Economic activity as measured by gross domestic product (GDP) is a critical input in most monetary and fiscal policy-making processes. Like most other economic projections, GDP too is imperfect, but as long as it enables comparing economic activity across time periods it facilitates policy making. On January 31, 2017, the same day as the release of the much-celebrated Economic Survey 2016-17, the Ministry of Statistics and Program Implementation published revised estimates of GDP for past the five years – from 2011-12 to 2015-16.

The revised GDP data presented a significantly altered picture of economic growth over the last five years.

Confusion Due To An Altered Past?

When an individual or a group of people take a decision, they do so with the information they have at hand at that moment. So while it might be a tad unfair to judge the merits of a policy decision in hindsight, sharp revision in economic data does make one wonder if the course of action would be the same, had policy makers known then what we know now.

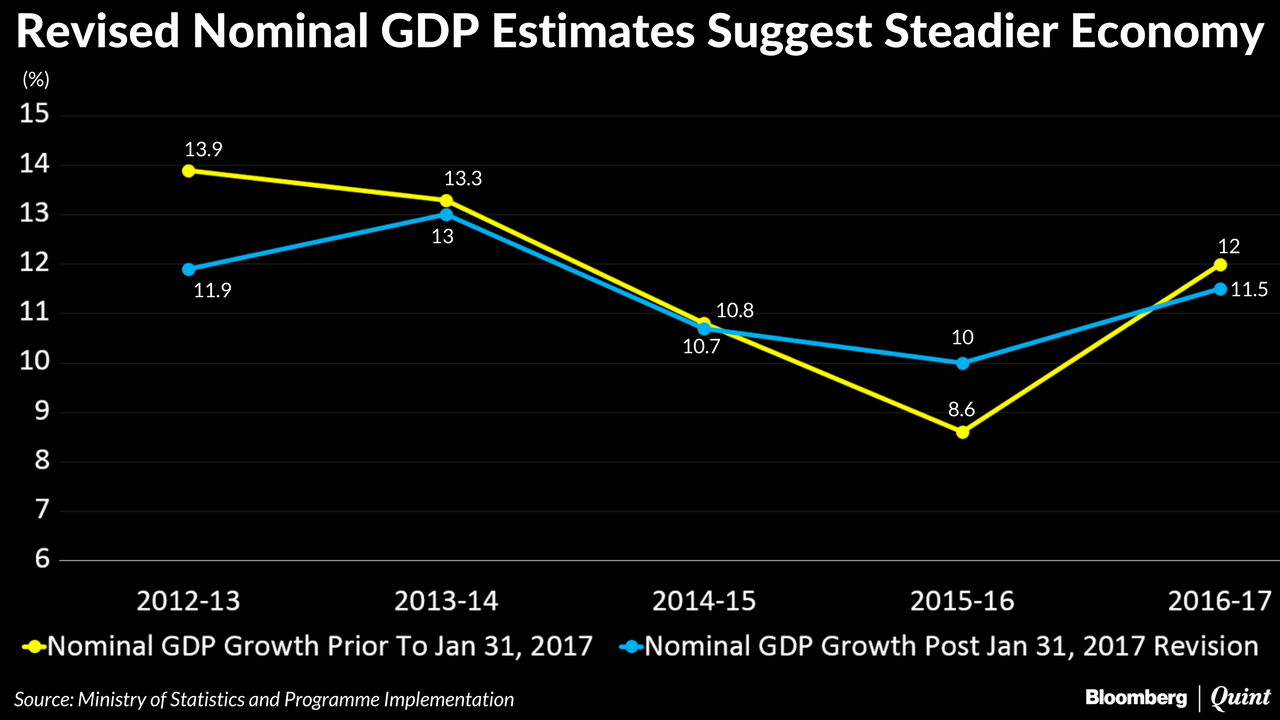

For instance, between January 2015 and October 2016, the Reserve Bank of India reduced its headline repo rate by 1.75 percentage points or 175 basis points. Previous estimates suggested that India's nominal GDP growth was falling sequentially from 13.9 percent in the financial year 2012-13 to 8.6 percent in 2015-16. Against this backdrop, the reduction in interest rates had been much in demand.

