From Bourbon Street to Food Banks, Signs of a Slow U.S. Recovery

The U.S. economy is being reshaped, taking its time to heal and threatening to leave permanent scars.

(Bloomberg) -- What exactly does the Mall of America, with enough space for nine Yankee Stadiums, look like without throngs of Midwestern shoppers? Or Bourbon Street in New Orleans free of revelers? Or breadlines in the teeth of an economic meltdown?

These are the kinds of questions the 2020 pandemic raises about hubs of tourism and consumer spending, particularly those built on models that need big crowds.

So Bloomberg News teamed up with Orbital Insight, a California-based company that uses satellites, drones, balloons and mobile-phone geolocation data to track what’s happening on the ground. (Orbital has received funding in the past from Bloomberg Beta, a venture-capital unit of Bloomberg LP.)

By counting phone signals in 15 designated areas each day for the past three months, the data offer a way to see how many people are returning to where they eat, play and spend money — at mega malls, upscale retail streets and nightlife hotspots. Golf courses are humming again, but so are the nation’s non-profit food banks, underscoring the gap between the haves and the have-nots.

The picture that emerges is not of a V-shaped recovery, but of an economy that’s being reshaped, taking its time to heal and threatening to leave permanent scars.

Like a Hurricane

Months of home confinement have left many Americans itching for a night out at the bars, or maybe a getaway to one of those cities where whatever happens there stays there.

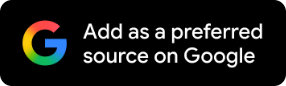

Such is the allure of Las Vegas, Nashville and New Orleans. But pedestrian traffic in the main nightlife districts in the three cities ranges from just 15% to 44% of year-earlier levels, according to Orbital’s phone tracking data. Along Bourbon Street in New Orleans, restrictions have induced a relative calm along the touristy strip of the French Quarter notorious for crowds with to-go cups of red slushy drinks.

“It feels like there’s a hurricane that’s supposed to land today or tomorrow,” said Brittany Mulla McGovern, executive director of the French Quarter Business Association. “We just don’t have anybody and people are just prepping to not be here for a while.”

The Drive to Tee Off

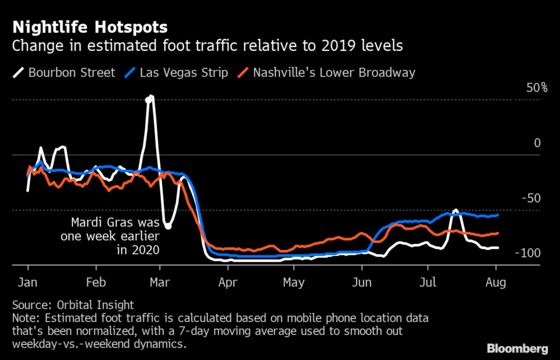

The pandemic hit U.S. golf courses in the northern half of the country at the least bad time — the winter off-season. So when lockdowns started to end as spring arrived, the links were among the first tests to see if people would return to public places.

According to the data monitored at three prestigious courses, two of them — private clubs at Cypress Point in Pebble Beach, California, and Pine Valley in southern New Jersey — look to have returned to year-ago levels, according to Orbital’s data.

Back to normal isn’t yet the reality for Mike O’Reilly, golf operations manager at Kohler Co.’s Whistling Straits, just outside Sheboygan, Wisconsin. This was supposed to be the year he welcomed one of the sport’s biggest international spectacles. Instead of helping oversee operations for the 2020 Ryder Cup, which was postponed until September 2021, he’s focused more on bringing in local clientele because of the air-travel downturn.

O’Reilly said Whistling Straits is running about 75% of normal for this time of year, buoyed by marketing aimed at players within a day’s drive rather than jet-setting corporate types and the bucket-list crowd. That’s possible because it’s part of a resort that’s open to the public.

Golf is a natural fit for social distancing so O’Reilly is optimistic. Plenty of duffers are taking up the sport, buying equipment and heading to public courses. “Play may be down a little bit at some facilities but play is really up overall at a lot of facilities,” he said.

Frenzies at Food Banks

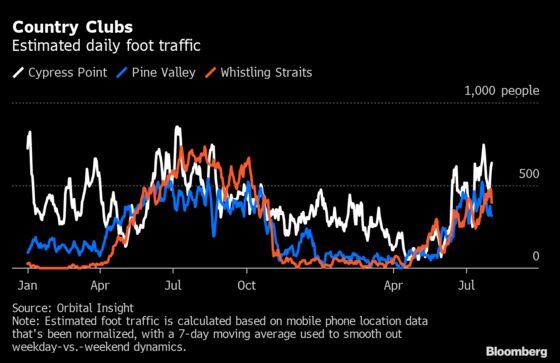

At the other end of America’s economic strata are those who find themselves without enough money to eat. In March, nearly 200 U.S. food banks suddenly became lifelines to the thousands who never needed such assistance.

