Imagine your two friends, Ram and Shyam. Ram is rich — earns in crores, has taken loans twice his income, but seems cool all the time. Shyam is not that rich — he earns in lakhs, splurges a lot, and owes about the same amount as his income, which makes him panic when he sees the credit card bill.

Now, as for you, your income matches Shyam's, you have even lower debt than your income, but still, your parents nag you for getting another home loan.

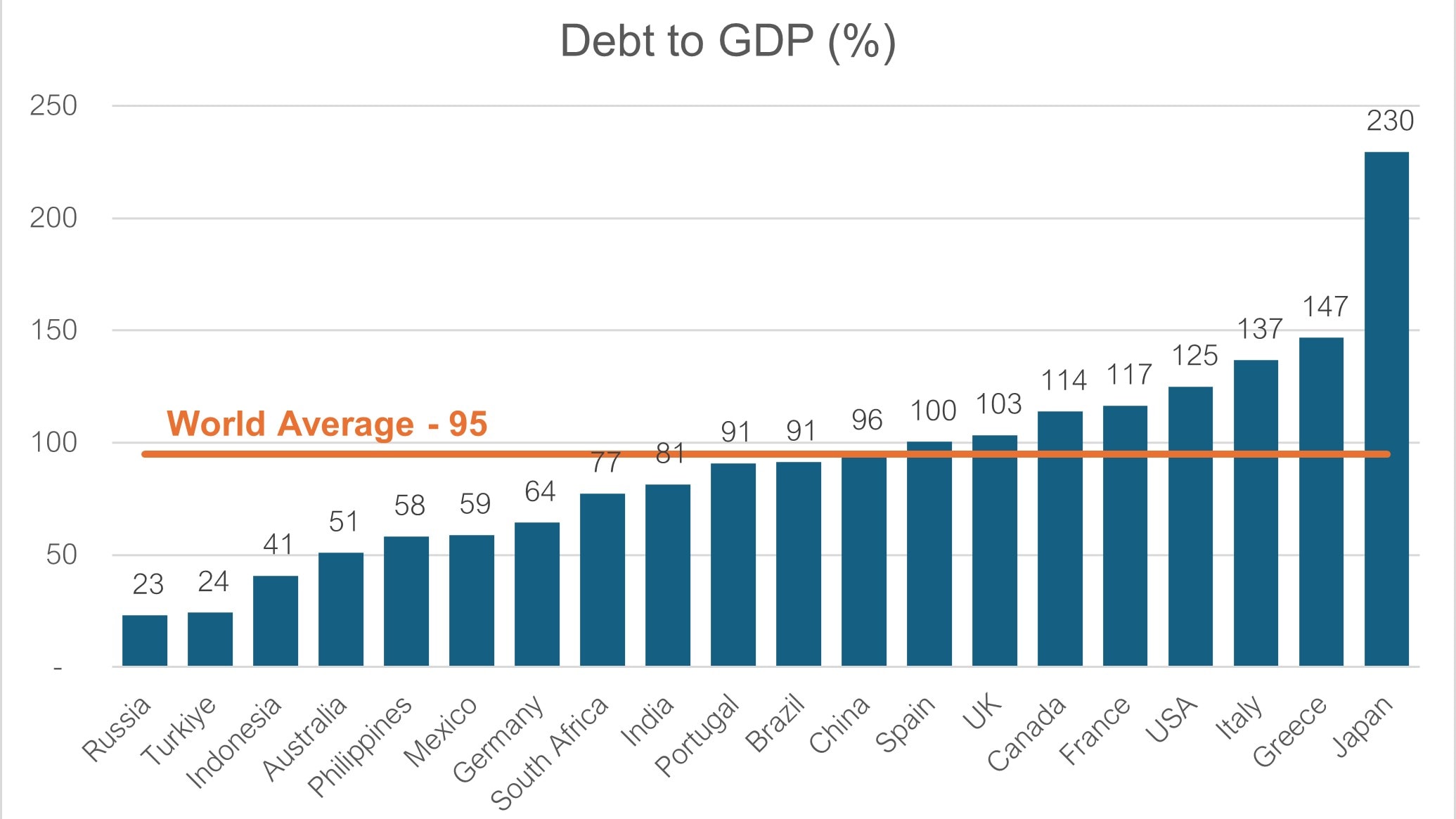

Countries behave exactly like these friends. Ram is much like Japan, still maintaining a debt of more than 200% of its GDP for a decade. Shyam is like Greece, while you are like India, receiving scoldings from rating agencies despite having a stable economy.

