For most people, monetary policy feels like a simple, rom-com kind of story. When the central bank cuts the interest rate, loans become cheaper, businesses and consumers spend more, and the economy grows. Well, that's the kind of happy ending story every textbook likes to tell us.

But like every Abbas-Mastan thriller, monetary policy has hidden layers and twists — and cheap money, almost every time, ends up behaving differently than the typical script. The current scenario in India is a perfect case study.

Businesses Don't Borrow Just Because Rates Fall

Firms don't invest because interest rates are lower. They invest when future demand looks strong.

At present, the capacity utilisation of India's manufacturing sector is around 76%. It means that a steel factory producing 76 tonnes out of 100 tonnes of capacity can meet the demand without expanding. Bank of Baroda's research concludes that utilisation rates need to hit 80% for firms to start new investments. So when the economy is not running in full steam, a fall in interest rate from, say, 10% to 9% doesn't change corporate decisions.

In fact, sometimes businesses may interpret aggressive rate cuts as signs of distress, making them more cautious.

The Transmission Twist

Just because the central bank headquarters has announced rate cuts doesn't mean that the loans have become cheaper in our nearest branches.

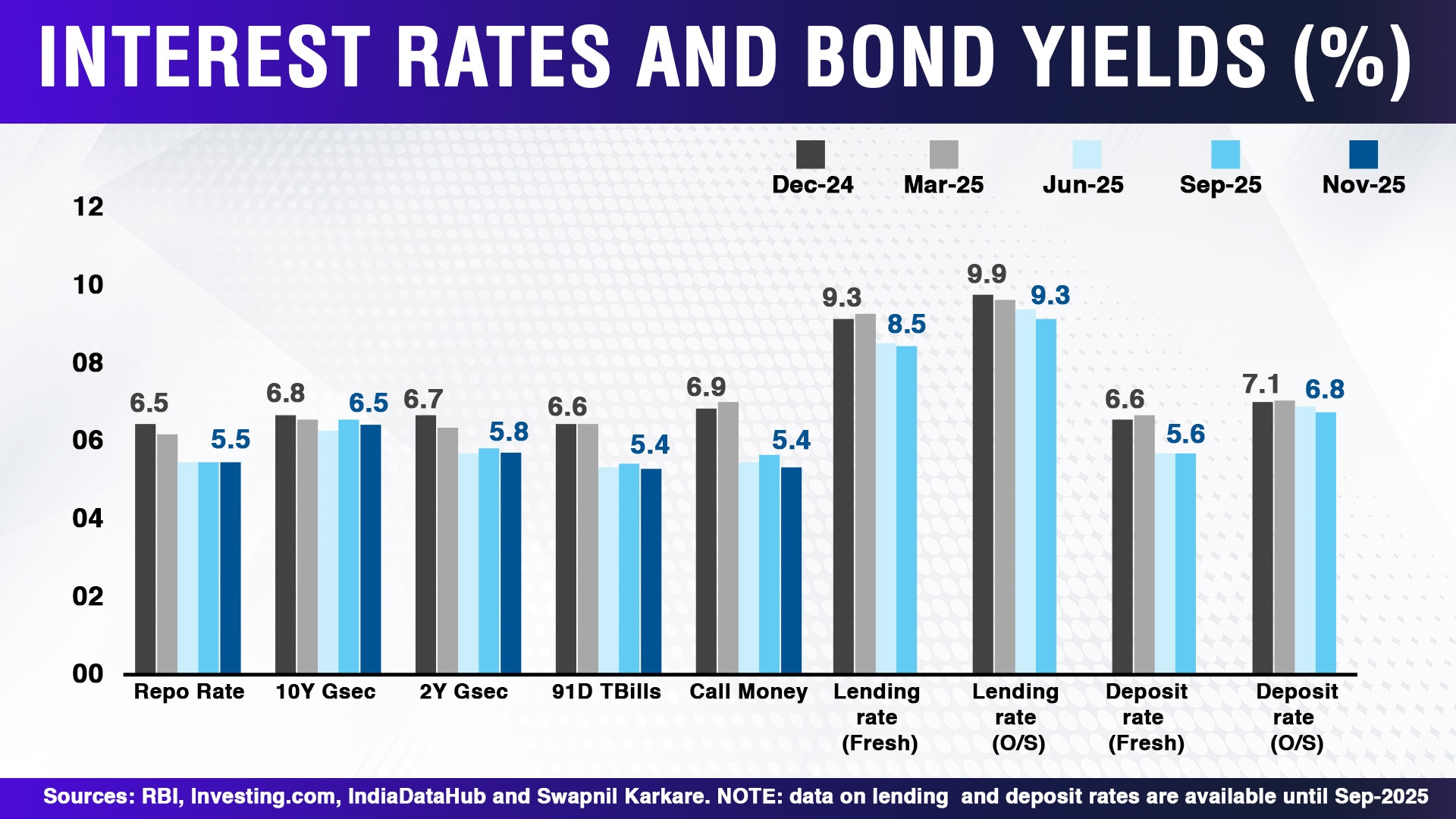

Despite the RBI's 100 bps rate cut this year and unusually low retail inflation, interest rates on loans and long-term bond yields have not fallen much. Long-term bond yields guide banks in setting their interest rates on loans. Bond markets demand higher yields because they expect higher inflation and more government borrowing in the near term.

Then, banks are worried about their margins. Banks have cut deposit rates due to surplus liquidity, but haven't lowered lending rates. Thanks to higher bond yields, they can earn better and safer returns from investing in government bonds than by lending. This has kept our home-loan and corporate-loan rates high. As long as bond yields are elevated, rate cuts are ineffective on the ground.

Businesses are repaying old loans instead of taking new ones

There's another twist. Sometimes, rate cuts trigger the opposite of what we expect. Instead of borrowing more, many firms are repaying their existing loans, with the extra cash flow from lower interest rates.

In FY25, more than 300 Indian companies turned debt-free. Moreover, the cash on their books had doubled by the end of the year. They are sitting on a cash pile of over Rs. 14 trillion as of September 2025, up by 12% from a year ago.

