Behind the glossed perception of India being the fastest-growing economy and an oasis of growth amid a gloomy global order are some serious concerns.

The latest prints showcasing a downtrend in Q2 FY23 real GDP growth to 6.3% year-on-year and a sharp contraction in industrial production and exports suggest that the post-Covid bounties afforded by a stimulus-driven resurgence in advanced economies are fading rapidly.

A new structural trend of substantially lower GDP growth is emerging. Despite the statistical rebound, the post-pandemic trend is just 2.5% three-year CAGR over the pre-pandemic levels, nearly a fourth of the post-GFC 2008 revival at 9.7% and 5% during FY19-20

The sharp rise in external deficit to 5.9% of GDP in Q2 FY23 (exports-imports of goods and services) along with the core inflation averaging high at 6% since 2020 against a meager 2-3% growth in real expenditure depicts that India's potential growth, characterised by a balanced external account and 4-6% inflation, is now even lower than 2-3%.

This structural decline in real GDP has only compounded the lack of adequate employment and income generation. This has reduced household savings and overall savings rates to 14-year lows of an estimated 18% and 25.5% of GDP in FY23, respectively. This has been a drag on domestic investments.

Thus, this loop of declining investment and savings rates over the past decade has created a downward spiral of growth deceleration, rising unemployment, decelerating incomes, and rising fiscal burden as the loop has adversely impacted the lower-income section. At the current GDP growth rate, India would be absorbing not more than 20-25% of the annual 10 million job seekers joining the labor force.

Before the pandemic, we were already at a 45-year high unemployment rate of 6.1%. As per Centre for Monitoring of Indian Economy data, the unemployment rate currently stands at 8.0% (November 22); 3.5 crore out of 44 crore labor force are unemployed and actively looking for jobs. The unemployment rate for the youth age group of 25-29 years has risen to 14%.