Myth Of 100% Threshold

Let's zoom out for a moment. This year, global public debt touched $110 trillion, representing around 95% of the world GDP. Half of it is owed by the US and China combined.

The debt-to-GDP ratio is higher for the developed countries, with the US at 125%, the European Union above 80% and Japan at 230%. Emerging markets, on the other hand, seem better, averaging about 73%, with India (83%) and China (88%) on the higher side.

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook (October 2025)

Whenever people talk about the debt-to-GDP ratio, 100% becomes a kind of sacred level — they believe that something like that should not have happened in the first place. Yes, it adds more pressure on the treasury. But it is odd to assume you and I could borrow more than our incomes, but the countries supposedly cannot. The IMF says that a country's repayment ability matters more than any ratio.

Simple Math Behind Debt Sustainability

Here's a simple check. Let's bring your friends back. Assume the interest rate on all loans is 5%. But Ram's salary increases by 10% every year on average, while Shyam's just 2%. Obviously, Ram is in a better position than Shyam. Similarly, if the economy grows faster than the interest rate, the ratio falls because of a larger denominator.

Then, there's another check: the primary balance, the difference between the government's income and expenses, excluding interest payments. It tells us whether the government can pay interest from its current year's income. If income is higher, then the government can relax. Otherwise, a deficit means the government borrows to cover even the interest cost. A moderate deficit is still manageable if the economy grows faster than the interest rate, but it can be painful otherwise.

And when neither works, governments resort to a simple hack: inflation. Inflation reduces the value of loans (the numerator) and boosts the GDP (the denominator), which makes the debt-to-GDP ratio smaller without any actual payments.

Savings — Quiet Side Of Same Coin

Governments borrow by issuing bonds. Corporations, institutions and people across the world buy those bonds through their savings. That's why debt and savings are two sides of the same coin. For the last 40 years, the world has had ample savings largely due to a large mass of baby boomers, the world's largest savers and trade surpluses of Asian countries. Therefore, interest rates stayed low for a long time. Even inflation was under control, thanks to cheaper goods from China. Together, that helped governments.

But now the tide is turning. Recently, household savings rates have dropped in many major countries. For example, Japan's rate has decreased from around 10–15% to just 3–4%, and the US has seen a similar fall from 8–10% to 3–4% in the last three decades. A lesser savings pool or a resurgence of inflation could push interest rates up, making debts costly. Therefore, we see politicians getting angry with central bankers for not keeping interest rates low.

An ageing population across the world, strained US-China relationships, the waning role of the US dollar, rising multipolarity, and slow economic growth all changes the way we save and the governments borrow in the future.

Future Of Debt

The most effective action is to bring deficits down. But low growth and rising burden of healthcare, social security, climate action and defence expenses leave little room. In the era of high debt and loose fiscal policies, politicians avoid taking difficult decisions, such as cutting unproductive expenditure or increasing taxes.

In the end, markets, and not the politicians, draw the line. Investors demand much higher returns to compensate for the rising risks. For instance, during the debt crisis in Greece, the 10-year government bond yields touched 40%, from 3–4% pre-crisis. The story may change this time, but the lesson doesn't: adjust now with some pain or later with more enduring pain. The 'too much' moment arrives when the trust fades.

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of NDTV Profit or its affiliates. Readers are advised to conduct their own research or consult a qualified professional before making any investment or business decisions. NDTV Profit does not guarantee the accuracy, completeness, or reliability of the information presented in this article.

Essential Business Intelligence, Continuous LIVE TV, Sharp Market Insights, Practical Personal Finance Advice and Latest Stories — On NDTV Profit.