▲ Featured in Bloomberg Businessweek, July 15, 2019.

Subscribe now.

▲ Featured in Bloomberg Businessweek, July 15, 2019.

Subscribe now.

Inspired by Studs Terkel, Liao Yiwu, Svetlana Alexievich, and other writers, I recently spent six months traveling across five continents hearing the stories of working-class people from the millennial generation, particularly those in occupations that didn’t exist a generation ago. Some of them I met thanks to old-fashioned providence. One afternoon, wandering through Accra’s Agbogbloshie market, I happened upon Desmond Ahenkora, who resells used computers sent from Europe and the U.S. Other subjects came through formal channels. In Suqian, China, I met Shi Jie, a call-center manager at the online retailer JD, through the company’s public-relations department. In many cases, local journalists sought out interviewees in advance and came along to the meetings to translate and provide cultural context and guidance.

I conducted interviews in Ghana, South Africa, and the U.S. in English, and did the rest with the help of interpreters. For the latter, translators also transcribed my audio recordings of the interviews into English. In editing the accounts, we cut many of the false starts and digressions that mark natural conversation, as well as my own questions and interjections. Although we aimed to preserve interviewees’ exact language, we sometimes edited for clarity, including moving material so information could be presented in a logical order. In a few cases we inserted clarifications or elaborations offered after the formal interviews.

All the stories are distinct, but they also reflect common experiences of the great convulsion Muro describes. Decent jobs are flowing to big cities, with millions of workers leaving their ancestral towns in anxious pursuit, often slipping past national borders to do so. The internet is exposing people not only to opportunities that were once out of reach, but also to the unsettling knowledge that other people have many more. And the stories confirm that to be working class is, by and large, an insecure state. Superiors view labor as replaceable. Speaking publicly about one’s job can invite reprisal from an employer—or a government.

These 10 people felt they had stories worth telling, despite their often vulnerable positions.

| Lamine Bathily | 29 | SIDEWALK VENDOR in Barcelona, Spain |

| Phoo Myat Zin Maung | 25 | SEAMSTRESS in Yangon, Myanmar |

| Anonymous | 35 | ABALONE POACHER in Cape Town, South Africa |

| Fanny Tobon Tobon | 37 | MARIJUANA GROWER in Rionegro, Colombia |

| Trinh Thi Viet Ha | 28 | CAREGIVER in Kyoto, Japan |

| Desmond Ahenkora | 29 | COMPUTER RESELLER in Accra, Ghana |

| Nguyen Thi Ngoc Bich | 24 | ELECTRONICS MAKER in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam |

| Omar Elhaj Ibrahim | 34 | WAREHOUSE PICKER in Hamburg, Germany |

| Maya Kelley | 26 | SOCIAL MEDIA INFLUENCER in Brooklyn, U.S. |

| Shi Jie | 32 | CALL-CENTER MANAGER in Suqian, China |

With Anne Cassuto in Barcelona, Aung Naing Soe in Yangon, Kimon de Greef in Cape Town, Jorge Caraballo Cordovez in Rionegro, Yuki Yamauchi in Kyoto, Francis Kokutse in Accra, Trang Bui in Ho Chi Minh City, Mohammad Khalefeh in Hamburg, and Maggie Li in Suqian

Reporting for these interviews was supported by the McGraw Center for Business Journalism at the Newmark Graduate School of Journalism at the City University of New York.

| SIDEWALK VENDOR | Spain | |

| Lamine Bathily | 29 | Barcelona |

Photograph by Iris Humm for Bloomberg Businessweek

Photograph by Iris Humm for Bloomberg Businessweek

I was a rebellious child. I was always complaining in school, and they would punish me by not letting me play outside. I always wanted to talk in Wolof. I didn’t like to feel obligated to speak French.

• Pateras are small boats used to ferry migrants to Spain

My father sells shoes. He doesn’t have a store, he sells them in the market. During the holidays, my father would send me to my aunts and uncles, but that year I told my dad I didn’t want to do that, I wanted to help him instead. So my dad was super happy. He didn’t know I was planning to leave Africa. Because I was super young, people would ask me, “What are you doing selling things on the streets?” I would explain I was paying for my studies, and people would say I am so responsible for such a young person. My dad would always tell me I was going to be the best seller of all time.

I was working for my dad selling shoes, saving money, for a year. After a year, I went to the south of Senegal, and I decided to take a patera. I told my dad I was leaving to visit my grandmother for a month, so he wouldn’t worry.

Oof. It was an experience I would never do again. It’s very dangerous. You’re in a small boat in the ocean with large waves, and sometimes there are big boats coming. The last day we had no more food, no more water, and no gasoline. We were in Spanish waters. At 5 p.m. we noticed a helicopter in the sky, and we all started screaming for help.

My friends showed me where to buy more in a huge Chinese depot. You have to buy a large amount for them to bargain on the price. Oof. I arrived there, and there were many stores, and it was very large, and everyone knows how the Chinese are. You see them and say, “Oof, these are the Chinese.” So you just buy, and you leave. You never know what’s going to happen with the Chinese, they can change their mind from one moment to the next. I bought nearly 50 sunglasses my first time. My friends came together to help me, and they loaned me money for the glasses, on top of letting me live with them for three months without paying anything.

When the whites come to my country, they say how much they love you, and they come near you, but when you come here, everyone avoids you. Over there the police wouldn’t follow me, but here they’re after me, especially because selling on the street isn’t legal. You can get fined or even go to jail. When the cat is around, the mice don’t go outside. When police were arriving, someone would say in my language, “Get up, get up! They’re coming!” There is one mantero who goes out, checks everything, and comes back to tell the rest of us. He’s like an expert, because he knows all of the undercover cops.

I left the sunglasses and began to sell watches. That’s when I started getting into trouble with the police. They stopped me many times for them. One time they told me, “We’ll let you go without trouble, but we’ll take all of your watches.”

After a while, a year or two later, I started to feel like the leader. Other people were leaving, and many new people came. I started teaching all the new people, and I became their leader. In 2015 one of our colleagues died. The police told me the man jumped off a balcony. I didn’t know him personally, but he was a mantero for a long time, and we don’t believe that he jumped. We decided to organize and use our voices. We said, “From this day forward, if the police come, no one is allowed to run. We will gather our things and leave without running. If the police acts out on one of us, we must defend ourselves.”

