(Bloomberg) -- The outlook for China's economy is somber. Exports have cratered, manufacturing is slowing and a property slump is weighing on consumer spending. Youth unemployment has skyrocketed, and these days, even high-earning professionals are feeling the pinch.

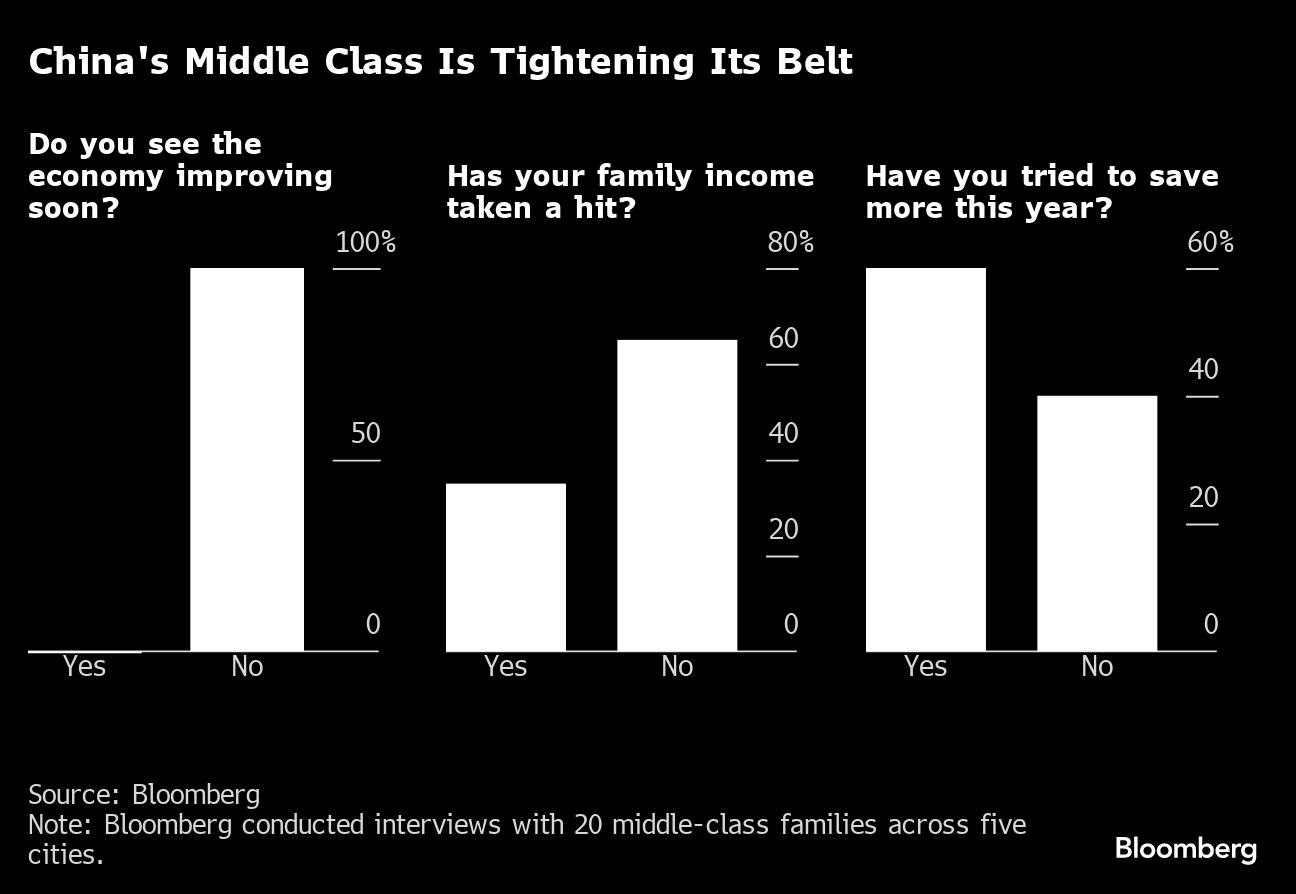

Interviews with 20 college-educated people across five top-tier Chinese cities show how the nation's middle to upper class — a consumer powerhouse targeted by global brands — is pulling back.