According to Lee Lauren Truesdale, chief development officer at The Foodbank Inc. near Dayton, Ohio, February was fairly normal with almost 2,350 people served. In March, that number doubled and the National Guard arrived late in the month to help with distribution. In April, nearly 8,700 people received its emergency food assistance with the help of two off-site distributions in a university parking lot nearby.

An even bigger influx occurred at the Weld Food Bank in Greeley, Colorado, where strong demand appeared to be sustained through July, according to the mobile-phone data.

At the Food Bank of Siouxland in Iowa, Orbital’s data didn’t capture the jump in demand, but only because it doesn’t have a distribution pantry at its address where phone activity was measured and staff started working from home, according to Valerie Petersen, the depot's development director. Siouxland gave away more than 300,000 pounds of food per month from March through June, breaking earlier records, and 46% more in July than a year earlier.

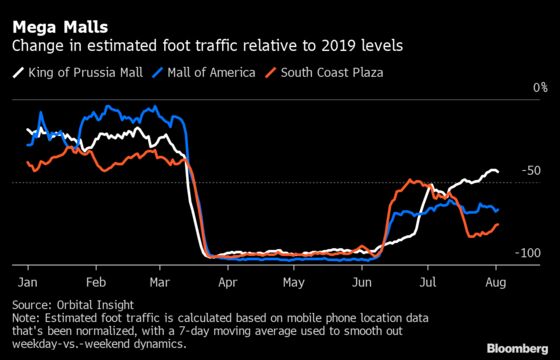

Mauled at the Malls

As many as 25,000 stores are expected to close in the U.S. in this year, mostly in shopping malls, according to Coresight Research. Bankruptcies are piling up, leaving landlords and their retail tenants to worry about the future.

At South Coast Plaza in Southern California, the Mall of America near Minneapolis and King of Prussia mall northwest of Philadelphia, activity is returning slowly but still looks down 44% to 76% from a year ago, Orbital’s phone data show. That matches up with what mall tenants are seeing.

“In the larger indoor shopping malls, we are seeing traffic gradually increase,” said Craig Migawa, the owner of Pepper Palace Inc., a chain of hot-sauce and spice stores with more than 80 locations, including one in the Mall of America in Bloomington, Minnesota, and in King of Prussia, Pennsylvania.

He said shopping centers are doing a good job of offering hand-sanitizing stations, masks and social-distancing signage. His stores are now providing “sampling gloves” for taste-testing customers and requiring a new spoon for each sample. A new “Sauce Finder” will help customers browse on iPads throughout the sales floor.

Migawa said he suspects traffic will return to pre-pandemic levels for retailers that offer an experience so it’s more of a “fun thing to do and less of a gathering of essentials that can be done online.”

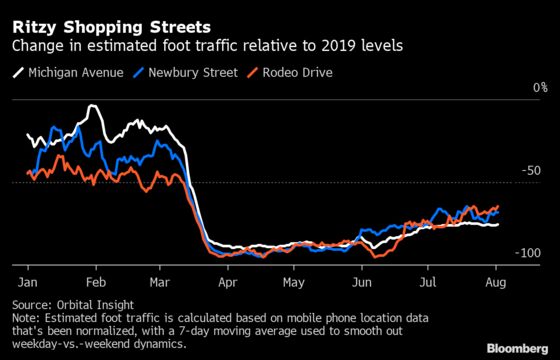

‘Kind of Creepy’

In upscale urban shopping districts from Rodeo Drive in Beverly Hills to Chicago’s Michigan Avenue, the summer flocks of tourists aren’t materializing like usual and activity looks to be 25% to 36% of last year’s level.

Along Boston’s Newbury Street, a corridor of cafes, spas, museums and boutiques, mobile-phone activity looks to be about 32% of levels a year ago. Stores that are able to reopen are making adjustments like those at Winston Flowers, a 75-year-old family business.

Co-owner David Winston said the city’s Back Bay area has been eerily quiet since mid-March. The pandemic struck florists during one of their busiest stretches of the year — Easter, Mother’s Day, Secretary’s Day and graduations. Winston reopened the Newbury shop on Thursday, hoping for a return of residents nearby who fled the city and workers trickling back to the office.

Winston said he’s reorienting the Newbury location to focus more on household plants, pots and accessories and less on labor-intensive floral arrangements. Going forward, the New England flower shop will scale back from seven to four locations including the one on Newbury, where only Brooks Brothers has been in business longer, he said.

“I know the pulse of the street pretty well and it’s been kind of creepy the past four months,” Winston said. “It’s really different. There’s a lot of vacancies, the traffic is lighter, I feel bad for the restaurants — I don’t know how they do it. It’s a really interesting and kind of a sad time.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.