It’s like this—if I don’t explain my story to you, you won’t be interested in me. We made multiple speeches in different areas, explaining why there are manteros in the streets. Manteros don’t want to be street vendors. A lot of people don’t know this. The thing is, no one wants to be exploited.

As a street vendor, you have to change your livelihood. At 40, no one likes to be chased by the police. With the moves I’m making—working three days of the week, and all the speeches we are doing—with all this I can survive.

| SEAMSTRESS | Myanmar | |

| Phoo Myat Zin Maung | 25 | Yangon |

Photograph by Chiara Luxardo for Bloomberg Businessweek

Photograph by Chiara Luxardo for Bloomberg Businessweek

I was born in a small village on Haing Gyi Island, in the Irrawaddy Delta region. Our township is located on the edge of the country and closest to the Bay of Bengal. In my childhood, it was so much fun—I remember a lot of things. I can’t describe one event as a special event, because every moment is special for me. But it has changed. We visited Yangon just before Cyclone Nargis happened. Then we realized it had happened, and we never left Yangon. Some relatives passed away during Cyclone Nargis. Some of my friends I haven’t seen since. Their villages were wiped out.

I joined this job because I need money. So in the beginning, I just thought about getting paid. But gradually, I didn’t really like it. Working at a garment factory is like living in prison. We have no freedom, we can’t leave whenever we want. We’re not allowed to take days off. And we have very long working hours. Some factories won’t hire laborers who are older than 30 years old. They’ll use our energy when we’re young, but not anymore once we’re aged. It’s like we have a dead life. It’s not OK. Now I know only this job, and I can’t really change the job. I don’t have self-confidence.

All the clothes I’ve made are to export to foreign countries—I’m not sure where, exactly, but the factory is owned by a Chinese owner. I also don’t know the brand, as they put the brand labels on somewhere else. I’ve mostly sewn jackets and pants. I’ve never worn these kinds of big jackets, because Yangon isn’t that cold. I have no idea what kind of person will be wearing the clothes I’ve sewn.

Supervisors and leaders are pressured by the boss. They’re scolding us every day. We’re sewing pants. The target is 100 per hour. I think it’s a lot. There are 70 people in our group. And there are different points—attaching pockets, zipping, buttons. While making these pants, I have to fill a lot of gaps. If someone can’t finish a hip or anchor point, then I have to fill in. Some people, they don’t go to drink water or to the toilet.

I have one elder sister and one younger sister. We’re living at a hostel nearby, all together. My elder sister is studying at university, and the younger one is at her middle school. My mom is a tailor.

My mom couldn’t work a lot after she got in a motorbike accident. When the accident happened, I was at the factory. She was at the traffic light, and the cars were stopped, so she was crossing the road, but a motorbike hit her. I found out about it only when I arrived back home, because I can’t use phone at my work—it’s kept by leaders during working hours. Her hip bones were cracked, and she had to receive a monthlong treatment at the hospital in Hlaing Tharyar Township. She had to continue resting in bed for one or two months after she was discharged.

It got more difficult because of the accident. But now we’re used to it. My sister is also sewing more. It is not like we’re fine, but we’re OK. We can afford to eat and live. My hostel costs me around 50,000 kyats per month. We also have to buy water, food, and other necessities for daily use. So we need 400,000 kyats per month. This is without emergency health costs. My sister gets, like, 150,000 kyats. We’re forced to work overtime, so I get around 220,000 kyats a month.

Now I’m a graduate. I studied history at the University of West Yangon. Our distance education is nothing special. We got only 10 classroom days within one semester, then we had to go for exams. So we had to learn by ourselves. The problem was I couldn’t study because I was working all day. It was all my fault. My subject, history, is really interesting. But when I came home from work I was already so tired and had to go rest, and had to get up to go to work at 8 a.m. If I cooked for myself, I had to get up at, like, 5 a.m. I couldn’t learn well. But I had a chance to learn something that I didn’t know before.

I like traveling, and I want to explore new places. I want to be a tour guide. What I’m sure of is that I won’t be working at the factory in the next five years. Even in Myanmar, there are many places I haven’t been. If I travel, I don’t like just visiting or being a tourist. I like to understand local cultures as well. I want to know details about the place. If I have a chance, I would like to visit Rome.

| ABALONE POACHER | South Africa | |

| Anonymous | 35 | Cape Town |

Photograph by Charlie Shoemaker for Bloomberg Businessweek

Photograph by Charlie Shoemaker for Bloomberg Businessweek

I got fascinated by the sea, by the sea life. When I grew up I see people catching crayfish here with the canoes. I decide, well, I’m also going to try. You know, a door of a fridge—it’s floatable. On our knees, with our hands in the water—that’s where I started. I was 12, 13 years old. I’d sell it here, to the foreigners. Stand here in the grass, and then sell them big crayfish. Thirty rand each. I still can remember, the first 30 rand I got, I went to my mommy: “Here, mommy, buy you a packet of cigarettes.” So she can’t yell at you: “Why you catch crayfish?” She’s happy now. I can go again.

• Abalone is a mollusk that’s long been a delicacy in China. A beloved but threatened variety found off the shores of South Africa is increasingly being poached.

As years go by, life is getting more expensive. Today’s world is very expensive. That’s why we poach, to make a living. Every day we can get bread. Other people think we stealing. It’s the sea! God gave us the sea!

You just get in the cold water, down there, and get what you want, it’s free. I don’t feel the cold. Down there my mind is nothing, just: Where’s the abalone, where’s the abalone, where’s the abalone? If you see one, you must always look around; the family is there. You need to study their breeding grounds, the feeding grounds. I know him by now. I know him. You just take a good look: Oh, it’s you.

I won’t forget that. On the island walking around, looking for water. This big snake! Saw it there. Seen empty cannons, big cannons! Antique history cannons. There’s nobody here on this island! What happened here? Like a hurricane came through here! I need to get something to drink. My mind doesn’t go anywhere. I don’t worry about Mandela.

