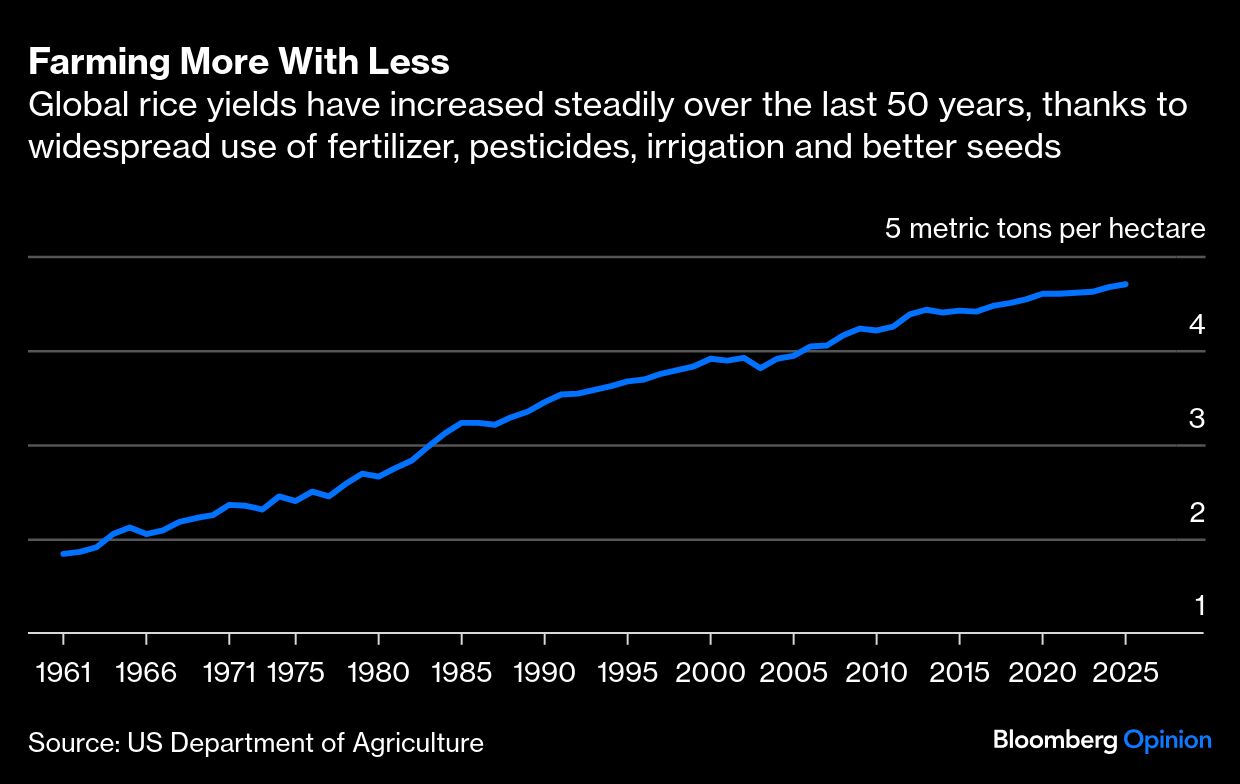

Rice is a great example. In 1975, farmers around the world harvested an average of 2.4 metric tons per hectare; the yield improved to 3.8 tons by 2000, and today it's almost doubled to 4.7 tons. Other crops, from corn to soybean to wheat, have also experienced massive gains, allowing larger crops even in more difficult climate conditions. And those gains can be sustained.

The corn market is also paradigmatic of our newfound ability to produce more food. For decades until the early 1940s, yields flatlined at about 20 to 30 bushels per acre. From 1945 onward, they've steadily improved, first at a rate of about one bushel per acre every year, and more recently at a rate of about two per year. This year, the US Department of Agriculture expects farmers to reap nearly 189 bushels per acre — a record, and double what was possible 50 years ago.

We're all benefiting from that little-known productivity boom: Without it, food prices would be significantly higher, and larger swathes of the world would regularly go hungry.

Still, opposition to modern farming methods keeps increasing, often accompanied by calls for a return to yesteryear's ways: A world with little mechanized farming, without fertilizers, pesticides, genetically modified seeds or irrigation.

