There are two types of countries in the world: those that worry about whether they will have a sufficient supply of Covid-19 vaccines to jab their population within the next few months, and those that know they don't. The first group are Vaccine Protectionists, while the second are Vaccine Free Traders.

Economically, developed countries populate the first category, while developing and least developed ones populate the second. That's ironic because traditional trade positions are reversed. Richer countries incline to free trade. Poorer ones worry about protecting infant industries and small and medium-sized enterprises.

Historically, the two categories of countries are redolent of a mid-20th century ‘First World – Third World' confrontation. Haves versus Have Nots, in that Vaccine Protectionists have the vaccine, and Vaccine Free Traders don't. A Bloomberg study found that ‘more than 20% of the population in countries including Israel, the U.K., Bahrain, and the U.S have received at least one shot, while few African nations received a single shipment of shots before March'.

Politically, the first group stands accused of privileging its nationals. That explains the common rubric of ‘vaccine nationalism'. However, that's an over-used, under-defined term. A more lawyer-like understanding of cross-border supply-demand imbalances in the Pfizer/BioNTech, Moderna, Oxford/AstraZeneca, and other approved vaccines uses different terminology and reveals the legal, geopolitical, and moral arguments at play.

‘Vaccine Protectionism', Not ‘Vaccine Nationalism'

True, holding back vaccines from another country is detrimental to that other country, meeting one part of the lexicographic definition of nationalism. Except for Trumpian America Firsters (a big exception, admittedly), there is no specific political ideology causing one group of countries to be hesitant about shipping vaccines to a second group of countries. Rather, the first group is driven by vaccine insecurity, not having enough vaccine to jab their people. That's just like food insecurity, not having enough grains to feed their people.

And, of course, there is a lot of vaccine insecurity. In just the last week:

- On March 18, United Kingdom Health Secretary Matt Hancock told Parliament that doses of the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine made by the Serum Institute of India have been stalled. Serum's CEO Adar Poonawala told Bloomberg in an interview the previous day that the company had been directed to prioritise India and other countries with a high burden of the disease.

- On March 17, The European Commission President threatened to halt Covid-19 vaccine exports to the U.K. unless “Europe gets its fair share”.

- On March 12, the Biden Administration said it is holding on to its stockpile of AstraZeneca vaccines, even though the shot isn't authorised for U.S. use, rebuffing pressure from Europe and the company to consider sharing doses of the shot.

Vaccine insecurity translates into a specific trade policy, just like food insecurity: protectionism.

Central governments concerned about running out of a critical product turn to legislation, like the 1950 U.S. Defense Production Act, to intervene in private contractual arrangements (between vaccine producers and consumers), commandeer supplies, and direct them to their citizens based on domestic priority rankings (essential workers and the elderly first). Those interventions impinge on free trade to ensure pharmaceutical companies don't sell to the highest bidder regardless of location.

No International Trade Law Obligation To Export

None of the 164 World Trade Organization Members has a duty to export anything, nor a right to import anything. The rules of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade and WTO set the conditions for cross-border trade in goods and services, but they don't mandate that trade occur.

Indeed, the basic rule in GATT against the imposition of quantitative restrictions on exports or imports is subject to a major exception:

Export prohibitions or restrictions temporarily applied to prevent or relieve critical shortages of foodstuffs or other products essential to the exporting contracting party.GATT Article XI:1, Paragraph 1(a)

Without a doubt, vaccines are an “other product essential,” and thus a proper subject for a “temporary” export ban to “prevent or relieve a critical shortage” of them.

The key terms, such as “essential,” are self-judging, at least when it matters most. That is, a Vaccine Protectionist facing a crisis will impose a trade-restrictive measure on vaccine exports. It'll be for a Vaccine Free Trader to bring suit alleging one or more of the terms were unfulfilled. If the Protectionist had to await approval of the WTO Membership, or a victory in a WTO Panel case (remember, the Appellate Body is dead, so getting its opinion isn't even an option), then the response to the crisis might come too late to help its public.

Plus, a government facing a public health crisis that awaits a multilateral blessing for restricting trade in vaccines is a government inviting its citizens to toss it from power.

