Moody's Ratings has followed S&P Global Ratings and Fitch Ratings in stripping the US of its top-notch credit score, lowering it one level to Aa1. While it shouldn't really come as a surprise, history suggests that it augurs bond market volatility in the weeks and months to come, forcing us to wake up to facts we've been conveniently ignoring.

We can quibble about the direct causality, but bad things seem to happen when America's credit rating is being questioned. When S&P cut the US in August 2011, yields on 10-year Treasury notes initially jumped, but they ended up falling in the final assessment as the S&P 500 Index slumped and markets treated the episode as a “flight to safety” trade. In August 2023, the market impact was a bit less immediately obvious, though nonetheless insidious. As the Wall Street commentary highlighted at the time, we'd seen this before, and it was Fitch for crying out loud, a firm without the same pedigree as the others.

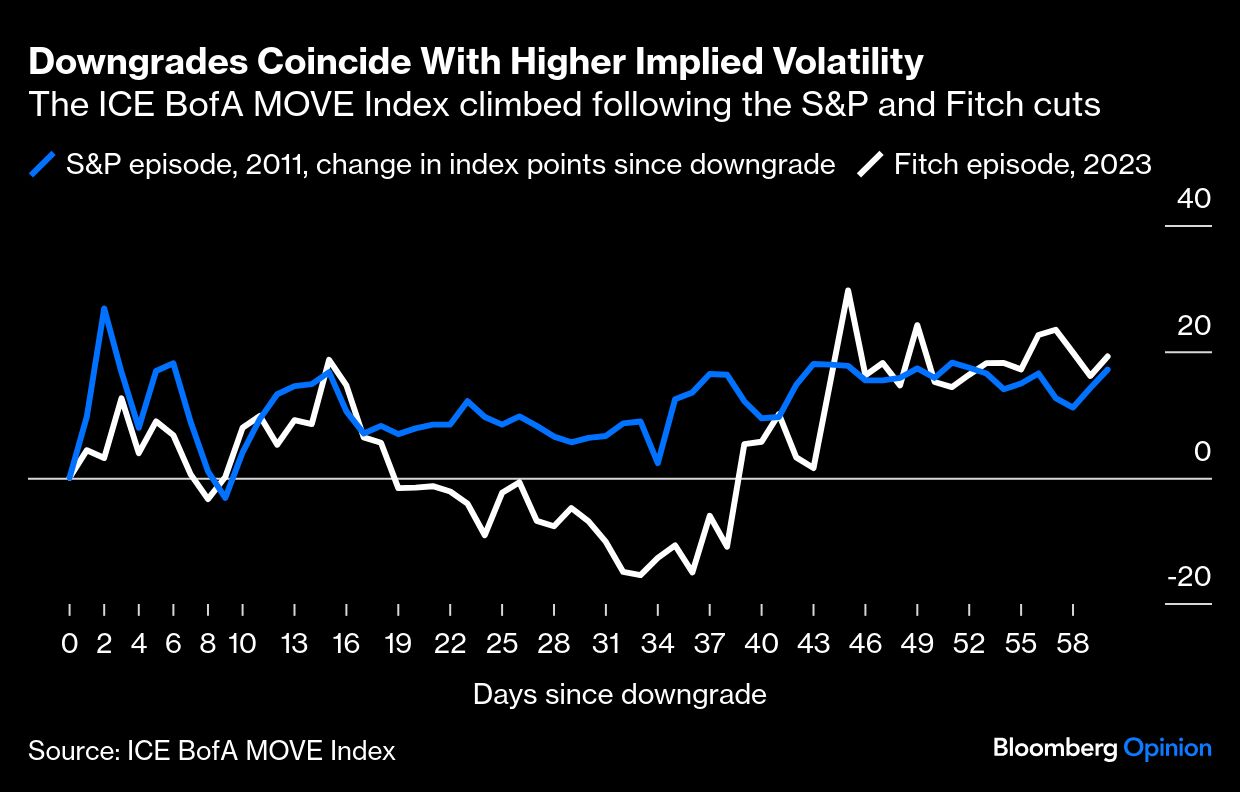

But the 2023 downgrade served as kindling for a fiscal conversation that had started early that summer, and 10-year yields would go on to climb about 103 basis points over the following 56 trading days, pushing them to their highest since 2007. Seizing the moment, billionaire Bill Ackman would go public the day after the cut with a bet against longer-term Treasuries. And the implied volatility of Treasuries, as measured by the ICE BofA MOVE Index, would actually climb a similar amount after the Fitch cut as the S&P one.