There was no water. Only place we can get water is where the police is, ha! So me and my friend turned ourselves in! I got seven days in prison for that.

It’s worth getting caught for. Every guy in this place, in Hout Bay, it’s in his veins to be a diver.

Wind was blowing! Hsshf, hsshoof! Come around the mountain, I see all these things in the water, just orange, orange, drifting. I see that boat there on its side, it’s turned over. I see kids, babies, old man! There’s an old man already dead. I told that other diver, “Leave this guy, he’s already dead! This old man is dead here!” People was screaming: Yeaaah! Old ladies, and children—I first went for the children. All of our divers jump to the water—picking them up from the water, swimming with them, on the boat, fetch another one, swimming with him, on the boat, then another one, swimming with him, on the boat. We brought all that we could.

I don’t save. I don’t save anything. I got my child to support, mom and my dad. I’ve got a buying sickness in me, I dunno! If I got money, I buy anything. I’m a money spender. Music systems, shoes, jewelry, anything. Then I get f---ed up, then I party. But that’s the last thing. First my baby, my mom. Then me. I don’t even know how to work a bank. I keep it in my pocket, my friend!

You will never stop us poaching, never, ever, ever, see. In our minds, f--- their concerns, ’cause this is our place, that is our bread and butter. Talk about extinct and shit, f--- that. Still lot of abalone there. Taste like the sea. I eat it, but I’m not actually fond of it. I still wondering, why is this species so expensive, why, why, what’s making it so? I don’t know, maybe the Chinese make medicine, make penis enlargement. I don’t go deep, as long as the money’s right, I don’t worry what you do with the abalone.

They send people that never ever seen a sea before, never ever seen an ocean before, to tell us been living and breathing of this ocean we not allowed to catch this. Who are you? What do you know about these fish, huh? It’s something you can’t explain, man, you must explore it yourself. That’s it, you must go down there and see for yourself. What surprised me? How alive it looks down there. Alive.

| MARIJUANA GROWER | Colombia | |

| Fanny Tobón Tobón | 37 | Rionegro |

Photograph by Nadege Mazars for Bloomberg Businessweek

Photograph by Nadege Mazars for Bloomberg Businessweek

I grew up on my grandfather’s farm. It was a beautiful childhood. I learned to ride horses, to milk the cows. My dad taught us that there’s no job women can’t do, and that our own mind is power, and we can achieve a lot of things.

Those were very violent times, so we were displaced, and we came back to San José. I worked for a while cleaning houses in Medellín. After my dad died, I was in charge of my little sister, my mom, and my daughter. So I decided to look for a job, and my mom helped me, taking care of my daughter. I could only see her during the weekends, and I called her during the week.

I worked on chrysanthemum farms. After a while, I met another person in San José, and we were together five years. I had my second daughter with him. But he was murdered when she was two and a half years old. The violence. Only human beings with memories are left. It’s not easy to raise your children without their fathers, but I explain to them that God is the owner of our life. He knows when we come and when we have to leave.

So I was by myself with my two daughters. But I don’t let adversities sidetrack me. After a while, I met another guy, and I married him. I’ve been eight years in a stable home with him, and I had two more children, a daughter and a son. My husband is a blessing. He has a very beautiful way of seeing the world. He is serious, responsible. With my daughters he’s had a very important role as a dad. He’s a warehouse assistant in a big chocolate company in Rionegro.

I think I’m a very strong mother, especially since 2015, when I faced a very hard experience with my second daughter, who was 11 years old. I was at home preparing dinner, when she went to the store to buy some sausages. A guy on a motorcycle came fast down the street. He hit her and sent her 7 meters.

Two boys told me, “Stefa was hit by a motorcycle, and she is dead on the street.” I had my 6-month-old baby in my arms. When I arrived, my daughter was convulsing. Her head was bleeding. Then a man in a car stopped by and asked me, “Are you going to let her die? Jump right in, I’ll bring you to the hospital.”

She was in a coma for two months. One day I arrived at the hospital, and they explained that my daughter showed brain death. They asked, “What do you think about organ donation?” But God has her here for a big reason, because she woke up. The mind is super powerful, and you can do many things. I used to tell her, “Please don’t ever think that we’re not going to make it. We’ll make it.” I used to read to her, I held her hand to write with her. By then, I’d been growing chrysanthemums four and a half years. But I said to myself, “If God kept my daughter alive, it’s because he’s going to help me with all that will come after this.” So I quit my job, and I decided to devote myself most of all to my daughter.

She’s aware she can’t understand things as she used to. She attempted suicide a couple of times. So I decided to take her to school only one day a week. I also registered her in swimming classes. She goes to painting classes because she wants to be an artist. The fact that she had this serious accident doesn’t mean she isn’t capable of doing many things.

My sisters asked me, “Fanny, are you sure that it’s legal? That it’s viable? That it’s going to be OK? That it actually is what they say it is?” And I told them, “Yes.” Now they’re excited about it.

I work with the mother plants. They’re called mother plants because you take the cuttings from them. Then I take those cuttings to a confinement area where they’re sown. You walk along the bed. You take 60 cuttings, you spray them and put them inside a bag. Then you place four of those bags in a small box. Then a colleague will take that box and take it to a cold room. My job in the flower farms was very similar, because chrysanthemums are also in beds, and you do the cutting from the mother plants. To propagate the plants from the cuttings is like being a mother. You help them grow, and you have to take care of them every day.

The smell stays in your clothes. It’s a new fragrance for me. My youngest daughter said, “You smell weird,” and I explained to her that the plants have a strong smell. My oldest daughter asked me, “Mom, are you going to get hooked on marijuana?” And I answered, “Of course not.” I was a very focused girl, so it never occurred to me to try cannabis. I want my children to see me as a good model. Here at PharmaCielo, they’ve taught us about cannabis’s benefits. I’d love if my daughter could be treated with cannabis, because that’s what I’ve always looked for—that she doesn’t have to be treated with so many different medications, because that brings a lot of consequences. That’s my dream, to help a lot of people and also find my daughter’s well-being.