Compulsory Licensing: Leverage For Free Traders

In 2005, Articles 31(f) and (h) of the WTO Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights were amended. The amendments were waivers from adherence to normal TRIPS patent protection obligations.

A country may issue a compulsory license, thereby overriding patent rights, and import generic drugs to treat public health matters. That's true for ones known when the amendment was made, such as HIV/AIDS, malaria, and tuberculosis, and must be so for ones not known, such as the coronavirus. Otherwise, compulsory licensing would be ridiculously circumscribed to diseases known at the time. The waivers remove the constraint that generics made under a compulsory license should be primarily for the domestic market of the country granting the license and thus permit the exportation of generics to a country lacking manufacturing capacity.

Always there as a partner.

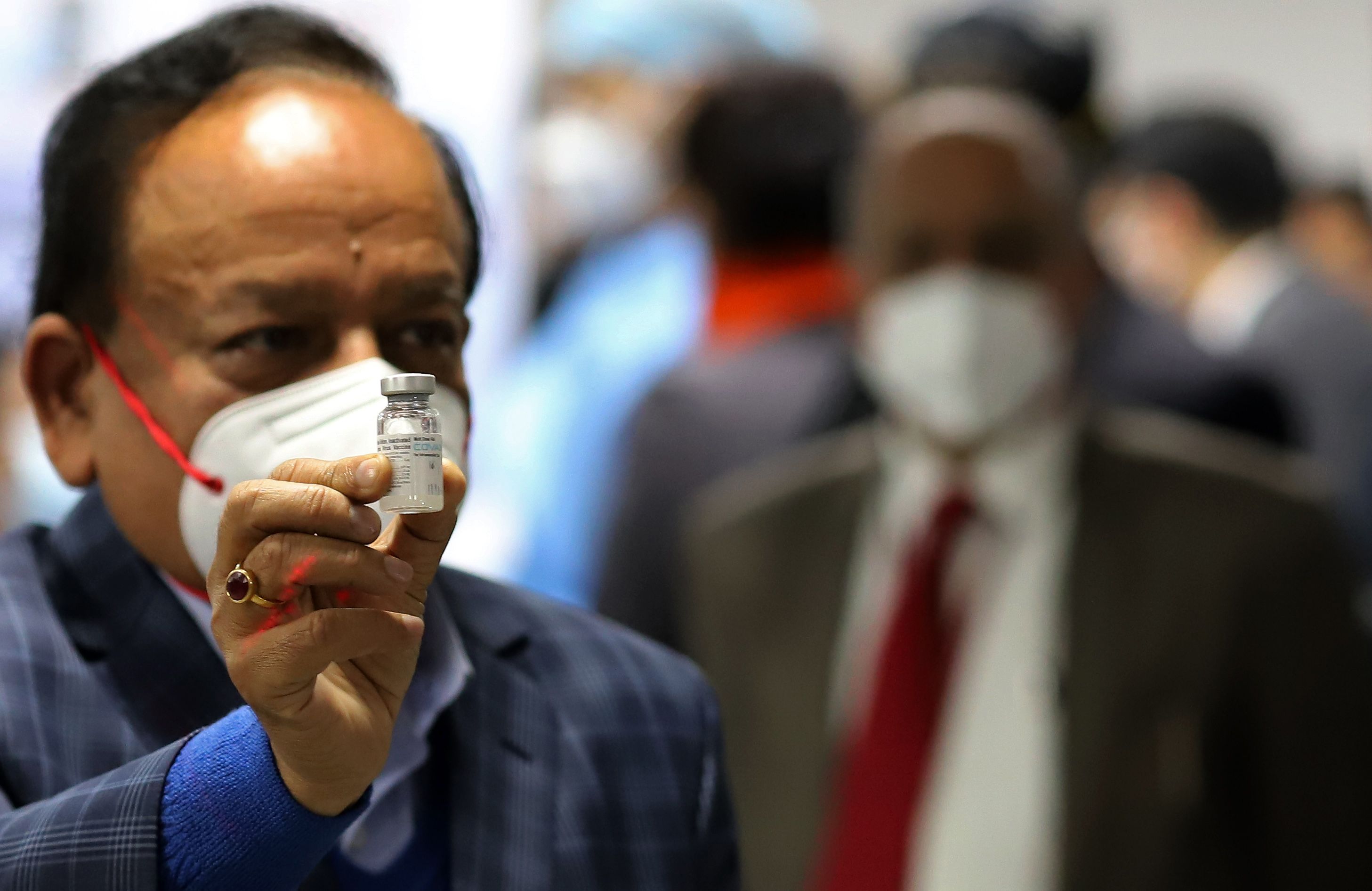

Made in India vaccines arrive in Eswatini. #VaccineMaitri pic.twitter.com/Y2rNMLECO7Vaccine Protectionists beware.

If there isn't really a bona fide ‘shortage' of vaccines (as seems to be increasingly true in the U.S.), then a Vaccine Free Trader may invoke TRIPS Article 31. Normally, Vaccine Protectionists could insist on their right to negotiate “reasonable commercial terms” with the Free Trader to obtain the vaccines without breaking the patent. But, in cases of “public non-commercial use,” where the Free Trader suffers a “national emergency or other circumstance of extreme urgency,” there's no need to bargain.

To be sure, Vaccine Free Traders don't have unbridled freedom to invoke a TRIPS waiver:

- They must restrict the scope and duration of the compulsory license to the authorised purpose. Their use of the vaccine must be “predominantly for the supply of the domestic market” – not diverted to a third country for profit.

- They're liable for payment of compensation to the country exporting the generic version of the vaccine they compulsorily license and import, but not to the patent holder, as that would be a double burden.

- They must pay heed to notice requirements owed to the WTO but needn't get WTO approval.

On balance, the leverage to invoke compulsorily licensing is considerable. India knows. It granted its first such license in March 2012, concerning Nexavar, which Bayer patented to fight kidney and lung cancer, but which Natco Pharma produced generically under the license.

Geopolitical Logic