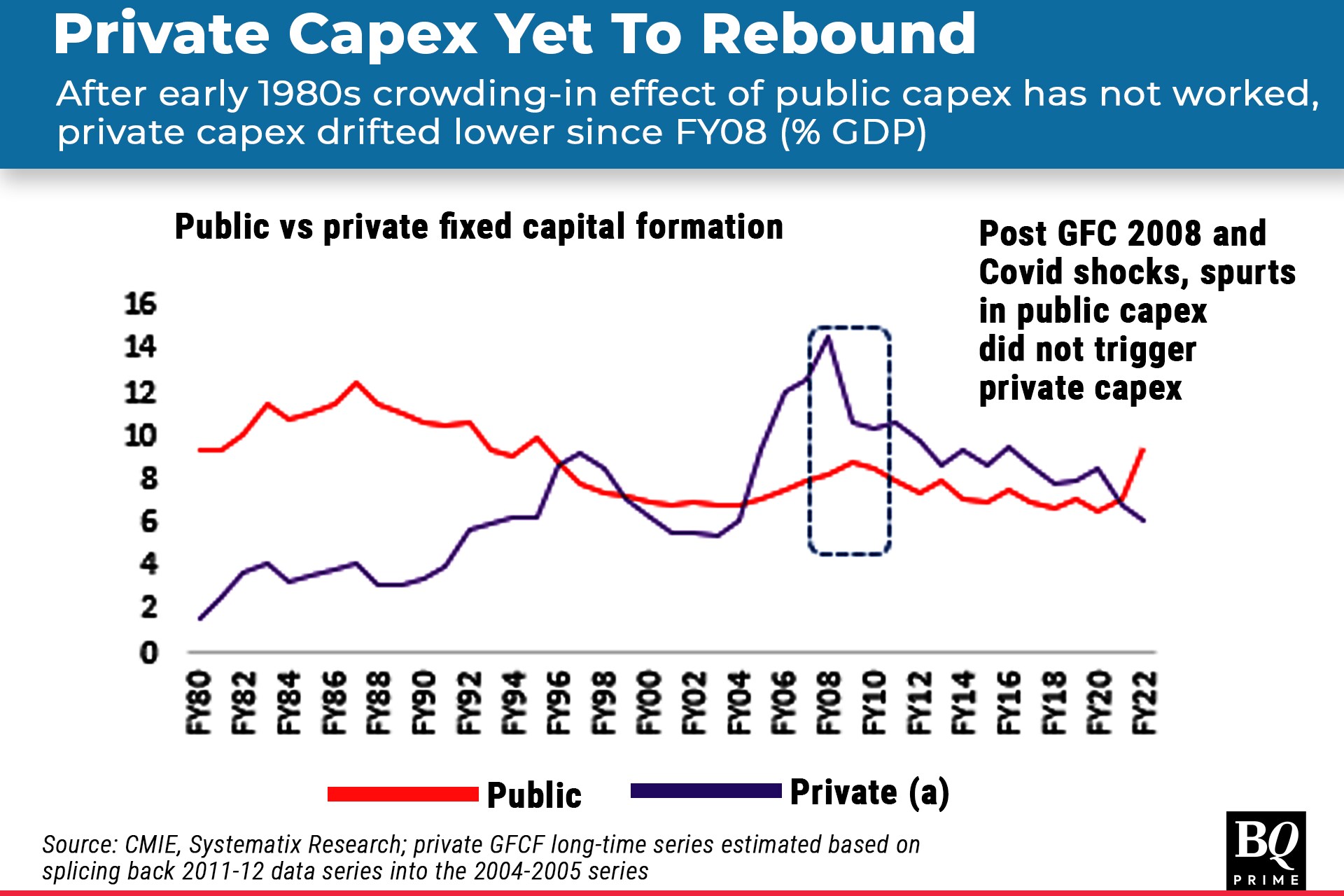

Over the past decade, India's policy response has been heavily biased towards the supply side, guided by the norm that sustained high government capex will crowd-in private investments.

