Markets naturally see through the lens of businesses. When tech stocks took a dive last month on concerns of an “AI winter,” investors were egged on by a study showing 95% of corporate AI pilot programs failed to deliver any gains in productivity or profit, making all this expensive AI start to look a little useless.

Consumers would beg to differ.

While businesses grapple with how best to plug generative AI tools into their systems (as they've naturally done with every other technology wave in history, from PCs to smartphones to social media) individuals have been embracing the technology. The phenomenon is easy to overlook when you only measure success with quantifiable metrics like time and money, and when the cost of running data centers is still so high. But some of AI's biggest winners so far are companies who are chasing squishier value propositions like entertainment and camaraderie. A study by Harvard Business Review earlier this year found that the three most popular use cases for generative AI were therapy and companionship, organizing life and “finding purpose.”

Character.ai's roughly 20 million monthly active users are on its platform for role-playing with AI-generated characters. It's on the cusp of breaking even on the cost of running its AI models—its so-called inference costs—which is an impressive milestone for any AI startup. A year ago when the company was still being led by its founder, former Google researcher Noam Shazeer, a large proportion of Character.ai's capital spending went on the cost of renting data centers and AI chips, in large part because Shazeer had grand ambitions to build AI models that were smarter than humans, so-called artificial general intelligence.

But Shazeer returned to Google earlier this year for an eye-watering $2.7 billion, and under new management, Character has focused on becoming an entertainment platform. Instead of only building its own AI models, it uses those of other companies like OpenAI, and its compute costs have now halved. Revenue from its $9.99-a-month subscriptions has grown to nearly match the $4 million it spends each month on inference, or the cost of generating AI content for its users. The app currently shows small banner ads but will likely introduce advertising in a more sophisticated way in the next year or so, turning on a potentially enormous revenue spigot.

OpenAI will eventually do the same. In May, it hired Fidji Simo, an executive that helped transform the delivery app Instacart into an advertising powerhouse. And last week, the company announced it was spending $1.1 billion on Statsig, a product-analytics company that helps consumer apps like Notion, SoundCloud and Linktree test new features, helping them hone which to keep or ditch. Expect OpenAI to use that new testing ability to introduce advertising to its platform.

OpenAI's purchase of Statsig reminds me of Facebook's 2013 acquisition of Onavo, a mobile-data analytics that helped it gather intelligence on mobile-usage trends and potential competitors, ultimately steering Mark Zuckerberg toward his $19 billion purchase of WhatsApp. Statsig could also end up working quietly behind the scenes to guide OpenAI to monetizing its all-important consumer base.

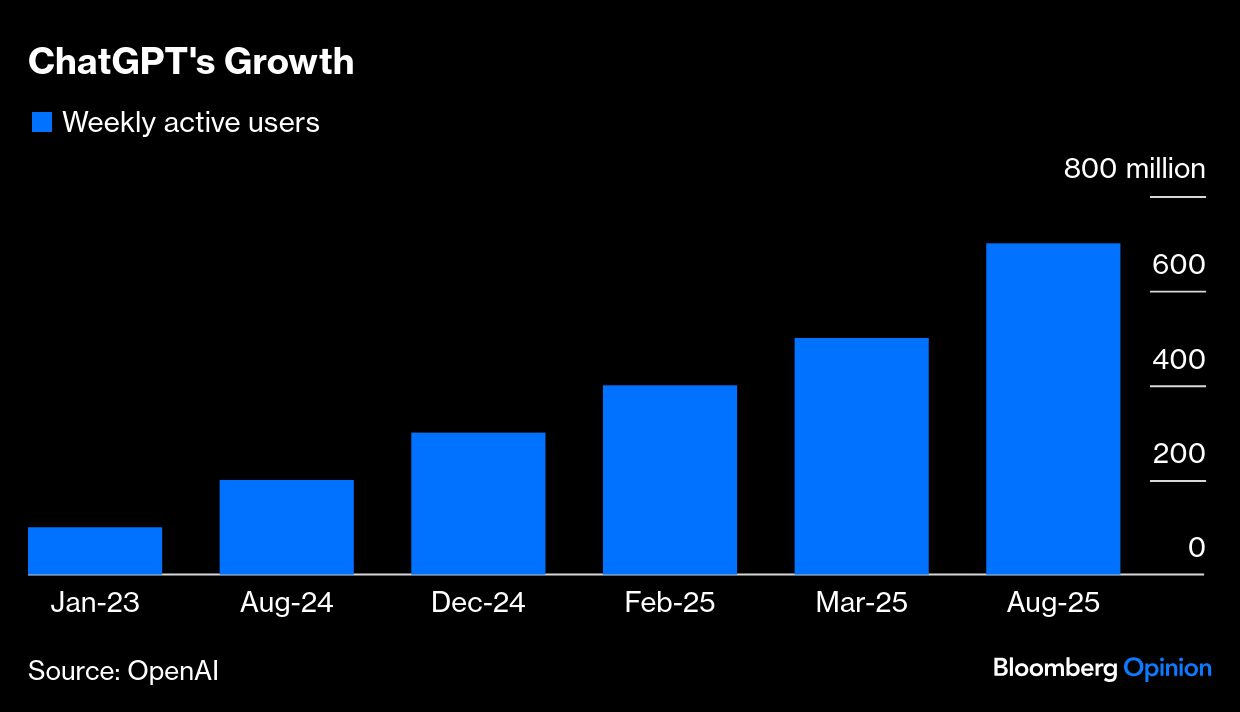

Despite OpenAI's enterprise ambitions, it is ultimately a consumer business. In less than three years, ChatGPT has amassed more than 700 million weekly users and some 99% of them are individual consumers using free and paid versions of ChatGPT. Roughly 5 million are business or enterprise customers of the company, which says it will make $13 billion in revenue over the next year.

For all the talk of corporate disappointment with artificial intelligence, the most important story may be happening at the individual level. Millions of consumers are already spending their own time and money on tools that entertain, organize and even console them. That shift points to an industry where monetization will come increasingly from subscriptions and advertising—just as it did with gaming companies and social media businesses—and where the firms best positioned to thrive are those willing to build for feelings as much as for efficiency, and who can capitalize on the model infrastructure being built by the likes of OpenAI and Google. If Wall Street still sees only an “AI winter,” it's missing the spring that's already underway in personal AI.

Essential Business Intelligence, Continuous LIVE TV, Sharp Market Insights, Practical Personal Finance Advice and Latest Stories — On NDTV Profit.