(Bloomberg) -- The buyout industry is making a renewed push to change some of the world's least-friendly takeover rules in India.

Encouraged by a surge in private equity deals that has mostly focused on non-listed Indian companies, bankers and other buyout specialists are lobbying to overhaul a process that leaves little room for buyers to set a price based on their valuation of the company.

They hope the Securities and Exchange Board of India, under new chief executive Madhabi Puri Buch, will amend the rules after the regulator made changes to a framework in 2021 that made it easier to delist a company if there was a change in control.

“I would really like to see some reform in regulations, particularly for someone who wants to take a company in the private domain and do something more with it,” Raj Balakrishnan, co-head of India investment banking at Bank of America Corp., said at an industry conference in September.

Price Uncertainty

As it stands now, under take-private deals in India, a buyer sets a floor price based on their valuations of the company. The final price, however, comes about after taking bids from all shareholders, a so-called reverse book-building process that can significantly increase the offer price for the company.

This differs from a fixed price mechanism in the US and UK, where the buyer sets the offer price.

Such a process in India was established about 20 years ago to protect smaller shareholders who could feel squeezed out, and it has its admirers. “It is unique to India and the cleanest and fairest price discovery mechanism,' said Hetal Dalal, president and chief operating officer at Institutional Investor Advisory Services, a proxy advisory firm. “Everybody gets a choice.”

Critics say the price uncertainty arising from this process in India has prevented firms from using a well-tuned private-equity play book to improve operations and governance, which could increase the value of those firms. Under this reverse book building, existing shareholders could band together to bid unrealistic levels, pushing up the final price for the shares, they said.

Market participants have written letters to authorities and stressed this during conversations with government officials about why the current process is tortuous and how further easing the rules would help expand capital flows into the country, according to nearly a dozen fund managers, bankers and lawyers familiar with the process.

India's “process does not provide clarity or certainty with respect to the pricing and what happens next,” said Harsha Raghavan, managing partner of Convergent Finance, an investment firm which takes stakes in both private and publicly-traded companies.

Delisting Changes

The new rules set last year had timelines for the delisting process and calculation of book value in case the offerer did not accept the discovered price and wanted to make a counter offer. The regulator, however, did not accept the recommendation to modify the price discovery process.

“There has been a lack of sophistication on behalf of the regulators and they are playing catch up after years of lack of rigor on who they approved to be listed,” said Jahnavi Kumari Mewar, chief executive officer and senior portfolio manager at JPM Capital.

