Indra Nooyi's autobiography, My Life In Full, begins somewhat ploddingly—in an upper class, middle-income household of Madras of the 1950s and '60s. To an Indian reader, the picture she paints is not only very familiar but also somewhat boring in its plainness.

You'd imagine a woman that rose to become one of the most powerful business leaders in the world—the only Indian American, wait, the only woman, wait, the only woman of colour, to rise to the top of an iconic American giant like PepsiCo—would have had a more forceful debut in the world.

Instead, Nooyi writes about household chores and school and homework and about a well-to-do but frugal household dependent on her father's income from a bank job—a point brought home by a near-fatal accident—yet one that encouraged its daughters to study and make their own lives.

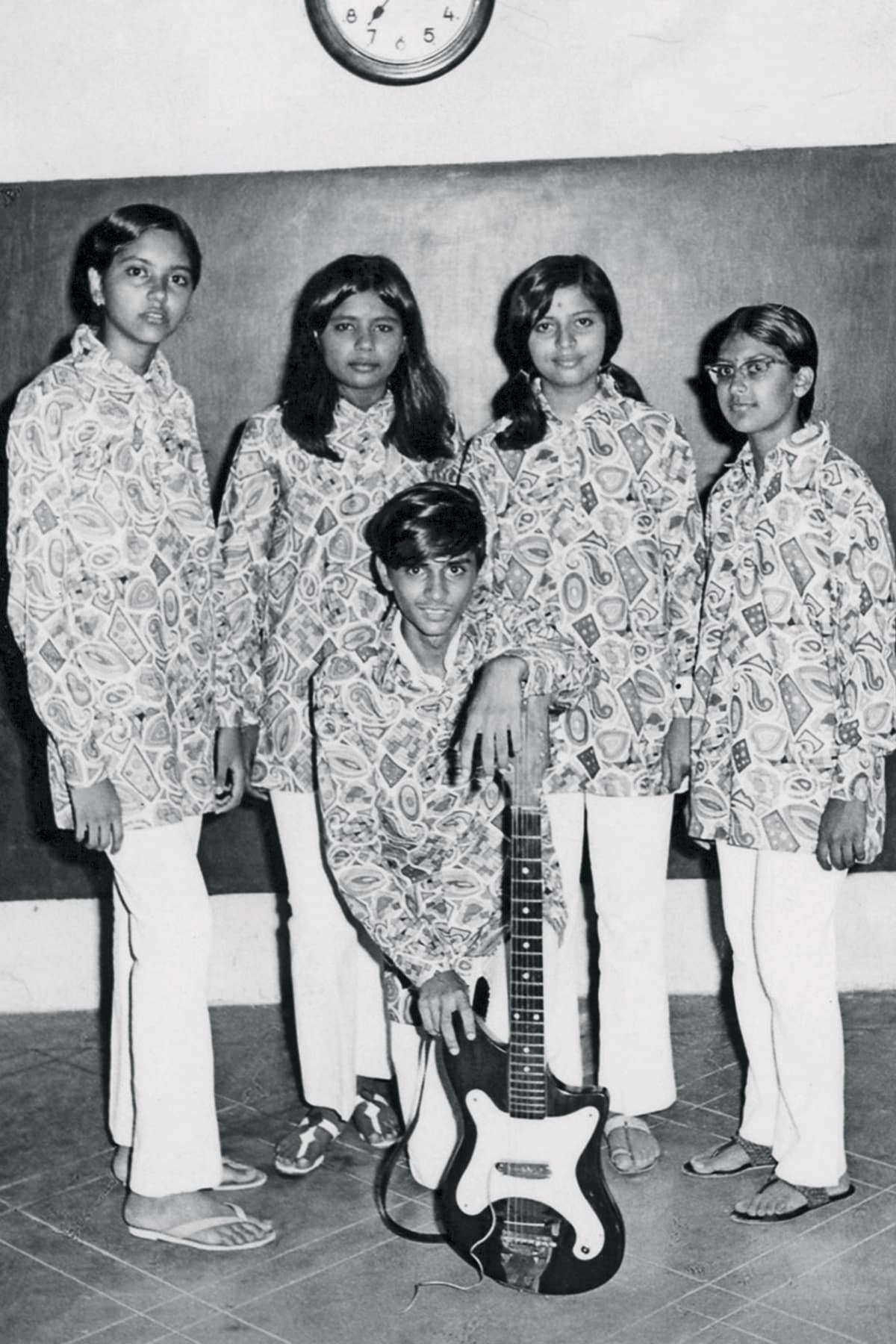

There's some spark no doubt in the young Nooyi—she forms a school band with friends, LogRhythms, and a cricket team in college. But no sign of burning ambition. At least not in the book. At least not yet.

LogRhythms - Featuring Indra Nooyi and classmates (Photo: Indra Nooyi family album)

Adulthood arrives at a similar pace—Catholic school to Madras Christian College to IIM-Calcutta to a summer internship with the Department of Atomic Energy in Bombay and then, after graduation, a job with a textile company in Mumbai.

So far so good and somewhat dull. And in that lies the beauty of this book.

Most such “leadership” books are written by male CEOs, of course, as if having this out-of-body experience while detailing the glory of their lives, almost in third person.

Nooyi keeps it real.

Indra Nooyi's family gathers to see her off as she heads to Yale. (Photo: Indra Nooyi family album)

Connettih-cut not Conneck-tih-cut, a friendly foreigner kindly corrects her on the flight to New York as she heads to Yale. An Iranian student introduces her to pizza (with chilli flakes for the spice craving). She falls in love with the Yankees and trips on polyester.

