Good Time To Cut Rates On Small Saving Schemes | The Reason Why

The government raises the bulk of the money by issuing Treasury Bills for short-term needs and government securities for longer-term borrowing.

Every time someone opens a Public Provident Fund account, buys a National Savings Certificate or deposits money in a Sukanya Samriddhi account, they are also lending money to the government. For us, they are safe and long-term savings products, while for the government, they are predictable long-term borrowing products.

Over the years, this channel has become increasingly important for the government. But it has also become expensive. The government and the RBI are growing uncomfortable with the high interest rates on such schemes.

The Two Pillars of India's Borrowing

For most people, economists' obsession with the fiscal deficit can seem puzzling. The idea itself is simple: the government is spending more than it earns.

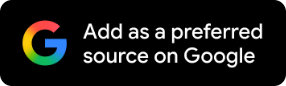

Once you look beyond this, how the government fills this gap matters more to everyone. The government fills the gap through two channels: market borrowings (75%) and small savings schemes (20-25%). All other sources, such as state provident funds, internal accounts, external debt, or drawdown of cash balances, are relatively small.

Market Borrowings: The Most Visible Channel

The government raises the bulk of the money by issuing Treasury Bills for short-term needs and government securities for longer-term borrowing. Banks, insurance companies, and mutual funds buy these bonds. If bond issuance rises sharply, yields tend to move up, making borrowing costlier not just for the government but for everyone else in the economy.

This constraint explains why the share of market borrowings in deficit financing has gradually fallen — from about 89% in FY11 to roughly 74% in FY26. The shortfall has been filled by a quieter, less visible source: small savings.

Small Savings: The Emerging Hero of Financing

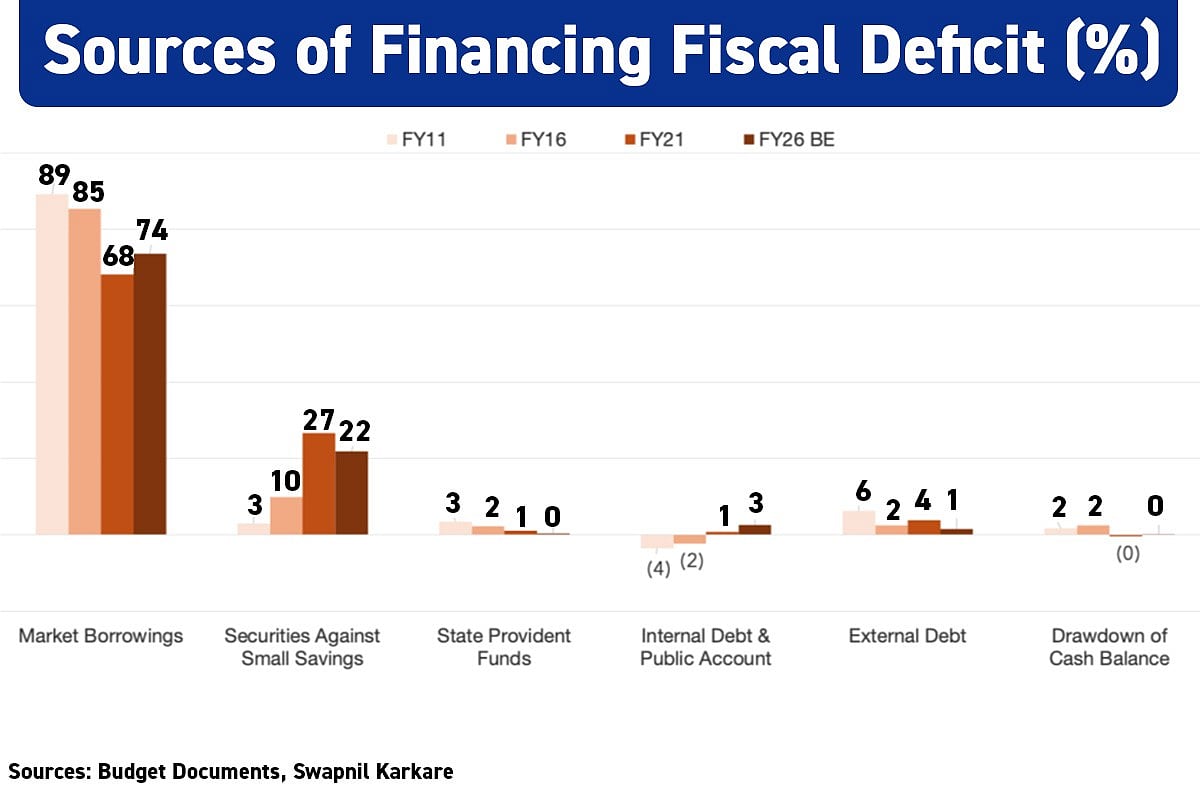

Funds mobilised through small savings schemes such as PPF and NSC are pooled into the National Small Savings Fund (NSSF), which in turn invests in special government securities. The share of securities against small savings rose from 3% of deficit financing in FY11 to 22% in FY26.

Small savings are attractive to the government because they are stable and largely insulated from daily market volatility. But they come at a cost. The government sets those rates, which are typically higher than government bond yields and bank fixed deposit rates.

What is often overlooked is that these rates are supposed to be market-linked. Following the Shyamala Gopinath Committee’s recommendations, small savings rates have been officially linked to government bond benchmarks since 2016 and are meant to be reset every quarter. In practice, they have not been changed for seven straight quarters. According to an EPW study, as of Q3 FY26, rates on these schemes were 1.13-1.44% higher than their formula-based levels.

Deposit Substitution, Banking System Effects

This rate gap doesn’t stay on paper. It changes how people save. The EPW study shows that when small savings rates are just 1 percentage point higher than bank deposits, the share of new savings moving into these schemes rises by about 1.2 percentage points.

This means that due to higher interest rates on such schemes, savings move out of banks and into instruments like PPF and NSC. Banks and RBI don’t like that. Banks are forced to keep deposit rates high to prevent outflow. That increases their cost of funds, making it harder for them to reduce lending rates. So even when the RBI cuts the repo rate, banks find it difficult to pass on the full benefit to borrowers.

Scope To Reduce Small Savings Interest Rates

However, this substitution effect appears to have limits. As Madan Sabnavis of Bank of Baroda notes, investment caps on schemes like PPF and SCSS, and the lower popularity of post office deposits in urban areas, constrain large-scale migration.

This is reflected in the data. Net additions to small savings have stagnated at around Rs 3 lakh crore a year recently. This means that even with higher interest rates, inflows have not risen meaningfully.

Final Take

Taken together, this tells us two things. Higher interest rates are not translating into proportionately higher collections in NSSF. Secondly, modest rate cuts may not cause a sharp fall in inflows, since participation is shaped more by scheme benefits, caps and demographics.

A long pause lasting several quarters only strengthens the case for linking these rates more closely to the market. That means, interest rates on PPF, NSC, and other instruments could fall if the government decides to go ahead with it. Yes, even I would be disappointed to see PPF rates come down. But deep down, that’s better for the economy.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of NDTV Profit or its affiliates. Readers are advised to conduct their own research or consult a qualified professional before making any investment or business decisions. NDTV Profit does not guarantee the accuracy, completeness, or reliability of the information presented in this article.