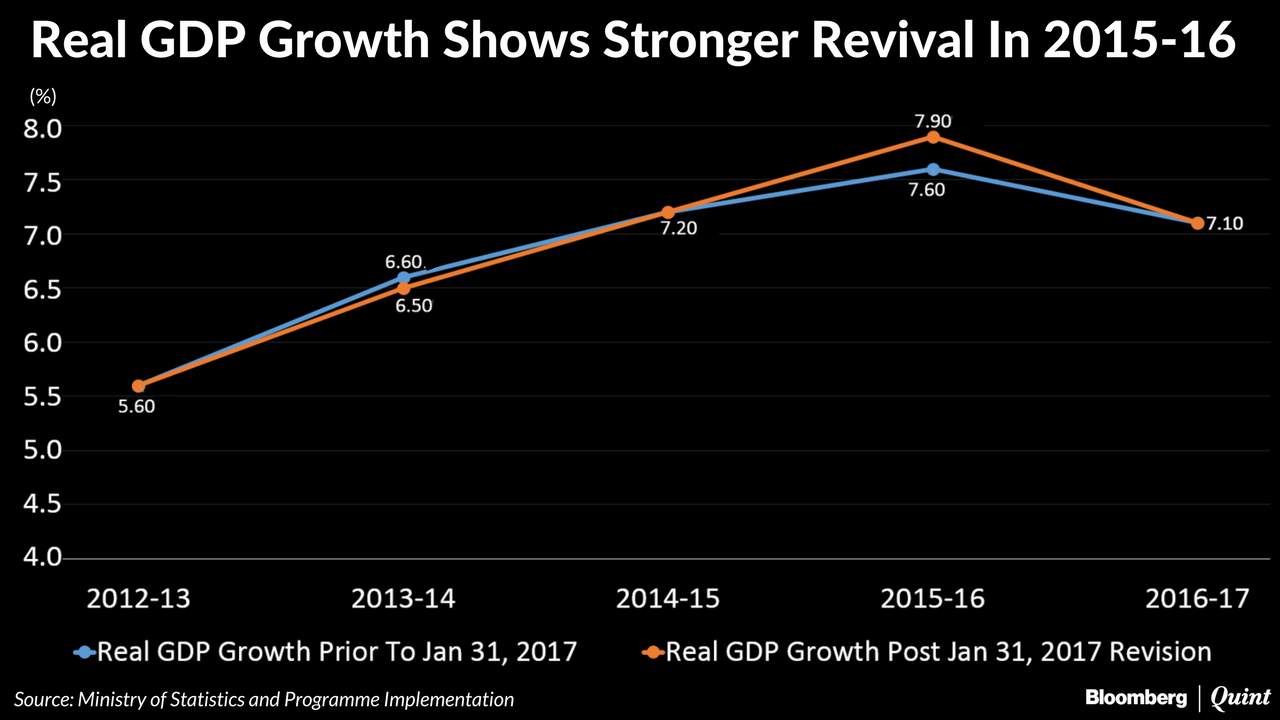

However, revised GDP estimates released in January now suggest that nominal GDP growth was 10.7 percent in 2014-15, and bottomed out in 2015-16 at 10.0 percent. Real GDP growth, it now appears, actually turned the corner in 2015-16 at 7.9 percent, from 7.2 percent in 2014-15.

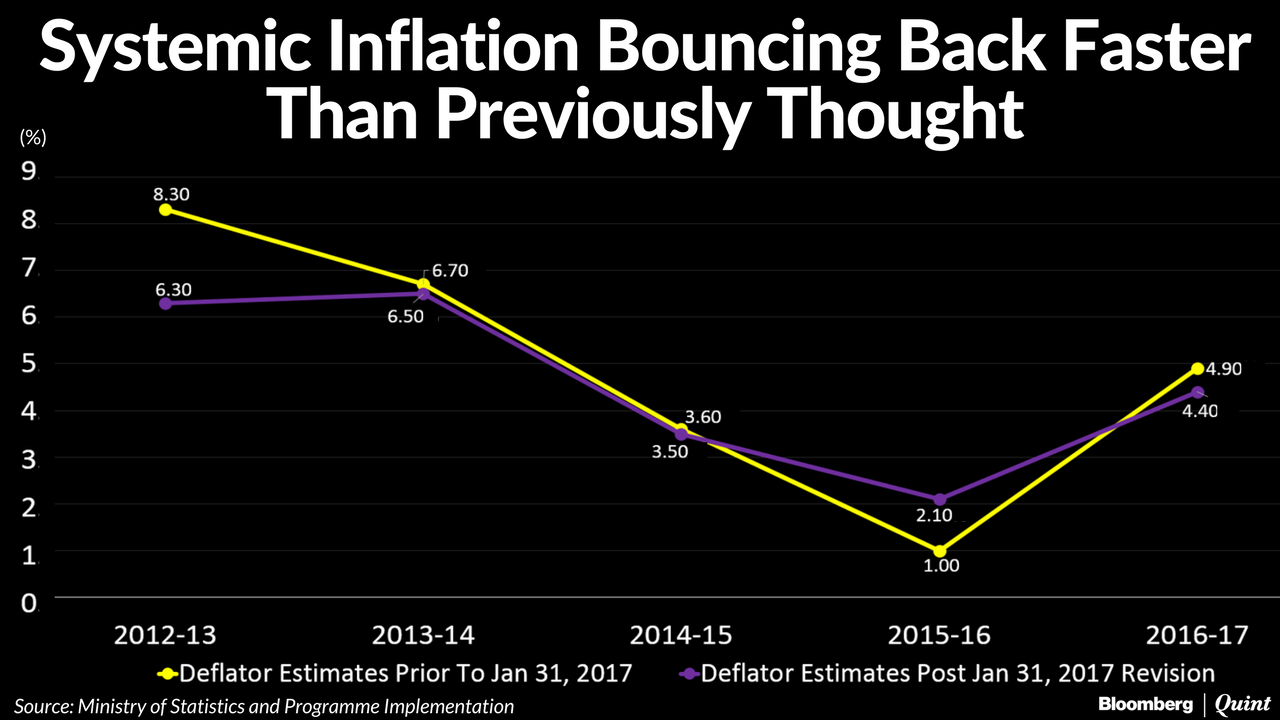

More troubling may be conclusions about systemic inflation or implied deflation. Typically, nominal GDP based on current prices is estimated first, and then deflated with inflation estimates to get real GDP.