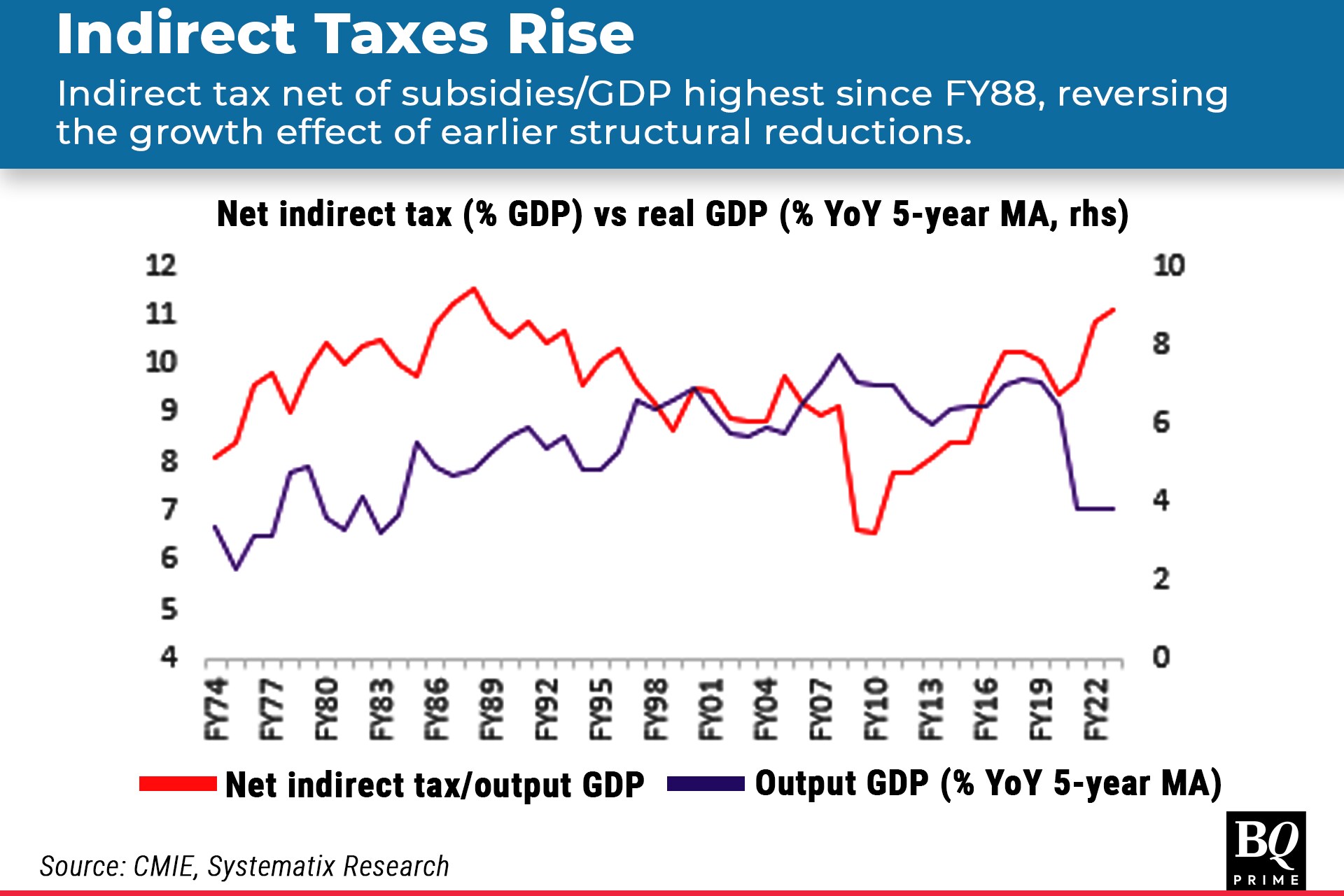

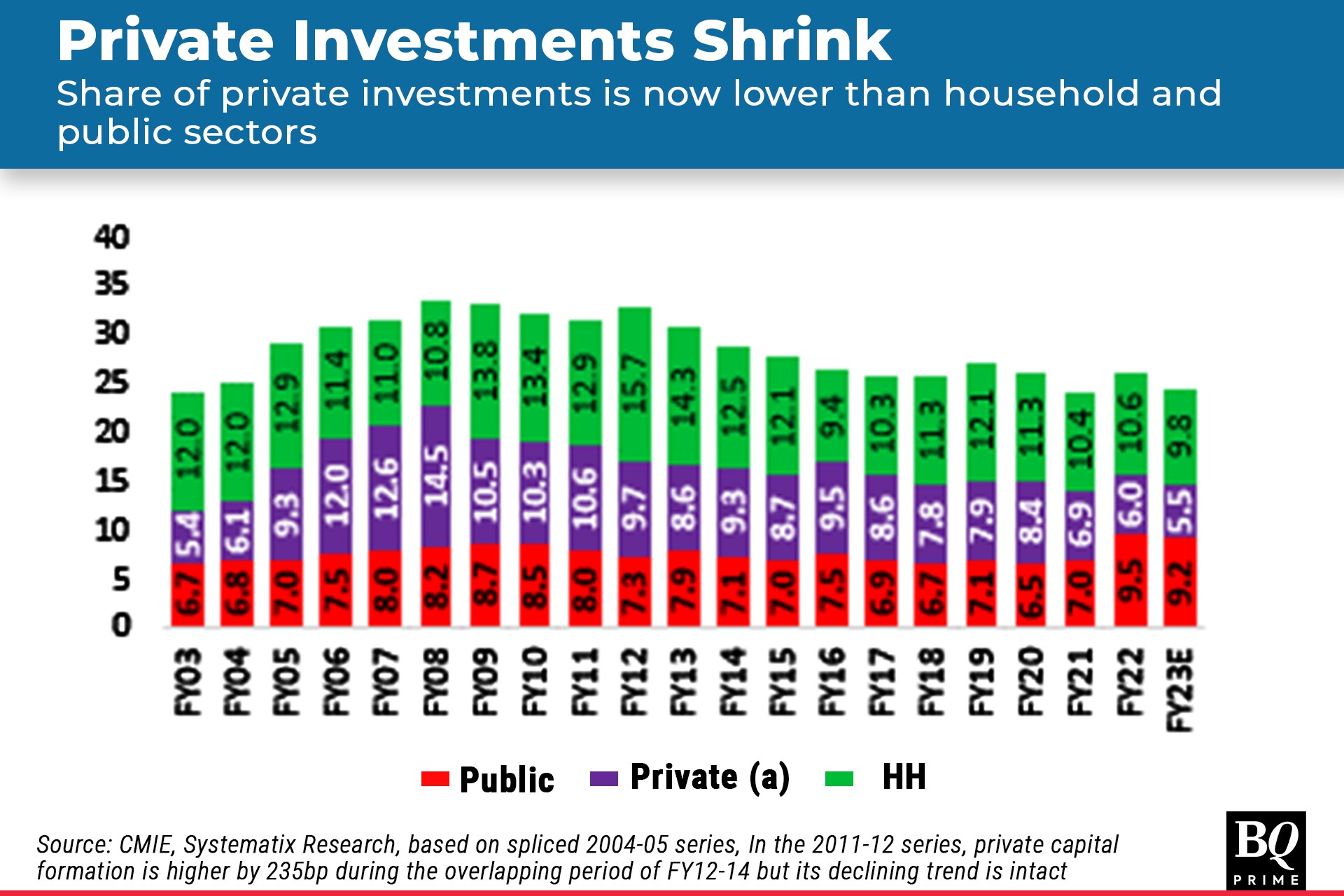

The share of public capital formation rose to 9.5% of GDP in FY22 from 6.5% in FY19, the highest since FY94. Besides these, lower interest rates and reductions in corporate tax rates were also deployed. Attempts to contain government deficits also saw a steep rise in indirect taxes. As a result, direct tax/GDP declined to 5.7% after a sustained rise to 7.3% from 2.3% during 1990-2008, while the incidence of net indirect taxes/GDP (indirect tax net of subsidies) has risen to a 33-year high of over 11%, thereby nullifying the positive effects of the indirect tax easing since 1989.

This adverse combination of persistent drag of the demand side, amid recurring domestic and global shocks, and a surfeit of supply-side impetus are at cross purpose. Hence, the crowding in effect has been a mirage. Private capital formation/GDP has continued to decline, estimated at 8.4% in FY22E versus 10.8% in FY19. It possibly has declined further to 7.8% in FY23E.

Private capex is increasingly guided by household consumption, global trade, market situation and technological changes. Rising demand uncertainty, contracting exports, early withdrawal of fiscal support, and declining profitability of companies have resulted in continued shrinkage in the share of private capex to 29% of the total capital formation in FY23 from a pre-Covid average of 37%. Thus, from the position of preeminence in 2008, the share of private investments is now lower than both the household and the government.

The fast-receding global post-pandemic bounties have resulted in a sharp decline in the net profits of non-finance companies. Hence, with the government continuing with fiscal tightening, there is a likelihood of simultaneous contraction in both public and private capex. Thus, with the government in fiscal conservatism mode, along with exports contracting due to global headwinds underway, and corporates conserving their cash balances, the burden on households will rise considerably, despite their fragility.

Thus, breaking the adverse macro spiral would need a major reset.

The current policy tilt towards incentivising capex in manufacturing should be replaced with a framework that encourages investments in services sectors. India's services sector employs over 30% of its employed workforce compared to 11% by the manufacturing sector.