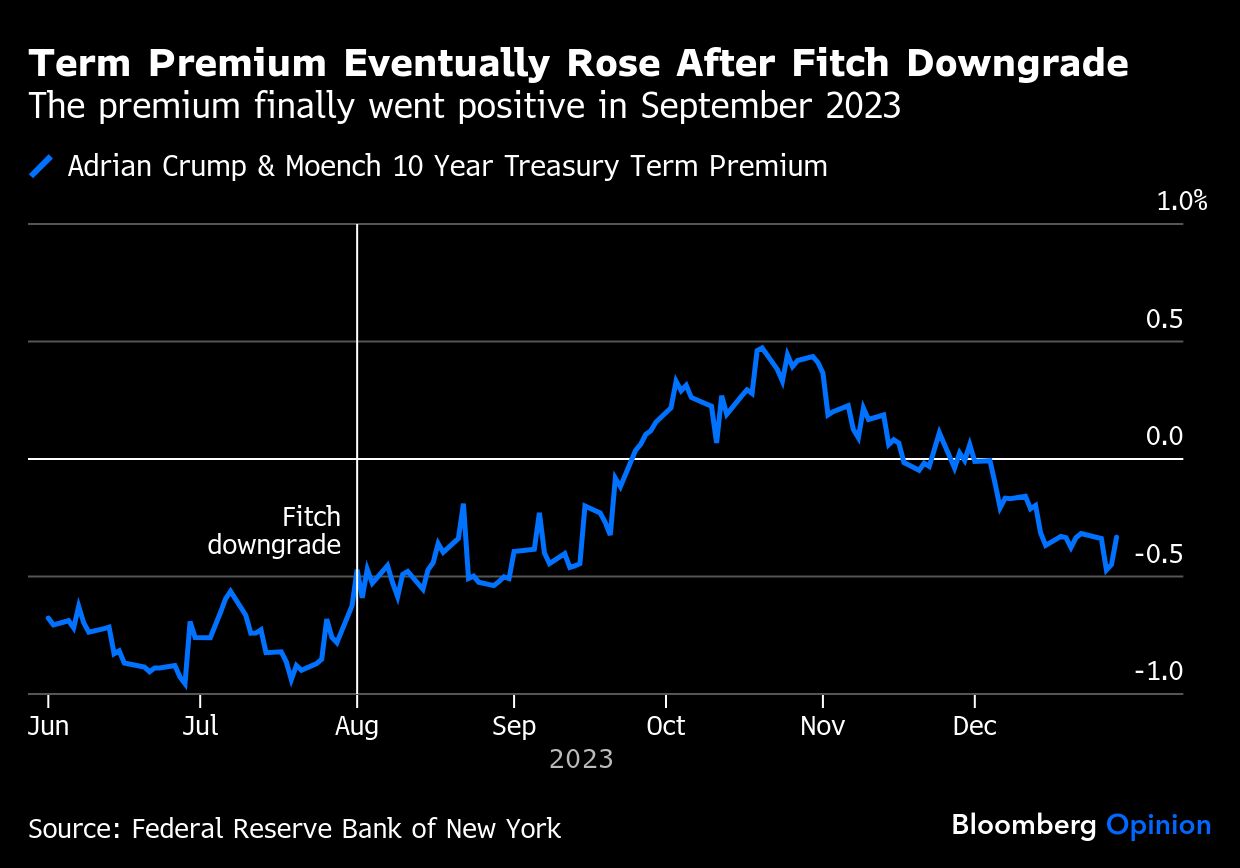

The question of causality is complex. While the early part of the 2023 selloff seemed to reflect a repricing of the inflation and monetary policy outlooks, the term premium would increase in the later months of the selloff. The Adrian, Crump & Moench version of the premium would turn positive in September, and fiscal concerns pretty clearly played a role. It was a perfect storm that Fitch had helped catalyze, and US 10-year yields rose much more than other developed markets such as Japan and Germany.

Part of the story, I suspect, is related to what economist Christopher Sims dubbed rational inattention — the idea that investors and other economic agents have finite time and attention and operate on an imperfect grasp of the facts. In a nutshell, we ignore a lot of information until we can no longer afford to do so.

In the case of federal debt and deficits, they've been large and growing for decades. Typically, investors ignore them in their day-to-day analysis of the market, and they've long been vindicated in doing so. After all, the stewards of the world's most important economy will always be able to pay their debts (as Alan Greenspan quipped, we can always print more money). For the foreseeable future, America should continue to find buyers at its bond auctions (where else are investors going to find debt markets this deep and liquid?).

Fixed-income investors are almost always better off using their time pouring over inflation and labor market data or trying to parse the umpteenth speech of the week from a voter on the Federal Reserve's rate-setting Federal Open Market Committee. In more recent times, they've also had to study up on global trade relationships (blame Donald “Tariff Man” Trump for that) and the legal arguments over whether the president has the authority to demote Fed Chair Jerome Powell (I hope not and don't believe that to be the case, but it could be a close call if the question ever makes it to the Supreme Court).

Clearly, US deficits do matter, just not in the way that they matter in other countries that don't have the world's reserve currency. If the US turns on the money printer, bond investors will pay for America's sins with more inflation. Ratings downgrades force us to think through those scenarios and, in the current context, refocus our attention on the fact that the US has accumulated a debt as large as its gross domestic product. At the moment, deficits are running at about $2 trillion annually, and Republican lawmakers are advancing a tax deal that wouldadd around $3.3 trillion to the debt through 2034, according to the Committee for a Responsible Budget.

Will America survive this? Of course it will, but that doesn't mean the developments can't jolt markets in the short run — and that it won't demand challenging adjustments in the medium term. Remember: the market has mostly been ignoring the situation for years. Think of a student who has been daydreaming in class for the past 20 minutes and suddenly hears his named called by the teacher. It can be startling! Perhaps the Moody's downgrade is just one small part of that awakening — perhaps even more of a symptom than a cause.

Admittedly, the volatility could also play out as it did in 2011, with yields counterintuitively dropping in a flight to safety trade. Unlike 2023, borrowing costs confront these developments from a relatively high starting point, especially given risks to the labor market. But the fiscal debates ongoing in Congress stand to keep the public's attention on the matter for weeks to come. And at least in the short run, the transition from daydream to reality is likely to shake markets as it has each time this happened in the past.

Essential Business Intelligence, Continuous LIVE TV, Sharp Market Insights, Practical Personal Finance Advice and Latest Stories — On NDTV Profit.