As per the revised estimates, inflation was higher than initially thought in 2015-16. As the revision points to a bounce-back in growth and inflation, was the last rate cut in October 2016 really needed?

GDP estimates for 2012-13 to 2014-15 were revised downward, for some years by over Rs 1 lakh crore, while the estimate for 2015-16 was revised upward. The revised data alo seems to show that concerns about India's fiscal deficit were unnecessary, with the revised nominal GDP growth in 2015-16 being almost aligned to budgetary expectations.

Caution! More Revisions Coming

It's likely that India is not through with its GDP revisions. Monetary and fiscal policy mandarins may be dealing with volatile data all the way till 2019.

GDP revisions are not unique to India. This is the outcome of a process that is followed globally. The GDP measure, even for past periods, has significant dependency on the outcomes from statistical models. GDP is a ‘semi-probabilistic' estimate, which in the course of time gets revised, as new data arrives, or as statistical models get updated.

However, in India's case, the wait is as long as 5 to 7 years, to get a solid GDP estimate, because of a significant gap in the availability of critical data.

The problem is not with high-frequency data such as the Index of Industrial Production (IIP), quarterly results of listed companies, or trade data which is made available monthly or quarterly. The problem lies with data inputs which are dependent on survey outcomes. The latest revision was driven by the availability of the final results of the Annual Survey of Industry 2013-14. The survey suggested that 2013-14 was among the worst years for the economy in recent history, and provisional results for 2014-15 suggested marginal improvement in industrial performance.

Statisticians are now waiting for the results of the National Sample Survey Office (NSSO) survey on household expenditure for 2016-17, likely to be published in 2018. The current GDP estimates continue to depend on the last survey which was conducted in 2011-12 and published in 2013. This input has a significant bearing on estimating private final consumption expenditure which is 55-60 percent of India's GDP.

When the next NSSO survey results get incorporated into the GDP estimates which would then be released in 2019, the entire set of GDP numbers from 2012-13 to 2017-18 are likely to get revised.

What if we discover in 2019 that the economy was performing below potential but little was done to revive it because the available estimate suggested top-of-the-world, China-beating growth?

Also Read: The GDP Is A Flawed But Magical Indicator

Does India Need Its Own Li Keqiang Index?

A U.S. state department cable leaked by Wikileaks in 2010 quotes the current Chinese Premier Li Keqiang saying in 2007, when he was the head of China's north-eastern Liaoning province, that he monitored three data points – electricity consumption, rail cargo volumes, and loan growth points – to get a better sense of economic activity than what China's GDP data showed. This informal gauge was soon adopted by a number of China-watchers.

Likewise, it may be prudent for India to monitor macroeconomic factors that are more directly observable.

This index could serve as a proxy for GDP, to support policy decisions till the GDP measurement infrastructure is revamped.

Issues With The Base Year

Had the GDP revisions resulted in a parallel upward or downward shift in the growth rate, it would have been less confusing for policy makers. The January 2017 revision, however, revised GDP downward for 2012-13 to 2014-15, and higher for 2015-16. This suggests that there may be inflection points and structural breaks in the data. That in turn can perhaps be tracked back to the choice of base year and the out-of-phase data availability around the base year. 2011-12, it seems now, turned out to be an inflection point in the Indian economy, from high growth of previous decade to lower growth of the current decade. When the series was launched, models used to estimate GDP continued to depend on pre-2011-12 data.

As more data started arriving post 2011-12, the upwards bias got corrected, and the revised GDP came down.

Without going into whether 2011-12 was an optimal choice as the base year, there's still a comparison to be drawn on whether the data had settled enough before the latest GDP series was launched.

- The series with 1999-2000 as the base year was launched in 2006.

- The one with 2004-2005 as the base year was launched in 2010.

A gap of five to six years between the base year and the launch of the series allows for more information to come in, based on which various statistical models are updated or rebuilt. The 2011-12 series, launched in January 2015 did not allow for this.

Better Data For The Statistical Models

To correct this now, the next base year can be aligned with the year that the next NSSO Household Expenditure Survey is published, since that data will play into the estimates of private consumption, the largest component of India's GDP. Subsequently, more resources could be allotted to carry out the Annual Survey of Industry annually from its current publication once every two years. The five-year gap in the household survey could also be reduced. As such, the method of GDP estimation does not need to change, it is the quality of data input into that process which needs to improve.

Deep Narayan Mukherjee is a financial services professional and visiting faculty of finance at IIM Calcutta.

The views expressed here are those of the author's and do not necessarily represent the views of BloombergQuint or its editorial team.

Essential Business Intelligence, Continuous LIVE TV, Sharp Market Insights, Practical Personal Finance Advice and Latest Stories — On NDTV Profit.