That logic is showing up China in an era of great power competition. The recent Quad announcement to provide one billion vaccination donations by the end of 2022 for the 10-member Association of Southeast Asian Nations, and even beyond ASEAN, is a brilliant illustration. The U.S. and Japan agreed to fund the vaccines, Australia agreed to distribute them, and India agreed to manufacture them.

The Chinese Communist Party simply can't pull off this feat

The Quad plan could help both synthesise and transcend the interests of Vaccine Protectionists and Free Traders in favour of the equitable distribution of vaccines regardless of boundaries.Imagine what Cambodians, Laotians, Thais, and Vietnamese will think when they see ‘Made in India' on vaccine containers as they line up for their jobs without incurring any debt. Perhaps the Chinese Communist Party's Belt and Road Initiative won't look quite as promising as collaborative action by four Indo-Pacific democracies.

Moral Logic

That logic is the promotion of human dignity in pursuit of the common good. Regardless of nationality, each person is unique, unrepeatable, and priceless. To promote the interest of each person, multiplied 8 billion times, is to promote the common good of humanity. Ironically, that – not the merciless pursuit of short-term self-interested protectionism – also resonates in the free trade theory articulated by Adam Smith and David Ricardo.

That logic is why the Dalai Lama wrote in November 2020 that the “current global health crisis … reminds us that what affects the human family has to be addressed by all of us” through “international cooperation … remember[ing] that we are one.” It's why Pope Francis said in his Christmas 2020 blessing “they [vaccines] need to be available to all.” And, if it's followed, the distinction between Vaccine Protectionists and Vaccine Free Traders won't matter anymore.

Raj Bhala is the inaugural Brenneisen Distinguished Professor, The University of Kansas, School of Law, Senior Advisor to Dentons U.S. LLP, and Member of the U.S. Department of State Speaker Program. The views expressed here are his and do not necessarily represent the views of the State of Kansas or University, Dentons or any of its clients, or the U.S. government, and do not constitute legal advice.

The views expressed here are those of the author, and do not necessarily represent the views of BloombergQuint or its editorial team.

Essential Business Intelligence, Continuous LIVE TV, Sharp Market Insights, Practical Personal Finance Advice and Latest Stories — On NDTV Profit.