We had a calamity in my house last December. There was a fire because of a short circuit, and a lot of our belongings got burned. That day I’d left work with the kind of hope I believe all moms have. They had called me for a meeting about a new housing project. I called my second daughter, and I asked her if she was afraid to stay alone at home with her 5-year-old sister. And she told me, “No, Mom, go to the meeting. I’m fine.” When the meeting ended, I called her again. She told me that everything was fine and that her younger siblings were already in bed. But when I arrived home I saw everything on fire. A neighbor was helping to fight the fire. And my daughter was in shock. It was painful because you can imagine all the time that I spent taking care of her, and that night she was the one who had to deal with the situation. She says, “It was no one’s fault, Mom. This was just something that happened.”

I think everything that’s happened with her, all those things we’ve been through, they’ve made us stronger and helped us to grow as a family. Material things are given to you by God, but he also takes them away. There are more beautiful things in the world. There are some people that attach themselves to a car, or to some trips, and they don’t realize that happiness can be in going out with your family to eat an ice cream. In this moment we are trying to stabilize many things. If I keep working, we can solve them slowly. Right now we have a tight budget because we’re late paying debts. But every day we wake up with the conviction that we’ll overcome this. God has great things for us, and here we are.

| CAREGIVER | Japan | |

| Trinh Thi Viet Ha | 28 | Kyoto |

Photograph by Shiho Fukada for Bloomberg Businessweek

Photograph by Shiho Fukada for Bloomberg Businessweek

My parents used to run a company. They processed seafood such as fish, crab, and shrimp. The economy opened up in 1986. As Vietnam’s political system changed to a new one, my parents’ company changed from state-owned to private. They had to get training to continue with their business. But my mother was pregnant at the time, and my father couldn’t go either, because he couldn’t leave his pregnant wife alone, so they gave up. They gave it up for a child, which was me.

I got interested in Japan after I applied, and I learned about Mount Fuji, matcha green tea, and Japanese culture. I was intrigued by kabuki because the faces looked so scary, and I thought the fall foliage was really beautiful. After being accepted, it was required that we study Japanese for a year and take a Japanese language proficiency test. The classes were for eight hours a day.

I came to Japan on June 6, 2014, with 137 graduates of the same school. There was no trash or traffic jams. Everyone was very quiet. I worked at a care facility in Kobe. I was assigned to work with residents who lived in the facility year-round. My work was to help with their bathroom needs, bathing, eating, and so on. I had to report everything each resident did for the day. For example, I would write if I noticed he or she had something unusual on their body, they could swallow food smoothly, they coughed a little, how they did at the bathroom, and so on. My Japanese skills weren’t great at the beginning.

I learned a little bit about Japan’s demographics, that there were more elderly people and fewer working-age people. In Vietnam there are only a few care facilities, and they’re very expensive, and people don’t really know about them. They consider children taking care of their parents to be just the way it is. In Japan, if their sons go to work, and if their wives work, too, and the children are in school, then they just don’t have anyone taking care of them. Care work isn’t a popular profession because it’s tough. You have to love taking care of the elderly people.

During the first year, I was known as very energetic and talkative. So the managers thought it would fit better for me to work with the day care patients. Many of the long-term residents were in wheelchairs or bedridden, but the day care patients could swim, walk without any problems, and talk a lot.

The boss was really good at communicating, and the blind lady trusted the boss. My boss decided to explain to her a lot about me, and would tell her how I wasn’t noisy, I’d learned Japanese in Vietnam and come here, I’d been through a lot, my language might not be perfect but please teach her, and so on. She said she wanted to go for a walk with me and chat with me. She apologized for what she did, too.

She liked singing and dancing. Even though she couldn’t see, she could move her body a little bit. After spending two or three weeks walking and singing together, she ended up really liking me. She loved coffee, so I would ask her if she’d like a cup of coffee when she arrived every morning, and she was happy that I remembered she liked coffee. You wouldn’t ask someone to do something if you don’t like that person, right? She asked me to do a lot of things.

I followed what my parents said in Vietnam, but I came to Japan and I felt free. I felt I could do whatever I wanted, nobody was watching, and I liked this way better. I love it here.

I got married. He lives in Kyoto. He works for the government at a water treatment facility. We met in January 2017. We didn’t get married right away. We dated for about a year and half and learned about each other. When I told my parents about him, they were surprised. Marrying a Japanese guy meant I would live here forever, I would have to learn Japanese culture as a wife, which would mean I’d have to learn how to cook Japanese food, build relationships with his family, communicate well, and so on. They felt they would be able to help me if I got married in Vietnam, but they can’t help out with anything since I’m in Japan. They told me if I married him, I would have to work hard even if it was difficult, because they wouldn’t be able to help, so I said I’d be OK, I’d work hard, and they allowed me to go down this path.

I just moved to Kyoto. My husband said I don’t have to work until I get settled. I’m still thinking about what I should do. I listened to my parents without questioning before, because I was little. I didn’t know any better. But now I live and work in a different country, so I have to make decisions by myself. I just seek advice from them. They ask me for my advice, too. We are like friends now. We are equal. Maybe it means I grew up.