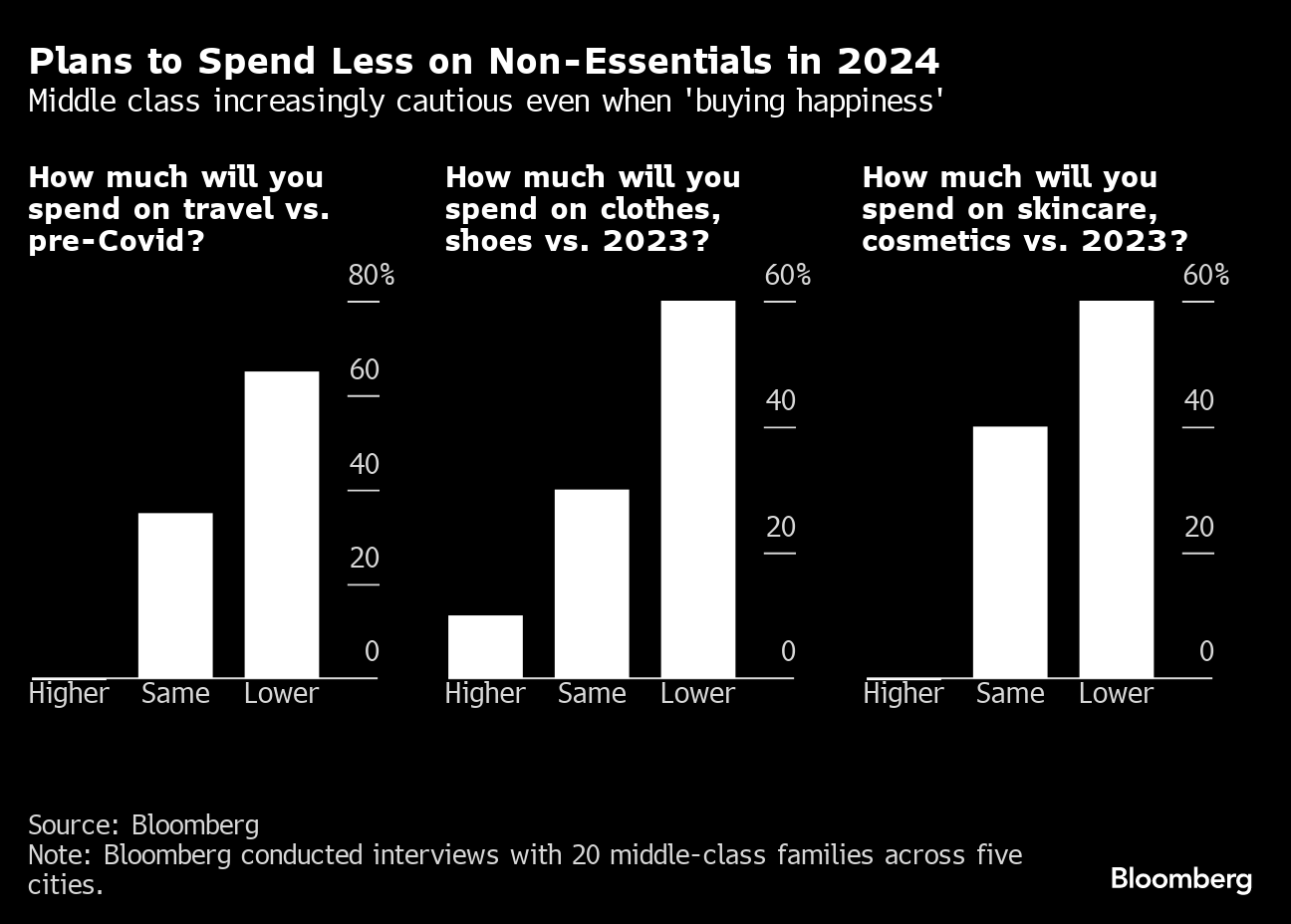

Uniformly, the group said they were limiting spending on non-essentials, delaying major purchases like homes and cars and putting more money into savings. Unease about job security came through strongly. The thought of sending children overseas for further education has taken a back seat.

It's a minute sample but if extrapolated, points to a rocky few years ahead for the world's second-largest economy. These executives, from Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, Shenzhen and Hangzhou, are arguably at the peak of their spending prowess. If they're nervous, swathes of China's other 1.4 billion consumers are probably just as apprehensive. Millions of small, spending-pullback decisions will amount to big shocks for international companies from Starbucks Corp. to Apple Inc. and Estee Lauder Cos.

Luxury and Discretionary Spending

In Shanghai's Zhangjiang neighborhood, Zhang Mei, a 40-year-old software engineer, is one of millions of Chinese working in technology, an industry rattled by Beijing's sweeping graft crackdowns. The scrutiny has fueled job cuts and pay reductions among workers who've grown accustomed to a certain lifestyle.

Even though she's making around 1.2 million yuan ($170,000) a year and her husband also has a good job, Zhang has reduced impromptu spending. A few years back, headhunters regularly called with offers that would have doubled her salary. Now, the mom of two has stopped buying expensive dresses or taking spur of the moment weekend trips to places like Japan.

“In ten years, I'll be 50, and very likely on the layoff list,” Zhang said.

Zhang's more modest outlays chime with the broader lackluster consumer outlook. McKinsey & Co., in a recent China consumption report, declared the era of double-digit retail growth “over.” Daniel Zipser, who leads the firm's consumer and retail efforts in Asia, said sentiment was “around an all-time low, with meaningful concerns on the economic outlook.”

Also in Shanghai, Amanda Lin, a 34-year-old working in financial product sales for a state-run brokerage, has made millions of yuan in annual bonuses in years past. She's now girding for a significant bonus cut in 2023 and says she's taken a “psychological hit” as her investment portfolio declines.