Cheap money keeps weak firms alive

Cheap money can also weaken an economy's potential and productivity.

Bank of International Settlements research shows that when interest rates are low for a longer period, banks don't force struggling firms to fix their problems. Instead, they keep rolling over credit. The practice is called forbearance.

The labour and capital that could have been used elsewhere more productively get stuck in such companies, pulling overall growth down. This ‘zombie-firm' problem has been observed mainly in advanced economies and even in India post-2008 financial crisis.

What if the RBI cuts the rate again?

I believe low inflation and weak demand warrant a rate cut, and the RBI has some room left, too. But considering the above factors, its effect is uncertain.

For instance, if long-term yields stay high despite another rate cut, the ground reality would remain more or less similar.

Then, there's rupee too. The interest rate gap between India and advanced economies has narrowed from the historical average of 5% to 2%. More rate cuts would make India less attractive for investors at a time when the demand outlook is also uncertain. It might trigger capital outflows, putting more pressure on the already fragile rupee.

That said, rate cuts aren't pointless. Lower rates reduce EMIs, giving breathing room for everyone. It is useful in a slowing economy and global uncertainties.

But when the demand is low, cheap money flows into assets such as equities, properties, and gold, and increases speculation rather than productive investments. In such a scenario, asset prices move up, but not the economy.

Final take

Just like movies need a strong supporting cast, cheap money, the hero of the story doesn't work in isolation. The movie looks good when everything aligns well: high confidence in the economy, strong balance sheets, and a higher risk appetite of banks. Until then, excess money may flow into financial markets, strengthen the cash position of large companies, or worse, be parked with the RBI itself, without boosting economic growth. That's not the ending we rooted for, right?

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of NDTV Profit or its affiliates. Readers are advised to conduct their own research or consult a qualified professional before making any investment or business decisions. NDTV Profit does not guarantee the accuracy, completeness, or reliability of the information presented in this article.

Essential Business Intelligence, Continuous LIVE TV, Sharp Market Insights, Practical Personal Finance Advice and Latest Stories — On NDTV Profit.