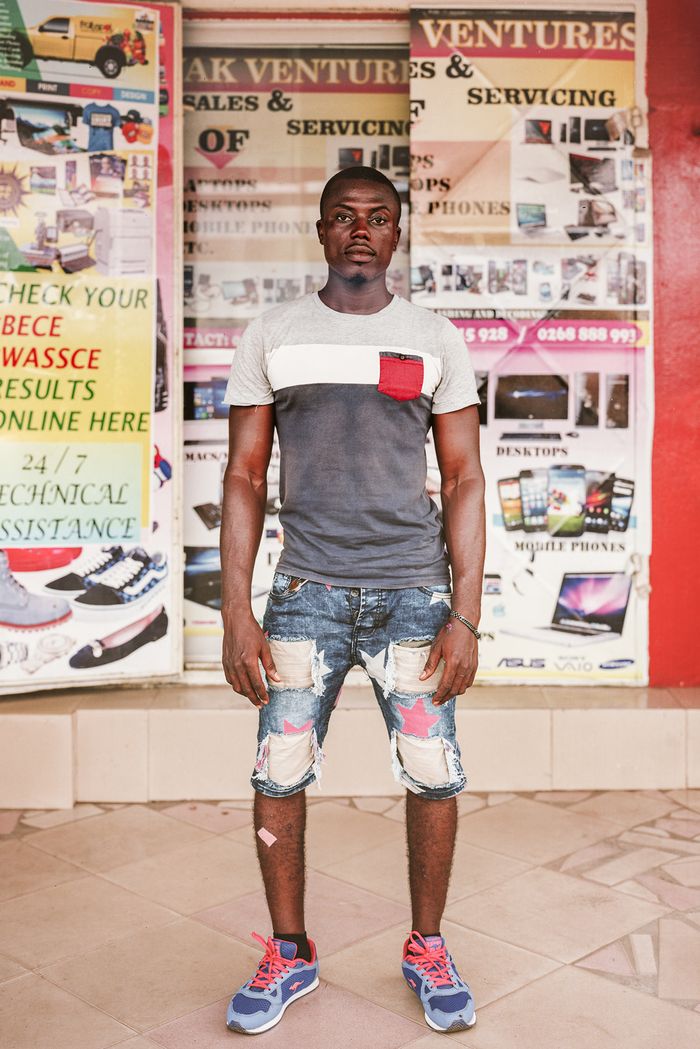

| COMPUTER RESELLER | Ghana | |

| Desmond Ahenkora | 29 | Accra |

Photograph by Ruth McDowall for Bloomberg Businessweek

Photograph by Ruth McDowall for Bloomberg Businessweek

People here, if you come here with such questions, normally they don’t want to answer—although you explain yourself, that you’re a journalist, that you want to publish an interview, blah blah blah blah. But I will tell you a few things about me.

• 1 cedi = 18¢

My mom, my dad, all my siblings, they are all here. They ran drinking spots—like, pubs. I was sent to the technical school. I was studying automobile engineering. We were boys, no money. One of our boys bought a computer. This one would go home and use PowerPoint to do some design and bring it to school, and we’d be watching it. We were all interested. So this is where it all started. I was working for my parents, and I told them that I need a computer for my classes. With their help, and with my help, too—I was in my father’s spots, selling drinks—I bought my computer. We’d dismantle the whole thing and reassemble it back. We were interested in opening it and knowing much about it.

In 2013 I made up my mind that I had to learn driving. I had to get money to do my driving license. So I sold that computer to a friend. I started. It was very stressful. Somebody owns the taxi, and you take it to work.

You have to think, because there is nothing for you to do. If you go and work for somebody who will pay you, for the whole month, 300 cedis—it is not enough. Because you eat. And what of your clothes? What of your room rent? What of your utility bills? You have to think about it all. You see? If you are hungry in your room, you’re thinking plenty. So this is where I decided to, you know, think different.

I go to a certain shop, they were selling computers. I told them, “I want one of these machines.” I think it was a desktop HP. They were selling it for 300 cedis. I bargained with them to, I think, 170 cedis. I took it home. So I take the photographs of the particular machine, and I take the specifications, and I posted it online. A client came to me at home, who bought it from me. I was able to make, I think, 130 cedis.

You have to use your small brain. On Facebook, if you post, your friends will see, and one friend buy one from you, he can recommend you to another, and you’ll be adding friends. I’d be driving, and I’d be posting. The only things I need is the picture of the product, the details of the product. When the buyers call, they also bargain with me. If I get 100 cedis, 200 cedis on it, fine.

Sometimes they want to upgrade: I need memory, I need power supply, I need this, I need that. When it is bashing you—I mean, it’s giving you a tough time—you Google the problem. Maybe someone has a video on YouTube.

With IT, I feel happy. I think that’s where my passion is. My parents, they are still running the pub. Life goes on. The lands are still there. Since I came to Accra in 2006, I have not been going back. Maybe this year I’ll be going there. It’s been a long time. IT is taking over the world. If you go there, they don’t know that stuff. When we went to school, we used to study IT, but there were no computers. They’re just doing the theory, rather than the practical. They would just draw it on the board for you. How can you study something, and you don’t even know about it?

If I get some money, I’ll go back home and open shops. If I’m rich, I’ll even open an IT school. I have a whole lot of plans. A whole lot of plans.

| ELECTRONICS MAKER | Vietnam | |

| Nguyen Thi Ngoc Bich | 24 | Ho Chi Minh City |

Photograph by Olivier Laude for Bloomberg Businessweek

Photograph by Olivier Laude for Bloomberg Businessweek

I’ve been working here quite some time. If there’s a person who’s having a day off, I’ll replace them. I know about more stages than the average worker. Not everyone who works here a long time could do that. Instead of five, six people working on one product, I could do it by myself.

I was born in the Mekong Delta, Dong Thap province. We kids would swim in the river, because we liked water. My parents didn’t have land, nothing. I didn’t start school until I was 8. I was there just four to five years, then I had to start working. I joined about two, three factories before this one. I was underage, so I had jobs that didn’t require a lot of documents, just temporary jobs. I worked at a garment factory in my hometown when I was 15. Then I worked at a shoe factory. I was 16, 17 then. My father was an alcoholic. I was rather disheartened. I didn’t want to stay at home.

There was a person in my hometown who worked at this factory and wanted to introduce me. I thought I could do it, so I just left. My acquaintance brought me to the factory and showed me where to file my application. Then, immediately, there was a person interviewing me. They trained me for two days. On the next day, I started work. I’ve never seen such a clean company before. They have uniforms and air conditioning, better than many places I’ve worked in. When I was 17, I didn’t have a contract. The company could fire me whenever they wanted. But after they saw that I could do well, they signed an official contract with me.

We have two weeks of day shifts, followed by two weeks of night shifts. I’m used to hardship, so I don’t have a problem with it. Other people might complain that they’re tired. They’re used to eating well at home, so they think the company’s food isn’t as good. But for me, it’s better than the food at home.

There are many kinds of products. Every once in a while, my bosses would say, It’s for automatic eyes—when you hover your hands near it, it’ll release water, or when you push the button it does something. Not exactly that. I should know what it’s for, but there are so many kinds, after a while I can’t remember which one is for what. It’s my daily job, I just need to finish it. I can’t remember much about those products.