Also, India's household consumption pattern is discerningly shifting towards services (50% of personal consumption expenditure) with durables and semi-durables contributing only 10%. These services include fast-growing labour-intensive segments like health, transportation services, logistics, education, and tourism, among others. The services sector has a greater potential of creating employment, income, and demand. Studies show that employment elasticity of manufacturing sector has fallen to -0.21 (growth in employment/growth in output) while that of non-manufacturing is still positive (+1.26).

A switch back to progressive tax regimes by reducing reliance on indirect taxes, and through cutbacks on taxes on fuel and basic consumption items, can have a widespread positive impact on the demand side.

Protecting domestic industries through higher import duties or export subsidies helps select large firms, but it is not broad-based, unlike the growth buoyancy experienced during 1990-2012.

Increasing dependence on direct tax imposition will be beneficial. Corporate tax cuts in India (2019) and other countries have not resulted in higher private capex or growth. Recent research “Do corporate tax cuts boost economic growth?" by Gecherta and Heimberger, European Economic Review, June 2022 has shown that corporate tax cuts, on average, had no significant impact on economic growth. One can conclude the same for India as well.

Reducing tax exemptions for corporates and high net-worth individuals, cutting personal tax incidence on the lower-income bracket and lower indirect taxes may help in a K-shaped recovery situation.

These measures are attuned to breaking the prolonged negative macro spiral by aligning India to an employment-intensive service-led growth model.

A demand-driven policy construct should aid household disposable income and spending power at a broader level while compensating tax revenue losses through higher direct tax mobilisation. An upliftment in real disposable income can also enhance savings while simultaneously boosting demand for goods and services, eventually stimulating the private capex on the back of improved sales and sustained profitability, amplifying employment generation. The above prescription can potentially reverse the extant repelling demand-supply policy setup to a self-perpetuating cohesive positive spiral.

Dhananjay Sinha Co-Head of Equity and Research, Systematix Group.

The views expressed here are those of the author, and do not necessarily represent the views of BQ Prime or its editorial team

Essential Business Intelligence, Continuous LIVE TV, Sharp Market Insights, Practical Personal Finance Advice and Latest Stories — On NDTV Profit.