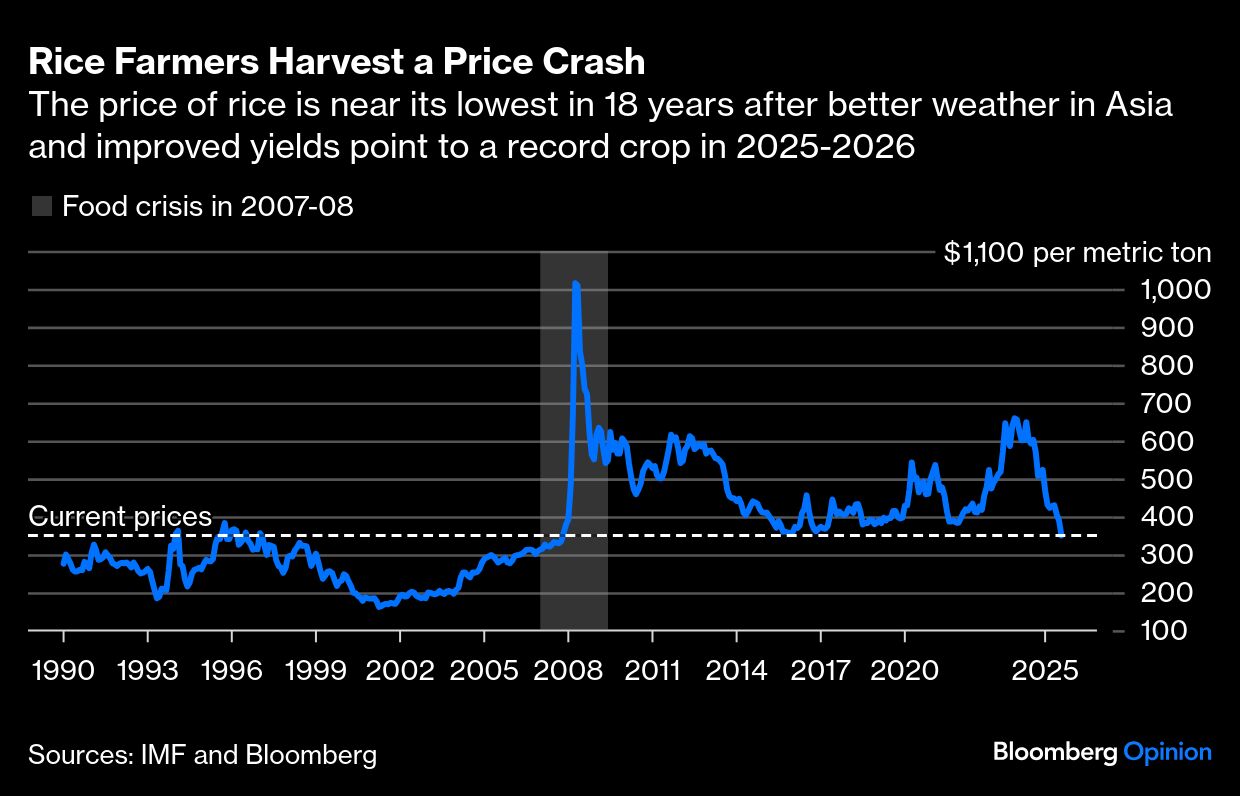

The benefits of government investments in modern farming are most evident in rice, the world's most important crop for food security. Even if largely ignored by investors and Wall Street, rice is a staple for half the world's population. Over the last four years, Asian and African nations had been on edge: A dangerous mix of bad weather, protectionism and panic buying fueled an inflationary spike in prices. In Asia, the grain has the potential to topple governments; national leaders watched with apprehension as the regional benchmark, Thai 5% white rice, surged to a 10-year high of $650 a ton by early 2024, up more than 60% from $400 a ton in mid 2021.

The concern was that prices could revert to the record high of more than $1,000 a ton seen in 2007-2008, when food riots spread from Bangladesh to Senegal to Haiti. Some feared that this was the new normal, due to the impact of climate change on crops. Certainly, the weather was at play; but rather than the climate crisis, the main culprit was the on-and-off El Nino weather phenomenon, which disturbs rain patterns in Asia. Worries that carbon emissions would make rice perennially more expensive proved overblown.

Now that rain has returned to most of Asia, modern farming is helping. The world will reap a record rice harvest of about 541 million tons in 2025-2026. For perspective, that would be double the crop of 1980-1981, while the amount of land in cultivation has changed little. No wonder prices are down.

The world — and Asia in particular — can do more to extend the productivity boom. The key is ensuring that farmers have plentiful access to credit, so they can invest in modern machinery, fertilizers and pesticides. Irrigation is also essential, and that demands public investment, which should also be channeled into research to improve seeds. Advances in agricultural genetics, which can create plants that tolerate both less rainfall and flooding, should be encouraged, not banned. Chinese scientists have completed trials of new genetically modified rice varieties that offer much hope; others in the region should do similar work.

With every technological advance, there are risks. Over-fertilization is one, but that can be tackled by educating farmers to adopt the best techniques. Meantime, GMO seeds pose risks to neither health nor the environment, in my opinion; they've been banned in much of the world for no good reason. In a 2010 report, the European Commission reviewed more than 25 years of scientific research on GMO, concluding that “biotechnology, and in particular GMOs, are not per se more risky than conventional plant breeding technologies." The United Nations World Health Organization has said that after several decades of GMO cultivation in several countries, "the consumption of GM foods has not caused any known negative health effects."

There's a final challenge: More productive farming ultimately means fewer farmers. And that's a good thing — Asia and Africa need more food, not more people working the land. Governments need to manage migration from rural areas to cities, from tilling the soil to being employed in industry or the service economy — the path to riches in America and Europe over the last 100 years.

As the price of rice shows, science can help the world to cope with the changing climate without going hungry.

Essential Business Intelligence, Continuous LIVE TV, Sharp Market Insights, Practical Personal Finance Advice and Latest Stories — On NDTV Profit.