I was like this since I was born: I wanted to take care of my family. If I don’t do it, no one will. So I have to try my best. I’m trying to take care of my mother and my younger siblings. My dad only drank. He didn’t make any money. I don’t have a problem with my dad drinking a lot, but the thing is, he always yelled and swore at us. As I got used to it, I felt sad for my mom. My father died a year ago. My mom is doing well now, but my younger brother and sister are not mature yet; she can’t leave them alone.

I work in Saigon. I could have dressed better and eaten better, right? But I didn’t. I thought, I shouldn’t buy stuff or go out, I should try to save money to send back home for my mom.

Back home everyone thinks I must enjoy my life. But if you just work for money, then no job is easy. There are many beautiful places in Saigon I haven’t gotten to go yet. When I was young and single, I really wanted to. But I’m weird—I would think about my younger sister who didn’t get to go, so eventually I just didn’t go. I really wanted to, but I didn’t. I’ve been living in Saigon for seven, eight years. When I got married, I thought my husband would take me out, but then we had a baby, and we still haven’t really gone out. I really like Dam Sen Water Park. I’m a bit childish. I like waterslides and such. I’ve been there once, and that’s the only place I’ve been in Saigon.

| WAREHOUSE PICKER | Germany | |

| Omar Elhaj Ibrahim | 34 | Hamburg |

Photograph by Alexa Vachon for Bloomberg Businessweek

Photograph by Alexa Vachon for Bloomberg Businessweek

I was born in Raqqa, Syria. We are six brothers and two sisters. My dad worked as a contractor. My mother is a housewife. We were very close-knit. I have a brother who studied electrical engineering in Moldova. He’s the person who affected me most. He taught me how to play chess. He sat at the board, and he started explaining it to me as something that’s very logical and doesn’t count on luck.

I did not like education in Syria—the teachers, I didn’t like dealing with them. My mother would say that this is a phase, and it will pass. At 16 years old, my choice was to study economics, and the whole family was happy.

My father was in Libya, and he had hernia surgery. However, a medical error was made, and my father died due to the anesthesia. That really broke me, that my dad didn’t see me graduating, growing. After he died, my friends felt that I had to work. My friend spoke to a company called Al-Haram in Raqqa. It’s in money transfer. He talked to the manager. He said, “I have a friend, Omar, he’s an intelligent guy, he knows what he’s doing.” So he asked, “Who is he?” He told him, “His name is Omar Elhaj Ibrahim.” In Raqqa we all know each other. So he asked him, “Omar Elhaj Ibrahim, he’s the son of whom?” So he told him, “This is the son of Bashir.” So he told him, “Let him come to me.” And so my father helped me, though he had passed away.

I became a teller. I was responsible for counting the money. I would give the money to people. After a while, I became a manager.

I have two brothers, the eldest and the youngest, who were in Turkey, and my mother would visit them. She told me, “What do you think about going to Turkey for a visit?” I noticed that she was packing and cleaning the room, she was packing and cleaning the whole house. I made an excuse not to go to Turkey, I told her, “I don’t have any money.” She told me there’s no problem, she told me, “Choose your clothes.” So I told her, “How long will we stay?” She told me, “About three weeks.” It was 2013.

I was talking with my brother—the brother here with me in Germany. He was telling me, why am I not communicating with our mother, why am I cutting conversations short with our mother? I never told her that I was hungry. I got angry. While I was under this kind of pressure, I didn’t want anyone to see me. The phone broke. I was sitting on the bed, and there was a chair in front of me—when I hit it on the chair, it broke. So I got this iPhone. I didn’t have enough money to pay off the iPhone, so I had a debt.

I was eating a lot of potatoes and eggs. I tried to go to employment offices, but our personalities clashed. I wasn’t looking for a job in the black market. I knew this was a phase that would pass. Someone told me about Amazon, and he gave me a location where the interview would be. Four days before, or five, I opened Wikipedia. I had limited knowledge of Amazon. I was reading about Amazon—who is its founder, that it’s an electronics company. I read about it, and I prepared words in German.

I went. I spoke with the receptionist. Another employee came by. She took me, and we started the interview. She said, “What do you know about Amazon?” I explained to her something from what I’d read. She asked me, “Why did you choose Amazon?” And here I started acting: “It’s a good company, I see my future in it, and my specialty is economics, information systems.” I started talking to her about quality and agility. She even asked me, “Did you ever buy anything on Amazon?” I told her, “I’m not going to lie. I am poor, I cannot buy from Amazon.” My goal was to touch her heart. She laughed. She told me it’s not a problem.

I have to have a specific speed. In an hour, 300 articles. The robot comes, I take the article. For the first 15 days, I didn’t have the money to have lunch at Amazon. Lunch was coffee with sugar, so I would raise my adrenaline. At work I didn’t talk to anyone.

A week before my contract ended, I assumed that the company didn’t want me anymore. I didn’t go to work the last week, thinking they didn’t want me anymore. Why did I do this when I was in need of money? I had just lost hope. However, during the interview, I hadn’t put down my phone number, because I hadn’t paid the phone bill; I had put my friend’s number. They told my friend, and my friend told me, “Omar, they want you.” I went and signed the contract. They had extended it for me for a whole year.

I knew that I had to change my glasses. I went, and I bought them.

My monthly salary was €1,925, but I had taxes, so I earned, net, €1,350. After I finished one year, I started earning €1,500. Every week, my supervisor comes and tells me what I worked in one week, for example 75% of the target. If the percentage is more than 80%, that’s good. If it’s otherwise, they would ask why. In 2019, in Europe, there’s a lot of acting, no one will tell the other, “You’re stupid” or “You’re a donkey. You don’t know how to work.” So they’d ask, “Why? Are you tired?” These cold questions, with a very cold and rude smile.

In the pick, the biggest problem we face is that you stay by yourself for four hours. You can’t talk to anyone at all. If you noticed the shape of the pick, it’s a cage. After a period of time, it would make you think bad, negative thoughts. I wanted to make sure: Is this the case just with me or with everyone? So when I went to the bathroom, I’d ask my friends, “What are you thinking about? Are you being taken away by such thoughts?” One would tell me, “Yes.” Everyone had this problem.