Discretionary spending is also muted among people who don't have children. Tracy Mao, a 32-year-old human resources employee at a top Chinese tech company, and her husband spent big this year following their wedding: hundreds of thousands of yuan on home furnishings, a honeymoon in Japan and a $1,400 Canon camera.

Now, they're curbing their spending as layoffs grow. Gripped by a deep sense of job insecurity, both want to save more for the future. The tech-savvy couple even delayed purchasing the new iPhone 15s until they were able to find ones at a discount.

Savings

Most people are also concerned about finding the safest place to invest — a potential bright point for China's financial institutions.

Some once-prolific shoppers are using that money to invest instead. Data released by the People's Bank of China last month showed that Chinese households added 13.8 trillion yuan ($1.89 trillion) in savings in the first 10 months of the year, up 8.5% from a year earlier.

Insurance sales agent Manna Wang, who has a masters degree and lives in Shenzhen, said she's had a good 2023 selling products to customers seeking US dollar-denominated protection. Next year, the 36-year-old expects business will surpass pre-Covid levels as wealthy Chinese look for ways to derisk their investments.

Once upon a time, Wang, who owns three properties, would have spent that extra income. But in the current climate, she's putting any extra into savings. She's also considering selling her two investment properties so she can put the cash into annuities.

Read more: China's Real Estate Meltdown Is Battering Middle Class Wealth

“I can't stand to think about my living quality getting worse when I retire,” Wang said.

Jason Wang, a 39-year-old living in Beijing, is recently unemployed and now lamenting his lack of savings. Since losing his $140,000-a-year job at a health care startup in August, his family income has more than halved and his wife is expecting their first child in January.

“I'm feeling anxious,” he said. “I just bought a home and upgraded to a BMW SUV. I'm going to give myself another three months to find a job that pays as well as my previous one. If that doesn't work, I'll look at getting into an industry with lower pay but better prospects over the long term.”

Food

Even as much of the developed world cuts back on grocery spending amid soaring inflation, many interviewees said they were maintaining their food budgets, and in some cases raising them. Several said the pandemic had inspired a greater interest in health and wellness with higher-quality food playing a big role.

Hangzhou resident Dong Sihao, who works in product research, has begun stocking up at Walmart Inc. warehouse chain Sam's Club — a discount destination in the US but an increasingly popular status symbol store in China. He goes at least twice a month and favors quality fruits with perceived wellness benefits.

Covid “made me more willing to spend on a healthier lifestyle,” Dong, 31, said. “Eating better is a part of it and it's also a way to enjoy life.”

It's the same for Mai Mai, 34, who owns a meditation studio. Despite being worse off financially as clients were slow to return after China's strict Covid measures, she and her husband raised their food budget, allocating more to higher-quality meat and fresh produce. In her fridge are more groceries from Hema Xiansheng, the grocery brand under Alibaba Group Holding Ltd.'s supermarket chain Freshippo, and fewer purchases from the local wet market.

Foreign Education

An overseas college or graduate degree has long been a status symbol among well-off Chinese — one of the largest groups of international students on campuses from the US to Australia — and seen as a ticket to a steady career back home.

While some of the professionals are still planning to send their kids abroad, surging youth unemployment is changing perceptions about how much a foreign diploma is worth.

Read more: China Job Crisis Pushes Young City Workers to Rural Areas

Even as Beijing encouraged Chinese students to return overseas after Covid, the number studying at US colleges and universities was flat at about 290,000 in the 2022-23 school year. Political tensions with the US are also changing the calculus.

Tina Li, a 37-year-old freelance photographer in Shanghai who's married to an executive at a automaker, doesn't plan to send her son, currently at a public school, overseas for university. “Those who study abroad might not find it easy to get a good job when they get back home,” she reasons.

Travel and Experiences

Our interviewees were largely still willing to shell out on local travel and other intangible experiences, with some calling it a way to buy happiness in an otherwise stressful time.

At the lower end of the financial spectrum is Anna Liu, a 33-year-old fitness instructor and single mother in Shenzhen. She normally earns around $84,000 a year but found her income squeezed after clients dropped about 20% of their sessions this year because of their own financial stresses.

But she's a huge fan of Cantonese pop music and 2023 was the first year live concerts were back after Covid. She's spent around $7,000 on tickets and hotels to attend gigs in China over the past 12 months.

Outside of China, holiday hotspots are waiting for Chinese tourists to return. The World Travel & Tourism Council estimates Chinese outbound travel may take until the end of 2024 to get back to pre-Covid levels with flight capacity, high airfares and difficulties in getting visas and passports key bottlenecks.

Dong from Hangzhou said while he's dialed back pricey social outings, he and his wife budget for at least one domestic trip a month. While overseas airfares are too high at the moment, “we want to seize the moment and enjoy life more.”

--With assistance from Venus Feng, Lulu Shen and Qizi Sun.

More stories like this are available on bloomberg.com

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.

Essential Business Intelligence, Continuous LIVE TV, Sharp Market Insights, Practical Personal Finance Advice and Latest Stories — On NDTV Profit.