US job growth was far less robust in the year through March than previously reported, adding to mounting pressure on the Federal Reserve to lower interest rates.

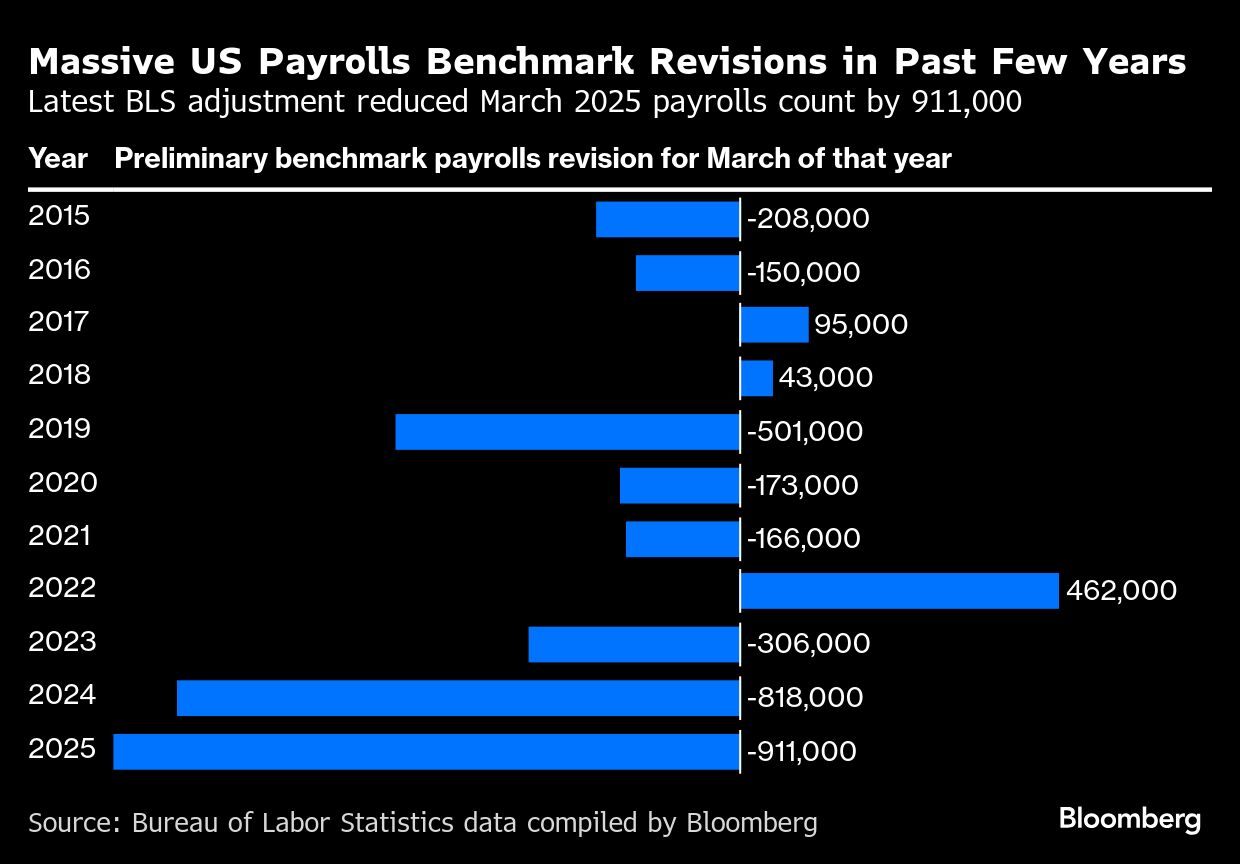

The number of workers on payrolls will likely be revised down by a record 911,000, or 0.6%, according to the government's preliminary benchmark revision out Tuesday. The final figures are due early next year.

Before the report, the government's payrolls data indicated employers added nearly 1.8 million total jobs in the year through March on a non-seasonally adjusted basis, or an average of 149,000 per month. The revision showed average monthly job growth was roughly half that.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics adjustment indicates the labor market slowdown in recent months followed an extended period of more moderate job growth that may lay the groundwork for a series of interest-rate cuts beginning next week. Fed Chair Jerome Powell recently acknowledged risks to the job market have increased, and two of his colleagues preferred to lower borrowing costs in July.

Traders widely expect central bankers to cut rates at the conclusion of their two-day meeting Sept. 17. Treasury yields rose while the S&P 500 reversed earlier gains.

The labor market “was materially weaker than the BLS initially estimated in the year to March 2025, giving the Fed another reason to lower rates next week,” Sal Guatieri, senior economist at BMO Capital Markets, said in a note.

Payrolls were marked down in nearly every industry and most states. Combined payrolls at wholesale and retail establishments led the downward revision, followed by leisure and hospitality. Professional and business services as well as manufacturing were also notably marked down.

While benchmark revisions are carried out every year, they've garnered added attention this year with investors and Fed watchers looking for any signs that the labor market may be slowing faster than previously thought.

Political Ire

Sizable adjustments to monthly job data sparked outrage at the White House and led to President Donald Trump's dismissal of the head of the BLS in August. Last year, he took aim at former President Joe Biden, calling into question the integrity of his administration and its economic record after a similarly large downward revision in the 2024 preliminary benchmark revision.

The final 2024 revision was ultimately not as severe as the preliminary suggested, though it was still the largest since 2009.d

“Today, the BLS released the largest downward revision on record proving that President Trump was right: Biden's economy was a disaster and the BLS is broken,” White House Press Secretary Karoline Leavitt said in a statement. “This is exactly why we need new leadership to restore trust and confidence in the BLS's data.”

While Trump has been critical of revisions, both the monthly and benchmark adjustments are part of a routine process of updating estimates as more data become available. Adjustments have been bigger than usual in recent years, which some economists attribute to unique post-pandemic dynamics.

“Today's massive downward revision gives the American people even more reason to doubt the integrity of data being published by BLS,” Labor Secretary Lori Chavez-DeRemer said in a statement. The Labor Department oversees the BLS.

“Considering these reports are the foundation of economic forecasts and major policy decisions, there is no room for such a significant and consistent amount of error. It's imperative for the data to remain accurate, impartial, and never altered for political gain,” she added.

Several economists said the initial payrolls data may have been impacted by a number of factors, including adjustments for the creation and closure of businesses and how unauthorized immigrant workers are counted.

The BLS compiles each monthly employment report from two surveys. The benchmark revisions pertain to payrolls, which are gathered through a survey of businesses. They don't affect the unemployment rate, which is derived from a survey of households.

Once a year, the BLS benchmarks the March payrolls level to a more accurate but less timely data source called the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages that's based on state unemployment insurance tax records and covers nearly all US jobs.

The preliminary figure applies to the total level of payrolls in March 2025. The final numbers, which are released with the employment report due next February, will break out the revisions by each month.

For most of the recent years, initial monthly payroll data have been stronger than the QCEW figures. Some economists attribute that in part to the so-called birth-death model — an adjustment the BLS makes to the data to account for the net number of businesses opening and closing, but that might be off in the post-pandemic world.

Others have argued there's another reason behind that discrepancy: immigration. Because the QCEW report is based on unemployment insurance records — which undocumented immigrants can't apply to — the data are likely to have stripped out up thousands of unauthorized workers that were included in the initial payroll estimates.

Essential Business Intelligence, Continuous LIVE TV, Sharp Market Insights, Practical Personal Finance Advice and Latest Stories — On NDTV Profit.