Haspa is a common abbreviation for Hamburger Sparkasse, a major German savings bank. Today my plan is to quit and go back to school. This job, this isn’t what I studied and worked hard for. I will look for any company that’s relevant. I’m aiming for the Haspa. I have lost 7 kilograms. Why? Because you are making, in one day, a minimum of 2,000 movements, let us say. I have pain. But if a time comes when you bend, you should know: “The wheat stalk does not bow / If it is not burdened / But in the hour of its bowing / It hides the seeds of its survival / Concealing in the earth’s womb a coming revolution.”

The trauma of seeking refuge has hit everyone without exception. It’s the emptying of the self, the emptying of the self. [Addressing the interpreter, a friend of his who’s also a Syrian refugee.] You are Mohammad, but you are different from Mohammad, she is sitting with you, and she doesn’t know who you are, but you were a whole person in a whole family, you weren’t born a refugee.

When I first arrived, it was really cold here, and I didn’t have money, so I didn’t have clothing. It was hard. You have to come back to the real Omar. [Gesturing at his glasses.] Those? I chose them with my own hand.

Ibrahim left Amazon in 2018. A company spokesman said that he couldn’t speak to specific experiences, citing German privacy law, but that Ibrahim’s account “does not reflect the day to day reality in our buildings.” He said pickers have regular opportunities to speak to others, the warehouse near Hamburg has a manager responsible for employee health, and workers have avenues to air grievances.

| SOCIAL MEDIA INFLUENCER | United States | |

| Shamiyah “Maya” Kelley | 26 | Brooklyn |

Photograph by June Canedo for Bloomberg Businessweek

Photograph by June Canedo for Bloomberg Businessweek

I grew up in a small town in South Carolina called Irmo. It was a suburb of Columbia. My mom works at the post office, and my dad was a stay-at-home dad and had little side businesses. It’s not like I was super poor—just everyone else was so much more wealthy. Sometimes my family didn’t have enough money for food. I’d go to school breakfast, and I’d go to school lunch, and then sometimes there wasn’t dinner. Sometimes my parents were doing really well, and it was great, and sometimes they weren’t.

I always knew that wasn’t going to be my life forever. I didn’t know what the means to the end was going to be, but I was like, no, I’m not gonna stay in South Carolina forever. I think the theme in my life is that if I want something, I have to go take it.

Both of my parents are from New York. My dad’s from Far Rockaway. Mom’s from Jamaica, Queens. They had me when my mom was still in high school, and my dad had just graduated high school. Usually we would go back to Queens, so I didn’t even really feel like I was in New York City. But there was one summer that I did come to New York when I was 15. I stayed with my grandmother. I would go to Times Square and stay there until 6 a.m. I didn’t even go to clubs. I would just talk to random people, which is bad; you shouldn’t talk to strangers in Times Square.

That was what ignited me. I would always tell everyone, I’m gonna move to New York.

When I was applying for jobs when I first graduated college, I wasn’t getting any hits. I had “Shamiyah” on the résumé. I read a BuzzFeed article about some guy who had an ethnic-sounding name, and he wasn’t getting any hits, and then he changed it to something neutral, and he started getting hits right away. I changed my name to Maya on my résumé, and within a week I’d gotten a job. You’ve got to choose your battles. People who know me really well, from my childhood, they call me Shamiyah, and everyone who knows me in this new iteration of myself, they call me Maya.

My college boyfriend was in the military, and he’d gotten stationed in Virginia. I tried to pass my days by cooking and cleaning and doing domestic things. But I was just like, This is awful. I hate it, I’ve got to get out of here.

Then I ended up getting another job as an assistant for an influencer. I got to do a lot of creating content, learning all these things that help to make someone into an influencer. I’d been on Instagram, but I wasn’t really doing anything with it. Then I thought to myself, Wouldn’t it be cool if I posted a photo of my outfit every day? After work I would walk around and ask people who seemed nice, “Hey, here’s my cellphone. Can you take a photo of my outfit?” I put together a website.

After that, I worked at a media agency. They work with mom bloggers to connect them with brands for sponsored posts. I was like, all right, people are making a living off of this. Then a recruiter reached out to me. It was a PR agency, and they were starting a social media division. I ended up running social media for a number of restaurants, hotels, resorts. I had maybe 12 clients, all on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and Pinterest.

It got to a point where I was like, I don’t know that I’m really being fulfilled. I came to the conclusion that I was going to work on my blog full time. That was August of 2017. That meant, every single day, getting out there, shooting, and putting out a higher volume of content. I started to get more brands reaching out to me. That’s where the majority of the money comes from. On a regular basis, I’m going through and looking at my photos and looking at the top-performing ones and looking for trends. I’ve noticed that pink performs well on my feed. Also I find that the poses where I’m very casual do really well. I try to walk or sway a little bit, so it doesn’t look like I’m posing.

Sometime in the summer, I remember it was a very hot day, I brought my tripod with me, and I set it up on the Brooklyn Bridge. Then I climbed up on the little ledge. There’s a ton of people walking, there’s bikes zipping by, it’s hectic and chaotic. I’ve got my tripod taking up half of the bridge. I was there for a good hour, taking photos. I’m clicking, clicking, clicking, and then a biker zips by, and it startled me. I lost my little clicker, it just went overboard. That was a hard day. But the photo came out really well. I think it got a little over 700 likes.

I started to get more and more brands reaching out. I try to be strategic about what I’m accepting, even if it means I’m leaving money on the table. If suddenly my followers were to feel like, Wait a minute, she’s not being authentic—that’s the crux of being an influencer. Once I lose that, I don’t have any currency left. This one skin-care brand ruined my face. I broke out into hives. And then I got a chemical burn. I was out of commission for a month. I couldn’t do any sponsored posts. I reached back out to the brand: “Hey, I really appreciate you guys choosing me for this campaign, but I can’t in good faith move forward with it.”

My friends from high school, they’re like, “Oh, my God, it’s so cool, you’re living this glamorous life in New York.” No one sees the less glamorous part. I’m running around town, and I’m carrying tons and tons of clothes while I do all these different shoots. I do all that stuff by myself. I don’t have an intern or assistant. I’ll go to a Starbucks, I’ll go into a fitting room at H&M, and change outfits.