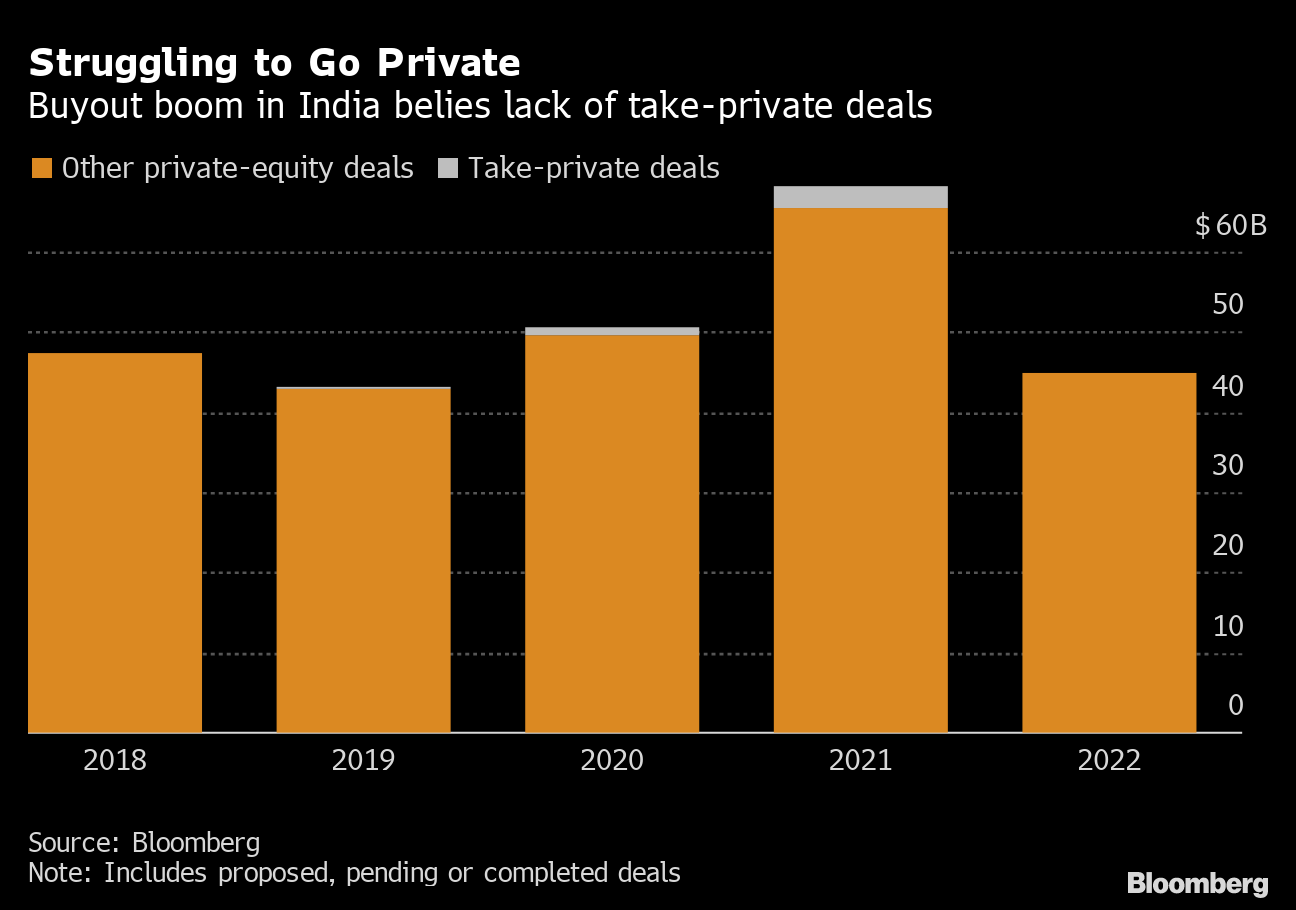

Over the years, there's been a paucity of privatizations in India amid a boom in deals.

Since 2003, only about 277 companies filed to delist from Indian stock exchanges, according to data from PRIME Database Group, which covers fundraising by Indian companies and the government. Private-equity deals accounted for just a handful, according to the data. In contrast, private-equity firms have worked on almost 130 take-private transactions globally, worth more than $290 billion so far this year, data compiled by Bloomberg show.

In India, bigwigs like Blackstone Inc, Carlyle Group Inc. and KKR & Co Inc. have individually deployed more than $1 billion to take a majority control in companies in the last three years, according to a June report from consulting firm Bain & Company.

“The expansion in buyouts coupled with larger valuations is leading to a higher emphasis on value creation through operational turnarounds, for which funds are setting up internal operations teams,” the report said.

Deals

Privatization has been a familiar tool for buyout firms toward this aim. This can be hard to pull off in India, even for local tycoons. Billionaire Anil Agarwal's Vedanta Ltd. couldn't get privatized after opposition from minority shareholders two years ago, while Gautam Adani's power company recently pulled its plan to delist.

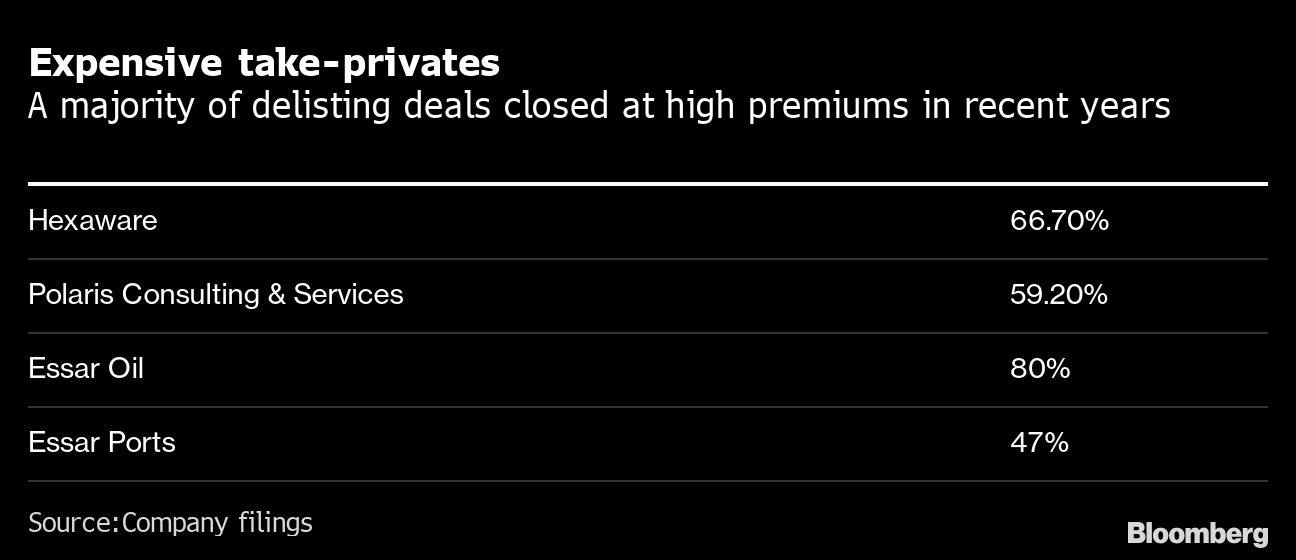

These processes can be expensive there too. For deals worth over $100 million that went through over the last seven years, four in five buyers paid premiums in the range of 45% to 67%, almost double the premiums globally, according to data analyzed by Bloomberg.

In 2020, Baring Private Equity Asia took Hexaware Technologies Ltd. private in one of the largest delistings in the country. The firm's bid to delist Hexaware was eventually done at the “discovered price” of 475 rupees per share, a premium of 66.7% above the floor price of 285 rupees per share.

Then there is Boston-based Advent International Corp., which is in the process of delisting DFM Foods Ltd. The private-equity firm set a floor price at 220.64 rupees when it announced its take-private plan in August. Shares of DFM, which Advent bought a majority stake in 2019, have been trading above 370 rupees.

Advent and Baring declined to comment for the story. The regulator SEBI did not respond to emails asking if they plan to make any changes to their delisting policy.

“The Indian markets have to be less protectionist to benefit someone who can create more value for their shareholders,” Bank of America's Balakrishnan said at the conference.

--With assistance from and .

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.

Essential Business Intelligence, Continuous LIVE TV, Sharp Market Insights, Practical Personal Finance Advice and Latest Stories — On NDTV Profit.