“My only worry was that I had no business suit. I headed back to Kresge's with fifty dollars, my entire savings at the time, and picked out a dark-blue polyester outfit—a two button jacket and matching slacks. I added a turquoise polyester blouse with light blue-blue and dark-blue vertical stripes.”

Too shy to use the changing room, Nooyi spends her precious money on an ill-fitting suit that draws gasps from her co-students gathered in the career office to meet prospective employers. She does alright on the interview, but, mortified by her attire, leaves dejected. In tears, she tells the director of career development what happened. Jane asks what Nooyi would have worn in India. A sari she says.

Those words ring through the book. They are the book.

Thereafter, at every turn in life, at least in the book, Nooyi gently attacks layer after layer of a working woman's existence.

She lays bare, again in the plainest of ways, the constant guilt of being a working mother:

“For many years, the guilt of not being a full-time mother to my kids in their early years gnawed at me. In some ways, I think of these days with great sadness.”

And yet, makes no apology for her ambition to work:

“I wonder why I am wired this way where my inner compass always tells me to keep pushing on with my job responsibilities, whatever the circumstances … I sometimes wish I were wired differently.”

Describes the career slog ungrudgingly:

“In fact, the day after Tara was born, Gerhard called me in the hospital to tell me about a project that would benefit from my input. I reminded him I'd just given birth and was recovering from surgery. 'But it's your body that had the baby,' he joked. 'Your brain is still working.'”

And makes peace (somewhat) with the evident discrimination, focusing instead on the satisfaction of making it to the top of the boys' club of corporate America:

Nooyi spends many pages on guilt—first words missed, uprooting the family for a new job, relying on her mother for childcare, the constant work-children time war.

“On a big sheet of construction paper, decorated with flowers and butterflies, she (Tara, her daughter) begs me to come home. 'I will love you again if you would please come home,' the note says. In her sweet, crooked printing, the word please is spelled out seven times.”

Nooyi makes no excuses for wanting it all. And, in its pursuit, expecting wide support. From household help to neighbours to parents and in-laws—she writes about how it takes a collective to allow women to work and have families. Lives and livelihoods.

“Gradually in Tara's first year, this big collective started to work for all of us. We got into a routine where I felt there was a group looking after the girls, and no individual was carrying the whole load.”

This is where the book becomes a blockbuster. Because this is where Nooyi becomes the protagonist of all our lives—the lives of all working women. Fraught constantly with dilemmas, guilt and the burden of making it work for everyone—spouse, parents, in-laws, children, friends, colleagues. Nooyi is clear. They've got to make it work for you. With you. It takes a collective. Women too.

Indra Nooyi: My Life In Full, published by Hachette India. (Cover photograph: Annie Leibovitz)

It's this quiet feminism that pervades the rest of the book. Or maybe, individualism. Because she plays the game yet doesn't conform. Big business deals, yes. Golf clubs, no. Hectic, unrelenting travel, yes. Management retreats, no. Activist investor battles, yes. Networking strategies, no.

Nooyi does it Nooyi style. Sans polyester.

“I decided to write to the parents of my senior executives. Over the next ten years, I wrote hundreds of notes, thanking mothers and fathers for the gift of their child to PepsiCo. I also wrote to the spouses of all my direct reports, thanking them for sharing their husband or wife with PepsiCo. I worked with my chief of staff to help personalise the letters for each recipient.”

For years, women leaders have tried to be male versions of themselves, to succeed.

“We have to demonstrate our gravitas in a world where authority and brilliance, to many people, still look like an older gentleman. And we have to absorb dozens of the simple, little slights that show women are not yet fully embraced."

U.S. President Donald Trump, center, speaks while Mary Barra, CEO of General Motors, from right, Stephen Schwarzman, co-founder and CEO of Blackstone Group LP, Indra Nooyi, chairman and CEO of PepsiCo Inc., and Ginni Rometty, president and CEO of IBM, listen. Feb. 3, 2017. (Photographer: Andrew Harrer/Bloomberg)

Nooyi speaks for generations of women, past and present, when she writes:

They do.

She converts one such judgment, on her attire—A BusinessWeek article described it as "business Indian"—into a mentoring moment. She narrates, both in the book and my interview with her, with a surprising degree of frankness, the story of how a young designer unexpectedly offers her a makeover. She accepts. No offence taken.

"At some point in my CEO years, I also learned about the power of looking the part."

In 1994, when Nooyi joined PepsiCo, not one of the 500 largest American companies had a woman CEO. When she was appointed chief executive in 2006, she was among 11. Now there are 41 women CEOs in the Fortune 500, yet only 13 in the Fortune Global 500.

Her 12-year tenure won her bouquets for foretelling the shift to healthier snacking and her Performance with Purpose campaign that recognised stakeholder capitalism earlier than peers. The brickbats were for an underperforming stock price and lack of aggressive acquisitions or value unlocking.

I should have written more about all that here—she does in the book. But any male leader can do the business bit.

It's taken a woman leader and her candid autobiography to refocus the world's attention from an alpha-male space race to ground realities.

“…I was among a vaunted group of global leaders regularly invited into rooms with the most influential leaders on the planet. And I came to notice that the painful stories about how people—especially women—struggle to blend their lives and livelihoods were entirely absent in those rooms. The titans of industry, politics and economics talked about advancing the world through finance, technology and flying to Mars. Family—the actual messy, delightful, difficult and treasured core of how most of us live—was fringe.”

Watch Indra Nooyi talk about work, family and the future of leadership here...

Essential Business Intelligence, Continuous LIVE TV, Sharp Market Insights, Practical Personal Finance Advice and Latest Stories — On NDTV Profit.