For sponsored posts, my minimum is $400 for one Instagram post. My first full year, I think I made about $40,000. Sometimes I have windfalls. And sometimes I’m stretched thin. Sometimes I have little side hustles. I do babysitting, I read to kids. I sell things on EBay. Not everybody can be the huge mega-influencer with a million followers, and that’s OK. I make a modest living. But I’m able to have freedom in my life.

My cousin, he works at Dollar General. A lot of the people from my life are just living very regular, ordinary lives. No one does what I’ve done in my family. Ex-boyfriends of mine, they’re just like, Who are you? Who’s this person? People say it’s a persona. My whole online presence is the idealized version of myself right now, but it’s still who I am. It’s like watching a TV show. They have to edit it down. I’m editing down who I am into this little package.

| CALL-CENTER MANAGER | China | |

| Shi Jie | 32 | Suqian |

Photograph by Bakas for Bloomberg Businessweek

Photograph by Bakas for Bloomberg Businessweek

I think my memory of childhood is pretty typical of the generation born in the ’80s: red-tile houses and dirt roads that would turn muddy once it rained. I would never have imagined I could now work in offices equipped with AC, because back then we didn’t even have electric fans. A handmade palm fan was all we had. My family lived under quite poor conditions. I was quite naughty as a kid and would often either pick a fight with the boys or go catch fish and shrimp with them.

One year my mom got really sick and passed away soon afterward. Losing one of the only two breadwinners of the family made all of the burden fall on my father’s shoulders. As the eldest child, I even thought about dying together with my mom. But my father said to me, “Even though your mom is gone, we’re still a family of four, with your little brother and sister. As the big sister, you should try to finish high school.”

After graduation, having known and witnessed how my father swallowed the sorrow of losing someone who’d always been there for him, I decided to stop school and take on my due responsibility to support my family. Relatives coming back from other cities told me that electronics factories in Changzhou and clothing factories in Zhangjiagang offered quite good salaries. So after convincing my dad, I took off for Changzhou to start my first job in life.

After I came back from Changzhou, my dad was thinking about finding me a husband. But I thought I should fall in love at least once in my life. Being able to spend time together and getting to know each other is what I wanted, rather than being introduced by others for the purpose of getting married.

I met my husband at a bigger JD warehouse that we later expanded into. It was around 2008. I’d gradually switched from the position of order picking to printing invoices. He used to work in front of me, and my impression of him was that he had a really nice personality and almost never got angry. Basically he would pass me the item after scanning, and I would print out corresponding invoices. Each day I needed to print a lot of invoices, which could be quite messy. Occasionally he stayed after work to help me tidy up. I considered him a very attentive guy, but he wouldn’t talk to me much because he was too shy.

One time I was having a bad stomachache, and my friend drove me to the hospital. The checkup result was fine, but I was still feeling pretty down. Even though I had some good girlfriends in Shanghai, I was still so far away from home. So I called him. He told me later that his roommates were heckling him to pick it up.

I told him I wasn’t feeling well and asked whether he could come out to talk to me. He came. During the conversation, he mentioned that his mom was rushing him to get married since he’d graduated from university. If he didn’t find a girlfriend by the new year, she would arrange a blind date for him, which he also hated. So I said, “What about me as your girlfriend?”—like, jokingly, not in a very serious way. He said, “No way.” So I could only say I was kidding. By the end, I don’t know where I got the courage to ask him to hug me. An innocent, light hug. And he did. After that we returned separately, but he thought, Now that I hugged her, I need to be responsible.

I was working as a front-line operator. The phone calls I took covered almost every kind of customer problem. Everybody was given the same mirror. They were all provided by the company to help us remind ourselves to serve every customer with a smile. Every day when I woke up and looked into the mirror, I was already giving myself a smile. Occasionally I would look into the mirror on my desk, and I cleaned the mirror every day.

Since I’ve worked at warehouses before, I’m familiar with logistics problems. I remember one time I had a customer from Shanghai who bought milk powder at JD. Usually we have a one-day delivery promise for customers in Shanghai, but we ran out of stock for that particular product and transferred it from the Beijing warehouse. The customer called and threatened to file a complaint, saying the milk powder for her baby had run out at home and the baby would starve if it didn’t arrive that day. I told her I completely understood her position, being a mom myself. I contacted the person in charge of the warehouse to finalize the estimated arrival time and asked him to call me once it came. That afternoon, the package arrived.

JD had this recruitment going on for group leaders. In 2013 the Sunshine Angel Team was established as a special group consisting of physically disabled people. I started to lead the Sunshine Angel Team. I had no experience leading a team before. The moment I saw them, I was shocked. The image of many physically disabled people gathering was hard to forget. I felt a certain pressure, because I didn’t know how to lead the team and train them to become professional operators. But I was determined to train them well.

Some of them didn’t even know how to use a computer, so I had to teach them bit by bit. What I did was stand behind them, telling them they could do it, giving them all kinds of Loving Encouragement. Some only had one hand available, but that was OK. I would pick the easiest article for him to practice typing. And we often say, “Clumsy birds need to take off first.” Sometimes it’s not convenient for team members who use wheelchairs to go to a team-building activity. I would tell them I could drive them there. And when we got there, I would carry them on my back to enter the restaurant. I found out that they never thought of themselves as lesser than others and always strived to exceed.

My current salary allows me to have an upper-middle-class standard of living in Suqian. In 2015 I bought a house for the purpose of bringing my son here from Xuzhou. In the same year I also replaced my car with an SUV. I never thought I would be able to own an SUV and a house at the age of 32. My dream was to live happily in the same city with my husband and children. My husband came in 2015.

Since we were little, my mom was always telling us to study hard for a better future than being farmers. One thing she often said to us was that, even if it’s just to show people you can do it, you should try to live a better life. If my mom were still alive, I believe she would say, “I’m very proud of you and feel relieved to have a brilliant daughter like you.”

Edited by Jeremy Keehn

Photo editor Aeriel Brown

Photo editor Caroline Tompkins

Charts by Dorothy Gambrell

Magazine design Chris Nosenzo

Web producer Thomas Houston

Web design Steph Davidson

With help from James Singleton and Paul Murray

© 2019 Bloomberg L.P. All Rights Reserved